From the 16th century onwards, the European colonial powers made a significant cultural impact on many aspects of Sri Lankan culture. Modern Sinhala was influenced immensely by its contact with three European languages, the languages of the colonisers: Portuguese, Dutch, and English. Prior to the Colonial invasions, Ceylon’s strategic location at the southernmost part of the sea routes that connected Asia with the Mediterranean Sea brought in many Arab, Persian, and Indian sailors and merchants. They left an indelible cultural imprint on the country by changing the social, cultural, political, economic, and linguistic outlooks of the country.

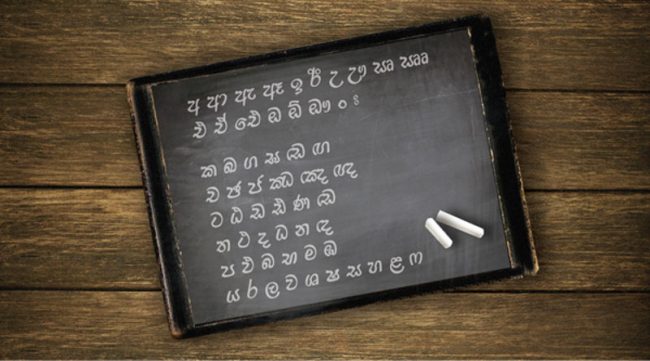

Abraham Mendis Gunasekara, in his Comprehensive Grammar of the Sinhalese Language (1891) enumerates approximately 400 loan words from Tamil, 231 from Portuguese, 112 from Dutch, and 76 from English. Sannasgala (1976: p. 87) stated that most of the Sinhala words derived from foreign sources were either Portuguese, Dutch, English, Malay/Javanese, Tamil, or Arabic.

Sinhala belongs to the larger umbrella Proto-Indo-European language group, which includes languages of the West like Greek, Latin, German, French, English, Lithuanian, and Russian. The Proto-Indo-European parent group branches off into Indo-Aryan, which includes Sanskrit, Pāli, Hindi, Bengali and, of course, Sinhala. The Indo-Aryan language group arose due to the migration of Indo-Aryan speakers from India, as early as 5 BC. Over the centuries, Sinhala has undergone significant phonetic and semantic changes. Since the Sinhala language is a member of the Indo-Aryan family, it is not difficult to connect its vocables with cognate Indo-European forms.

The Sinhala language as we know it today has evolved through four different eras. Image courtesy exploresrilanka.lk

The evolution of Sinhala can be divided into four eras (Geiger, 1938) :

- Sinhala Prakrit (200 BC to 4th century to 5th century AD)

- Proto-Sinhala (4-5 AD to 8 AD)

- Medieval Sinhala (8-13 AD)

- Modern Sinhala (13-20 AD)

Modern Sinhala (13-20 AD)

The modern Sinhala language contains many Portuguese and Dutch terms. It is believed that many Portuguese loans would have entered Sinhala after the departure of the Portuguese from the island in 1658. The Portuguese, unlike the later Dutch and British, integrated well with the locals. They intermarried with the daughters of the land and birthed a new language, Sri Lankan Portuguese Creole, which flourished as a lingua franca in the island for over three and a half centuries.

The Dutch language has also influenced Sinhala considerably in the fields of law, administration, and commerce. This is not surprising, considering the fact that it was the Dutch who introduced the Roman Dutch Law, which survives today as the general law of the land. P.B Sannasgala has cited numerous Dutch loans pertaining not only to legal, administrative, and mercantile matters, but also to food, drinks, clothing, and personal ornamentation, games, household goods, and utensils, etc.

This article seeks to dig a little deeper into the linguistic affinity between Sinhala and other foreign languages by exploring the etymological origins of many loan words borrowed from Portuguese, Dutch, and English. [Sources: Tagus to Taprobane: Portuguese Impact on the Socio-culture of Sri Lanka from 1505 AD by Shihan de Silva Jayasuriya, and Zeylanica: A Study of the Peoples and Languages of Sri Lanka by Asiff Hussein.]

