It was 2:30 a.m., in rural Anuradhapura, when M. Dharmasena woke to the sound of his wife’s piercing screams. Before he could react, a deafening roar of brick and glass drowned her out, as a young male elephant bulldozed the side of his house.

The elderly farmer, along with his wife and two children, was lucky to escape unscathed. But the encounter left their house destroyed, and to make matters worse, the last of their paddy harvest was gone ‒ swiftly devoured by the hungry elephant.

Dharmasena’s house, rebuilt after the elephant attack. Many farmers store paddy inside their houses, but conservationists say that this is an invitation for hungry elephants. Image credit: Roar/Christian Hutter

Since the encounter in October last year, prevailing drought conditions have made it impossible to plant more paddy. Dharmasena has had little choice but to bury himself in debt to repair the damages to his home ‒ the total bill coming up to over Rs. 300,000.

Meanwhile, his daughter Ramani, demands to know why government authorities, and the Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC) in particular, have not provided support. “We were visited by officers from both the wildlife department and the police. They came here, took photos, asked questions, and left without helping us at all,” she said.

According to officials at the DWC, human victims of the Human-Elephant Conflict (HEC) are entitled to Rs. 100,000 in case of property damage, Rs. 75,000 in case of injury and, as of last month, Rs. 500,000 to family members in case of death.

Until recently, complaints related to the HEC had to be delivered directly to the DWC central office in Colombo ‒ meaning an application could take up to two months to process. Since September last year, however, District Secretariats have been given the power to process complaints, so as to expedite the process to around a month.

Despite these stated provisions, officials at the DWC were unable to explain why Dharmasena’s complaint has taken so long to be processed.

Unfair Burden

Sri Lankan volunteers and wildlife officials try to restrain a wild elephant believed responsible for the deaths of two people in Anuradhapura, in November, 2014, Image credit: AFP/Athula Bandara (AFP)

While the DWC often comes under fire for not being able to provide adequate protection or timely compensation to victims of the HEC, many environmentalists are quick to jump to its defence. Some even question whether the responsibility to protect the human side of the conflict should fall on the DWC at all.

Chairman of the Centre for Conservation and Research ‒ Sri Lanka, Dr. Prithiviraj Fernando, argues that, “When we talk of the HEC, we only look at half the story. What we mean is the impact that elephants have on people. And what we do ‒ putting up electric fences, translocating elephants, and providing monetary compensation ‒ is for the benefit of people.”

According to Fernando, this line of thinking has lead governments throughout Asia to place the burden of protecting the interests of rural farming communities squarely on the shoulders of the underfunded and understaffed conservation sector, rather than other relevant authorities.

In the Sri Lankan context, this has meant that the DWC is the defacto government agency that victims look to for protection and compensation. The result is that the DWC is forced to allocate a significant portion of its meagre funds to rebuild houses and implement electric fences around villages, rather than directly tending to its mission to “ensure conservation and wildlife heritage”.

For perspective, there are roughly between 5,000 to 6,000 wild elephants roaming around Sri Lanka ‒ nearly all of which inhabit the dry zone. Many of these elephants are not contained within protected areas, and the few that are, face difficulties due to illegal human encroachment and deforestation.

As Fernando puts it, this means that at any given time, “There are millions of people, and thousands of acres of land where humans and elephants coexist. The scale is such that, to expect around 1,300 DWC officers to adequately prevent and manage the HEC is a pipedream.

“The burden of securing villages against wild elephant attacks, and defending against crop damage, should be shared with agencies like the the Agriculture Department, Irrigation Department, or even the Disaster Management Centre,” says Fernando.

Natural Disaster

Deforestation and human encroachment are believed to have aggravated the human-elephant conflict. Image courtesy wikimedia.org

Ignoring the human aspect of the HEC is not an option, of course. The fact remains that many of the human victims belong to Sri Lanka’s vulnerable farming communities, who themselves have socio-economic struggles and little access to the education or resources needed to prevent the HEC.

One government agency that shows a willingness to take over or supplement the DWC’s role in tending to the human side of the HEC is the Disaster Management Centre (DMC). Established through the Disaster Management Act in 2005, the state agency has since played a leading role in ensuring disaster readiness and relief to victims of floods, landslides, and other natural disasters.

When questioned about the DMC’s stance on the HEC, DMC Director General G. L. S. Senadeera said that, elephant encounters, particularly those that lead to loss of human life or property, could very well be classified as a natural disaster, and thus fall under the purview of the DMC.

