Intrigued by the stories of Jaffna food, travel writer Sachin Bhandary makes a trip to the North in search of the true cuisine of the peninsula.

It was close to nine at night when the old and tired Uttara Devi pulled into the shiny new Jaffna railway station. We were late at least by a couple of hours. As is the case with trains in Sri Lanka, the delay was not unexpected. It was my second arrival in Jaffna, but I felt no more comfortable than the first time I got off the air-conditioned intercity express a couple of years ago. Jaffna is one of the few towns which has the ability to put me at unease, and for no apparent reason. It is not troubled any more, or unsafe. But the melancholy of Jaffna makes me long for something I am yet to comprehend.

A well-meaning young friend from Colombo had once instructed me, “machang, be careful, it is Jaffna, not Colombo”. At first I found it hilarious that he would say that about a city which is just 400 km north of his own. But only after travelling and understanding the country better did I really appreciate this concern.

A generation of Sri Lankans has grown up thinking of Jaffna as a distant place. A place their army had managed to liberate in the ’90s but barely managed to keep it that way through the rest of the three-decade long civil conflict. And although the conflict ended in 2009, the physical distance between Colombo and Jaffna continues to feel a lot more than it actually is.

Crab curry is considered a Jaffna specialty.

This distance plays out in another interesting way: food. It was the internet that brought this to my notice. While yearning to know more about the pearl island, temptation led the way and I found myself drooling over the famous curries and sambols. And while most dishes seemed consistent across the island, it was Jaffna that stood out. It almost seemed as if food from Jaffna was an import even within the island. The name Jaffna was often and widely stamped, take for instance Jaffa crab curry or the soup Jaffna Kool. It was probably a mark of allegiance or even authenticity. It was clear, then, that food would be an important part of my trip to Jaffna.

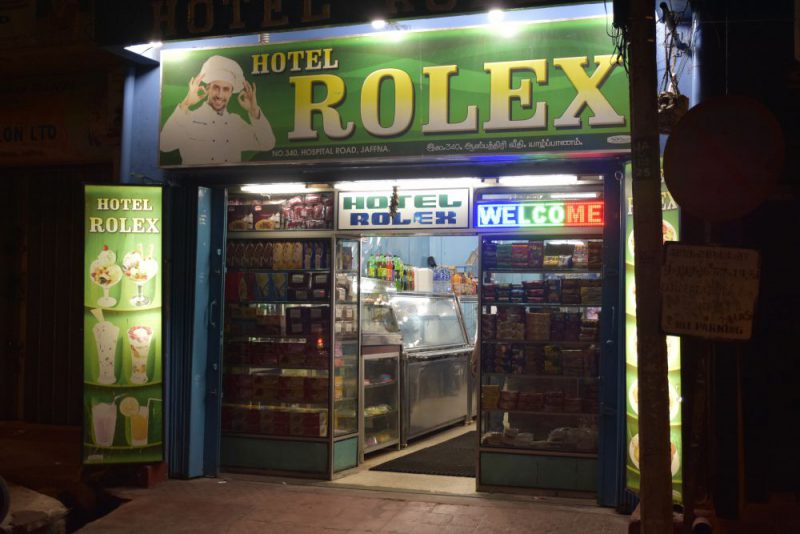

Nine p.m. is not late in most towns around the world, but for a place still trying to shake off the curfew culture from its memory, it can be. We got off the Uttara Devi and headed straight to Hotel Rolex, which had earned itself a good reputation on the internet. A famous food blogger based in South Asia had called it the ‘pick of restaurants in Jaffna’, and another Colombo website had spoken highly of its spicy Jaffna food.

The food was cold, but I decided to give it a go anyway. That they were offering ‘Rice and Curry’ was the first red flag that this wasn’t really a quintessential Jaffna eatery. We asked for cuttlefish and prawns which were made devilled style, which is also a southern favourite.

Hotel Rolex, a popular eatery in Jaffna.

Trying to stay optimistic, I told myself that we’d probably just arrived too late to sample the ‘authentic’ Jaffna dishes. The first evening was, nevertheless, a letdown in what was my ‘culinary Jaffna’ mission.

The only two things that made Hotel Rolex’s food different from elsewhere on the island was the sweat-inducing spice, which I would soon come to identify with Jaffna, and the brinjal or eggplant moju, which provided the local touch in the otherwise regular Sri-Lankan offering of ‘Rice and Curry’.

Next morning for breakfast, I found myself at Akshatai, a chain of restaurants which prides itself on being a ‘pure veg treat’. The idlis, dosais and vadais could have been straight out of Saravana Bhavan or Sangeetha Veg Restaurant in Chennai. And despite my best efforts, I could not spot anything Jaffna-esque about any of the dishes.

The idea of a strong local cuisine in Jaffna was proving to be a myth. The dishes I had read about were nowhere to be seen on the menus.

Zameen Saleem, Colombo resident and a friend, was probably right when he said, “It is not easy to find Jaffna cuisine in the restaurants of Jaffna. They cater to either domestic tourists from the South, or Indian Tamils who come for a visit.”

Even lunch at Hotel Rolex was disappointing, though in terms of taste it was quite good. The Jaffna crab curry that I was dreaming of, however, seemed to remain just that: a dream. Enquiries at a few more local restaurants drew either a blank, or a look of surprise at the mention of the dish. It wouldn’t be until next morning that things began to change.

