Brought to you by Lipton Tea Room

“Under certain circumstances,” proclaims Henry James in what is considered one of the greatest opening lines in English literature, “there are few hours in life more agreeable than the hour dedicated to the ceremony known as afternoon tea.”

This sentiment, which was articulated in what is perhaps his most well-known work, The Portrait of a Lady, is one that a number of writers have, over the years, concurred with. From Jane Austen, to H. G. Wells, and even J. K. Rowling, many an author has employed tea or teatime rituals in their writing, not merely as decorative devices, but as a mechanism that aids character development and guides the plot.

At the centre of almost every social situation in Austen’s novels one finds tea. Image credit: Universal Studios/Pride and Prejudice (2005)

The beverage, which was first introduced to the British islands by Catherine of Braganza in the mid-seventeenth century, became, in the decades to come, ubiquitous in English society, and, therefore, in its literature – most notably in the writing of Victorian authors.

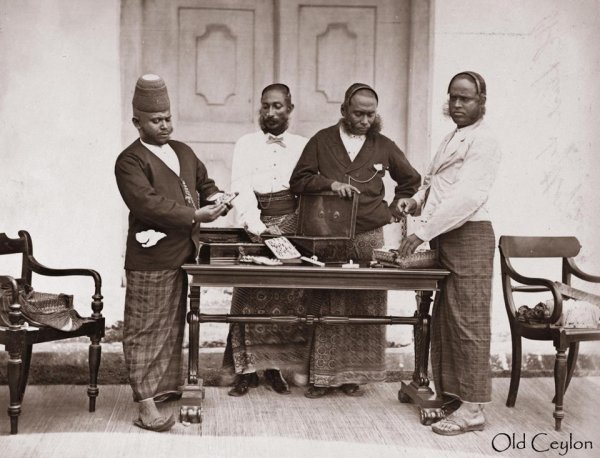

It is during the Victorian period – in 1867, to be precise – that the first commercial crop of tea was introduced to Ceylon, when the British planter, James Taylor, alongside Thomas Lipton, worked to establish the tea plantations from which a considerable portion of the tea consumed by the British in that era originated. It is, therefore, fitting that the brew has found a place at this year’s Galle Literary Festival, in the form of the Lipton Tea and Poetry Reading, which will celebrate one of the entrenched traditions in English literature – afternoon tea.

Tea And The Depiction Of The Sexes In English Literature

The tradition of afternoon tea made its way into English literature around a decade after the brew made its way into British drawing rooms in the early seventeenth century.

The brew made its literary debut in the form of tea scenes in restoration comedy, and Henry Fielding, whose body of work is largely indebted to that done by restoration playwrights, captured the function of tea in that literary period in an epigram, saying “love and scandal are the best sweeteners of tea”.

From there flourished a literary tradition of tea scenes, which grew alongside the cultural history of the beverage, influencing and enriching each other.

Evident in the early use of tea scenes in literature is the notion that tea was a feminine beverage, perceived – especially in comparison to the wine drunk by the menfolk – as milder, and more suitable for the fairer sex. Playwright William Congreve, in The Double Dealer, describes how the womenfolk, “at the end of the gallery, retired to their tea and scandal according to their ancient custom after dinner”.

Tea was, at first, considered a feminine beverage. Image credit: Roar.lk/Nishan Casseem

In time, however, tea began to be perceived as a social beverage that remedied the disconnect between the two sexes, and several etiquette books from the Victorian period speak of how, after formal dinner parties, ladies and gentlemen would retire to separate rooms for, respectively, their coffee and wine, only to congregate once again over tea.

It was tea, also, that accompanied the emancipation of women in the English literary tradition. Afternoon tea, an activity traditionally depicted as one practiced by women in the safety of their own homes, began, in the Victorian era, to spill out into the outside world – Nanda, the protagonist in Henry James’s The Awkward Age, strained against the fetters of social propriety by walking to a friend’s house unaccompanied for afternoon tea, thereby pioneering the way for other heroines in literature to do the same.

Tea As An Indicator Of Social Status

In the early years following its introduction to the British court, tea was a beverage indicative of wealth – it stood apart from the more common drinks due to its expensiveness and exoticism, and was adopted by the aristocracy as their own until, in the mid-eighteenth century, the lower classes could afford to consume it.

With the brew’s widespread popularity came another literary function – tea, now an established social norm, was employed by writers, increasingly, as a device through which characters, their behaviour, social standing, and relationships with each other were examined.