Casados

Portuguese attire as depicted in the drama Gajaman Puwatha. Image courtesy anuruddhal.wix.com

The Portuguese kings banned women from accompanying navigators to the colonies. This naturally led to intermarriage with the indigenous women of the land. Portuguese ‘casados’ were the married soldiers (soldados in Portuguese) who were permanent residents of Ceylon. The Casados and Topazes (children from Portuguese native marriages) were not part of the regular army. They were only expected to take up arms in defence of their homes or during a major emergency. However, they sometimes volunteered for particular military operations. The Sinhala verb kasada bandinava comes from the Portuguese past participle casado meaning ‘married’. The Portuguese doucasado was corrupted into dikkasada, Sinhala for divorced.

Parangi Names And Titles

Princess Dona Catherina is welcomed in Kandy. Image courtesy wikipedia.org

As a result of Portuguese intermarriages with the local women, Portuguese surnames and personal names were introduced to Sri Lanka. Many Sri Lankans have Parangi (from ‘Farangi’ meaning ‘foreigner’) surnames like Abrew (Abreu), Almeda (Almeida), Aponso (Afonso), De Mel (Melo), Perera (Pereira), Ruberu (Ribeiro) etc. These people could be descendants of the Portuguese or of those converted to Roman Catholicism who acquired Portuguese names at baptism.

The Sinhalese also had several titles for men and women which were used according to the age, rank and qualities of the person (Knox, 1681 : p. 291). The Portuguese introduced new titles to Sri Lanka. The title of Dom (i.e Sir) and Dona (i.e lady) were bestowed upon chieftains and their wives who converted to Christianity at baptism. Dom and Dona are used as prefixes to personal names. For example, Dona Katarina and Dom Juan. Dona Catherina (also known as Kusumasana Devi) was Queen of Kandy in the sixteenth century who later became the Queen Consort to King Wimaladharmasuriya I after the defeat of King Rajasinhe I. Gajaman Nona was a famous Sri Lankan poet who lived in the south of the country around the time the Dutch rule ended and early British rule began. She was baptised Dona Isabella Koraneliya Perumal. Sri Lankans added Dom or Dona to their names at baptism, to signal their pre-eminence.

Do you remember the famous song by the Gypsies from the late 90s, “Signore” ? The term ‘Senhor’ (lord or gentleman) became ‘Sinno’ in Sinhala and it is used even today in the rural areas of Sri Lanka. The feminine equivalent, Segnora, however, is not used. Instead, Nona is used for younger ladies and nona mahaththaya for older ladies in aristocratic families. According to Nell (1888), even 100 years ago, Sinno (derived from Senhor) was used to address Portuguese-speaking men who wore western clothes and Nona was used to address European and burgher (Eurasian) ladies.

Portuguese And Dutch Influences On Cities And Street Names

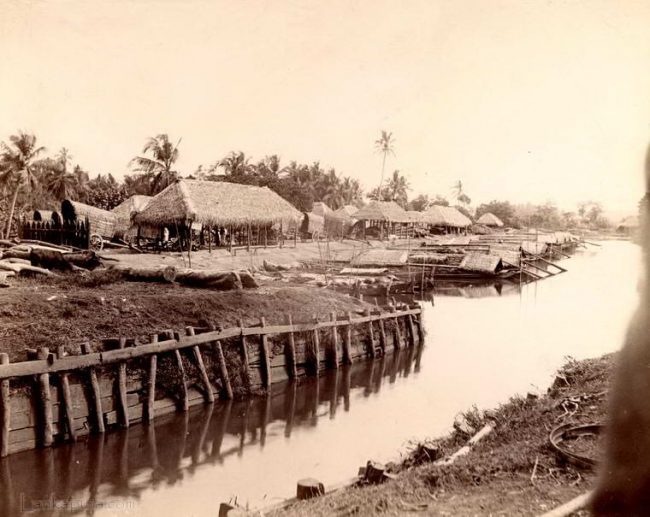

Canal View at Grand-Pass. Image courtesy lankapura.com

Many town and street names used today also find their origins in either the Dutch or Portuguese languages, some examples being:

Gal Bokka (from ‘Galio Boca’, or ‘Galle Buck’)

Santumpitiya (from ‘Sao Tome’, ‘Saint Thomas’), now Gintupitiya

Grandpass (from ‘Grando Passo’) ‒ In the book Changing Face of Colombo by R.L Brohier, there is an interesting story which explains the origin of the name Grandpass:

“As in the long years of hitherto past, at that period too the Kelani Ganga, which sweeps round north Colombo to roll its waters into the sea was unabridged. The river was at no season of the year fordable and there were two points where ferries were established. The Portuguese bestowed the connotation “Passo Grande” (present Grand-Pass) to the crossing at Nakalagam. The second crossing was called Pasbetal, literally pass of the boats, was not far from Grand-Pass, but neared the mouth of the river.”