Chef/restaurateur Wettivelu Yajanthinan, dismissive of Jaffna restaurants, almost yelled while saying, “No one in the restaurants wants to cook Jaffna food, they all want fast food, you know. Like noodles, fried rice, or rice and curry. Jaffna food takes time, it is not fast food.”

There, then, were two reasons why Jaffna cuisine was turning out to be so elusive.

Yajanthinan was the owner and executive chef of Hotel Lux Etoiles, a boutique hotel hidden in one of Jaffna’s narrow streets. A chance conversation with a Colombo friend had led me to this place.

It was late morning when I met the eccentric chef who had his own portraits painted on the walls next to the hotel’s swimming pool. A few hours later, I was digging into what was finally an authentic Jaffna treat. The crab in the famous Jaffna crab curry was juicy and the curry itself was so fiery that it almost had me in tears. But despite the heat, the mixture of rice and the gravy was immensely satisfying.

Many Jaffna restaurants offer slightly different variants of the quintessential Lankan ‘Rice and Curry’.

But it was another dish that proved to be the more interesting find, and that was brinjal paal curry (paal meaning milk, and here referring to coconut milk). Mildly flavoured to the extent that it was almost neutral, it provided the perfect antidote to the fiery crab curry.

The meal also included other delights like beef peratal or dry beef curry, which can also be found in Tamil Nadu. Fish maruthuva, which the chef had mentioned as a medicinal dish, was heavy on the tamarind. Aniseed also made its presence felt through various dishes, and the heat of the spices was easily more than a few notches higher than anywhere else in Sri Lanka.

After the spicy lunch, our culinary mission took a sweeter turn later in the day. The next stops that hot afternoon were Jaffna’s famous ice creams parlours. For a city with almost no infrastructure for recreation, the number of the ice cream parlours spring a bit of a surprise.

Jaffna’s famous Rio ice cream parlour.

The ice cream parlours are a bit like what coffee shops are to most cities. It is here that the young and old go to take a break, chat up or just to find respite from the dry heat. Rio and Lingan may be the most famous, but they are just two of the dozen odd ice cream brands that this city boasts of. And for a city of the size of Jaffna, that’s a lot of ice-cream!

Even if diabetes is not your cup of tea, the story behind Jaffna’s hyper sweet ice creams is worth the visit. It would seem that the past conflict had found a way to make its mark on even ice cream. A friend told me that the extra sweetness in Jaffna’s ice creams comes from the use of saccharine. Sugar was difficult to come by during the war and ice cream makers turned to the alternative sweetener. And that tradition continues till date.

Nallur kovil

Rio and Lingan stand quite close to each other on Point Pedro Road not far from Nallur kovil, the most famous Hindu temple on the peninsula. Don’t be mistaken, Rio has nothing to do with its namesake Brazilian city: it stands for ‘Rathinam Industrial Organisation’. I helped myself to a ‘Rio special’ which was a mix of three ice cream flavours served along with jelly. It seemed pretty good value for LKR 100. Next, we paid a visit to Lingan ice cream down the road, which is characterised by the excessive use of green, both in its branding and interiors. A Sunday(sundae) special kept me company at this outlet that seemed to be popular among families. The generous offering had four different flavoured ice cream scoops along with jelly, fruits, and dry fruits; clearly, Jaffna has a special love for ice-creams.

The ice creams here tend to be super sweet – a result of the saccharine used.

Even if there was a way to pick between Rio or Lingan, I couldn’t. Both of them served super sweet ice creams with generous portions at pretty good value for money. Maybe Rio’s modern interiors score over Lingan’s slightly dated ones.

With this turnaround of fortunes, there was only one major thing missing from my Jaffna culinary expedition. Sri Lanka is abundant with coconuts and from the fermented sap of the palm tree comes the coconut arrack. But Jaffna is no coconut country, it is the palmyra, the other palm, that rules this peninsula. Hence, palmyra arrack is typical of the region and the coconut version is imported from down south.

My friend and I walked a dimly lit road that evening off the A9, the highway that connects Jaffna to Kandy in central Sri Lanka. A few minutes later, we were at Ravi Bar & Restaurant. With hardly any food on offer, it wasn’t quite a restaurant. Drinking palmyra arrack at a seedy local bar was my idea, and my friend clearly did not approve of being surrounded by a bunch of drunk locals. But things started to ease a bit we after we settled down with a green and yellow-labelled bottle. The amber-coloured liquid was drier compared to the sweet taste of its coconut counterpart. It’s dry, woody taste had a clear hint of the palmyra fruit. To get something to eat wasn’t easy. Only boiled eggs and peanuts were on the menu, and yes, ‘sauces’, which I later realised were chicken sausages.

In Jaffna, it’s all about the palmyra arrack.

Following Jaffna’s food trail had been interesting, to say the least. While it was difficult to find authentic Jaffna cuisine outside of the homes or the high-end restaurants, things like palmyra arrack, or even the ice creams were a lot more accessible.

As I gulped down another glass of the arrack with a local brand of sparkling water, I could not help but wonder how tricky Jaffna could be to newbies. On one side it is a melancholic town still coming to terms with the brutality of its contemporary history. But on another, it is a place marked by extremes. Spicy at times, and super sweet at other times.

Realising that I was not a Sri Lankan, a tipsy gentleman came up to me at Ravi Bar and said, “Jaffna is the city is the heart of love!”

If there was some rice and Jaffna crab curry, I would most definitely agree.

All images courtesy Diren Dantanarayana