But the question of providing compensation and protection is more complicated. Says Senadeera, “We recognise the HEC is a natural disaster problem, but we currently do not have funds to support victims or prevent occurrence. We have requested for funds from the National Insurance Trust Fund to begin work on this. In the meantime, we are happy to work with the DWC.”

DWC Deputy Director of Elephant Conservation, U. L. Thaufeek, tells Roar that discussions have already taken place between the DWC and the DMC.

“Last year, we formulated a programme for disaster prevention in conjunction with the DMC. We identified 16 ‘corridors’ that connect elephant habitats, and plan to discuss relocating some of the people who live in these areas. This could prevent a huge amount of HEC incidents,” explained Thaufeek.

Says Thaufeek, “Other agencies should take responsibility in dealing with the HEC issue and work with us on a broad level. We have expressed this view to other government agencies but had little success in gaining support. People continue to feel that the HEC is a DWC problem alone and that it is our responsibility to provide support.”

Beyond HEC

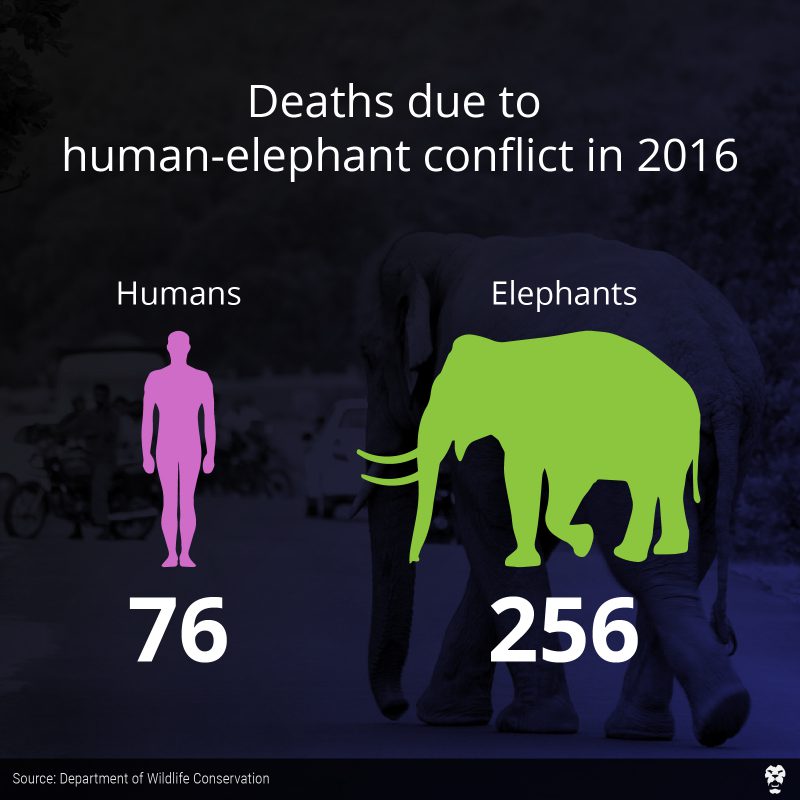

Last year alone the HEC resulted in the deaths of 76 humans and 256 elephants, according to statistics from the DWC. But what these statistics don’t show is the broader ecological struggle taking place in post-war Sri Lanka.

“The concept of the HEC is too narrow,” says environmental lawyer Jagath Gunawardana. “We need to look at this issue holistically. Elephants’ ability to fight back, their intelligence, and cultural significance, has given them a media spotlight. But thousands of other species come into conflict with humans daily and their deaths are less reported.”

For Gunawardana, the problem is one of increasing deforestation and disregard to the welfare of native wildlife. The solution, therefore, is to increase the capacity of the DWC while reducing its burden to cater to the interests of human settlements and agricultural lands.

“The DWC’s ability to act independently should be strengthened,” says Gunawardana, adding that, “For the past year and a half, lateral interference from agencies like the Mahaweli Authority and the Board of Investment has lead to the loss of forest land for development projects.”

With construction and development still booming in the post-war era, Sri Lanka straddles the dual responsibility of uplifting its rural poor, while nurturing native wildlife. Success may require a more equitable distribution of responsibilities between government agencies, and a holistic approach to sustainable development.

Featured image courtesy sundaytimes.lk