The popularity of afternoon tea in English society allowed writers to use it and its rituals as an indicator of social status. Image credit: Twinings

H.G. Wells, in his naturalistic work, Kipps: The Life of a Simple Soul, utilised teatime rituals to illustrate the title character’s want of etiquette and manners, which was indicative of his inferior social status:

He discovered Miss Coote was asking him whether he took milk and sugar. “I don’t mind,” said Kipps. “Jest as you like.” Coote became active handing tea and bread-and-butter. It was thinly cut, and the bread was rather new, and the half of the slice that Kipps took fell upon the floor. He had been holding it by the edge, for he was not used to this migratory method of taking tea without plates or table.

Tea’s Grandest Literary Moments

The significance of tea in the English literary tradition can be measured by the number of iconic novels in which the brew is featured.

The profusion of tea scenes in Jane Austen’s fiction was so great that it even inspired a book on the subject, in which Kim Wilson comments, “At the center of almost every social situation in her novels one finds tea”.

Austen’s novels contain a profusion of tea scenes. Image credit: Roar.lk/Nishan Casseem

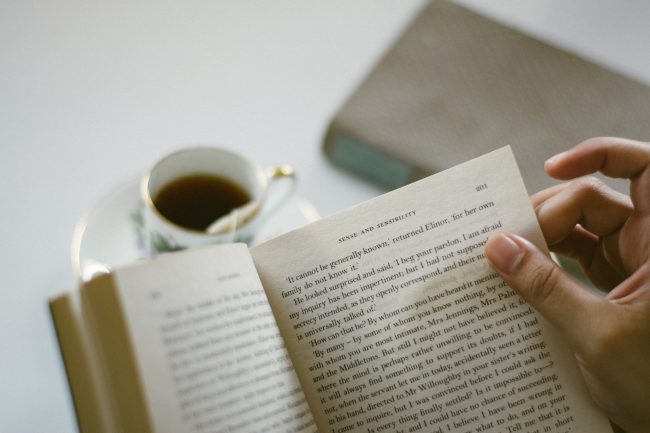

A great example of this is the famous scene in Sense and Sensibility, where, during afternoon tea, Marianne notices the ring on Edward’s finger that hints at the plot twist to come:

Marianne remained thoughtfully silent, till a new object suddenly engaged her attention. She was sitting by Edward, and in taking his tea from Mrs. Dashwood, his hand passed so directly before her, as to make a ring, with a plait of hair in the centre, very conspicuous on one of his fingers.

“I never saw you wear a ring before, Edward,” she cried. “Is that Fanny’s hair? I remember her promising to give you some. But I should have thought her hair had been darker.”

Marianne spoke inconsiderately what she really felt—but when she saw how much she had pained Edward, her own vexation at her want of thought could not be surpassed by his. He coloured very deeply, and giving a momentary glance at Elinor, replied, “Yes; it is my sister’s hair. The setting always casts a different shade on it, you know.”

Perhaps the most famous tea party in English literature, however, is that hosted by The Mad Hatter in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.

In a host of tea scenes in which order, if not present, was at least expected, the Mad Hatter’s complete disregard for the rituals and proprieties associated with the tea table was an enchanting – and welcome – change.

Literature’s most famous – and strangest – tea party. Image credit: Getty/John Tenniel

What is perhaps most impressive about this particular scene is its subtle attack on the idle tea-table chatter characteristic of the Victorian period in which the book was written:

“Take some more tea,” the March Hare said to Alice, very earnestly.

“I’ve had nothing yet,” Alice replied in an offended tone, “so I can’t take more.”

“You mean you can’t take less,” said the Hatter. “It’s very easy to take more than nothing.”

A tea scene with which our readers may be more familiar is that in J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, where Professor Trelawney, during Harry’s first Divination lesson, reads the tea leaves in his cup in an attempt to divine the future, thereby setting in motion a series of misunderstandings that shape the plot:

She lowered her huge eyes to Harry’s cup again and continued to turn it.

‘The club… an attack. Dear, dear, this is not a happy cup…’

‘I thought that was a bowler hat,’ said Ron sheepishly.

‘The skull … danger in your path, my dear …’

Everyone was staring, transfixed at Professor Trelawney, who gave the cup a final turn, gasped, and then screamed.

Professor Trelawney (mis)reading the tea leaves in Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. Image credit: Warner Bros.

In the years since its introduction to the British islands, tea has grown to become as much a part of English literature as of the daily lives of the English, and the significance of Ceylon tea in the creation of this grand literary tradition is one that cannot be downplayed.

It is, therefore, apt that the Lipton Tea and Poetry Reading – taking place at the Galle Literary Festival over the next few days – looks to celebrate this tradition, through the tried and tested combination of literature accompanied by a piping hot cup of tea.

This article was brought to you by:

Featured illustration credit: Roar.lk/Kyle Sampath Valentine