Milagiriya (from ‘milagres’, meaning ‘miracles’) (Hettiarachchi, 1965)

Bloemendahl (Vale of Flowers) – In the enclave of the Kelani Ganga and off its left bank, which lay north of the Cinnamon plantation, there were extensive areas of grass fields and swampy land which extend southwards from Bloemendahl. Most of it was once owned by a Hollander, and named after him : “Vender Meyden’s Polder” (Pasture lands reclaimed from the marshes). The name still remains in old deeds to recall the fact that it was in Dutch times drained and used as a model farm.

The language of the colonisers lent their influence to other aspects of Sri Lankan life, too, such as:

Job Titles And Trades

Minindoruva ‒ Port. medidor, meaning ‘surveyor’

Sapateruva ‒ Port. sapaeteiro, meaning ‘shoemaker’ (Port. Sapato ‒ sapattuva, ‘shoe’)

Alugosuva ‒ Port. algoz, for ‘hangman’ or ‘public executioner’

Pederēruva ‒ Port. pedreiro, ‘mason bās’ (Dut. baas)

Tolka mudalali ‒ Dut. tolk, ‘interpreter’

Judicial Administration

Sitasiya ‒ Dut. citacio, ‘citation/court summons’

Kondesiya ‒ Dut. condicao, ‘conditions’

Notasiya ‒ Dut. noticia, ‘notice’

Perakadoru ‒ Dut. procurador, ‘proctor’

Clothing

Beeralu weaving. Image courtesy: serendib.btoptions.lk

Jeththukara is an adjective in Sinhala that is used to describe something fancy or fashionable. Jeito in Portuguese means ‘fashion’. As Sri Lankan women married Portuguese men, they adopted the Portuguese style of dress. Their sense of fashion was a hybrid of European origin. We could assume that the conversion to Roman Catholicism might have provided an impetus in Sri Lankans to emulate Portuguese clothes. The Portuguese influence on Sri Lankan attire can be traced through the modern Sinhala lexicon.

Beeralu is a lace-making craft that is still practiced in Southern Province of Sri Lanka. Pillow Lace or Beeralu derives from the Portuguese word bilro (bobbin). The wig/false hair worn by Portuguese women was called cabelleira, havariya in Sinhala. Other attire-related words that find their origins in the Portuguese language include:

- Avana ‒ (Port. abano, ‘fan’ )

- Piyara ‒ (Port. poeira, ‘powder’)

- Calesama ‒ (Port. calcao, ‘trouser’)

- Bastama ‒ (Port. bastao, ‘walking stick’)

There are also borrowings from Portuguese describing Sri Lankan jewellery, and terms associated with sewing and cutting, such as:

- Arungal ‒ (Port. argolinha, ‘ear-ring’)

- Bottam Kasiya ‒ (Port. kasa de botão, ‘button-hole’)

- Pathorama ‒ (Port. padrao, ‘pattern’)

- Mosataraya ‒ (Port. mostra, ‘design’)

- Lensuva ‒ (Port. lenco, ‘handkerchief’)

- Alpenetiya ‒ (Port. alfenete, ‘pin’)

Vegetation And Cuisine

Yes, even kaju is a word we owe to the Portuguese. Image courtesy: iStock

In many ways, it was the Portuguese who transformed the island into the tropical paradise that Sri Lanka is often described to be. They introduced plants to their colonies during their voyages by transplanting fruits and vegetables from one continent to another: oranges, pineapples, maize, manioc, and tobacco are good examples of this. In 1658, the Portuguese were ousted by the Dutch, who subsequently colonised the coastal regions of Sri Lanka. They were amazed by the variety of vegetation in the island at that time. Among the everyday Sri Lankan food names that were influenced by the Portuguese are:

- Kaju – (Port. caju, cashew)

- Anoda – (Port. anona, custard apple)

- Masan –(Port. maça, apple)

- Manyokka – (Port. mandioca/tapioca, cassava)

- Sidaran – (Port. sidrao, citron)

- Artapal – (Dut. aard-appel, earth apple)

- Pipinna – (Port. pepino, cucumber)

The Portuguese also introduced many recipes into Sri Lankan cuisine. Even the word kussiya (kitchen) comes from the Portuguese word cozinho.

The Portuguese ‘pudim’ is an egg custard with sauce (Wright, 1969). However, in contemporary Sri Lanka, pudim is a general term that embraces a variety of desserts.

Doce means ‘sweet’ or ‘candy’ in Portuguese. The sugar-glazed melon candy, aka puhul dosi, is a Sri Lankan delicacy loved by nearly everyone.

In Old Portuguese, bread was known as pan. Other food and food-related words influenced by Portuguese include:

- Peththa ‒ (Port. fatio, ‘slice’)

- Forno ‒ (Port. forno, ‘oven’)

- Paralu (Paan) ‒ (Port. farelo, ‘wheat bran’)

- Keju ‒ (Port. Quiejo, ‘cake’)

- Bora (Saw Bora) ‒ (Port. Boroa, ‘semolina’)

Note: The Portuguese “g” corresponds to “k” in Sinhala, e.g. peekudu (Port. figado, ‘liver’) and vinakiri (Port. vinagre, ‘vinegar’).

Some Sri Lankan kitchen utensils also have Portuguese etyma:

- Garappuva (Port. garfo, ‘fork’)

- Guruleththuva (Port. gorgoletta, ‘earthen vessel’) ‒ the word derives from the old French gargole meaning ‘throat’ or ‘waterspout’, which is perhaps from garg-, imitative of throat sounds.

Other terms:

Good old rathinya – also a word we use thanks to colonial influence. Image courtesy dupress.com

It is no secret that Sri Lankans love their booze, and whether that was thanks to colonial influences or not is up for debate ‒ what we do know, however, is that the colonisers did lend us a few interesting words to use in relation to drinking:

- Bebadda in Sinhala means drunkard. It comes from the Portuguese word bebado. Thabaruma is a tavern/bar which comes from the Portuguese word taberna.

Other words include:

- Rathinya (Chinese firecrackers) ‒ this word is likely to have its origins in the Portuguese ratinho meaning ‘little rat’ and was probably so called due its appearance: the fuse for lighting the cracker resembles a rodent’s tail.

- Kapothi! (finished, destroyed, lost) is a Sinhala expression influenced by the Dutch word kapot meaning ‘broken’.

- Isthirikkaya (iron) comes from the Portuguese verb esticar and Dutch strikjzer meaning to ‘stretch and extend’.

- Pagawa ‒ from the Portuguese paga, meaning bribe/payment.

- The Negombo fish market (Lellama fish market) is a place where you can haggle with the fishermen. Lellama comes from the Portuguese noun Leilão meaning auction or sale. Keval karanava (to haggle) has origins of (Dutch. kibbel). Vendesiya (public auction) derives from the Portuguese word vendas (sales).

- Kakkusiya (toilet) is a word that has Dutch origins. The literal translation of the Dutch word Kak-huis is ‘excreta house’.

- It is believed that the Sinhala verb udav karanna comes from the Portuguese noun ajuda (ayudar in Spanish) meaning ‘help’.

- Lasti (getting ready/being prepared) is a Sinhala verb which could be a loan word from the Portuguese lesto meaning quick, brisk, or ready.

- Kenthiya (anger) is a corrupted word of the Portuguese adjective quente which means warm or hot.

- Ranchuva in Sinhala means ‘a group’ ‒ the American Spanish rancho is a ‘mess-room’, originally, ‘group of people who eat together’. In Portuguese, rancho bears a similar meaning (Port. rancho, ‘soldiers’ quarters’).

The language of the colonisers clearly lent their influence to pretty much all aspects of Sri Lankan lifestyles; so much so that we can safely conclude that Sri Lankans are in fact a lot more multicultural than we may have guessed.

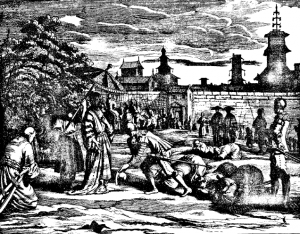

Featured image: A 17th-century painting of Dutch explorer Joris van Spilbergen meeting with King Vimaladharmasuriya in 1602. Image courtesy familypedia.wikia.com