On 22 July, President Ranil Wickremesinghe, on just his second day as President, oversaw a pre-dawn police and military raid on #GotaGoGama, the anti-government protest site at Galle Face. In a grainy video from the raid, a man dressed in jeans, a grey t-shirt and a grey hat is cornered by a group of six troops in helmets and vests, holding batons. One of them shoves him, pushing him into a waiting line of troops while bystanders shout out their objections. The man disappears behind a line of barricades.

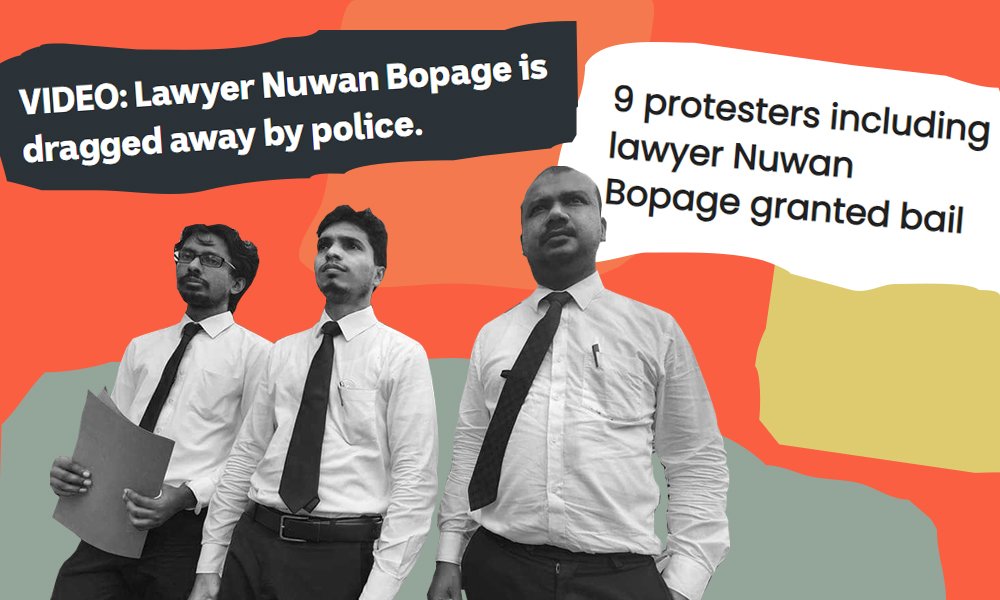

Soon after being dragged into and surrounded by armed men in uniform, human rights lawyer Nuwan Bopage was arrested, along with 8 other people. He was granted bail later that morning, when a large group of lawyers, including the President of the Bar Association of Sri Lanka (BASL), Saliya Pieris, appeared at the Colombo Magistrate’s Court to represent him.

“It’s a normal thing in my life,” Bopage told me, referring to getting arrested. From the beginning of the protests in March this year, he and a number of other lawyers showed up in shifts at Galle Face and other protest sites, offering free legal representation to arrested protesters and mediating between civilians and the police. And so, when the movement was crushed four months later, hastily and under the cover of darkness, Bopage was there, like he always was.

Who’s Next?

Bopage once had to represent a man accused of terrorism for selling a SIM card.

“After A-Levels, the young man had started a business selling SIM cards,” Bopage said. “A person connected to the Easter bombings had purchased a SIM from him. It was only after I filed a Fundamental Rights (FR) petition that the Attorney General came before the court and said there was no evidence against him, and that he could be discharged. By that time, he had already been in prison for a year.”

This man was one of the hundreds of Muslims indiscriminately arrested and detained under the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA) in the aftermath of the Easter terror attacks in April 2019, often without any evidence. As many as 300 remain in custody without trial as of this year. Bopage has watched this same cycle play out one too many times.

“Just after the war, in 2009, there were hundreds of Tamil detainees arrested under the PTA. A majority of them remained in prison for 10 to 15 years without charges filed against them,” Bopage, who represented a number of these detainees, said. A few were freed with the help of foreign embassies and as a result of international pressure, but a few still remain indefinitely incarcerated in the Welikada Prison, he said.

“Those days, when we brought up the [issue of the PTA], the majority was not willing to accept it because most of the detainees were Tamil,” he explained further. “This changed after the Easter Attacks – a lot of Muslims had earlier supported the PTA because its victims were not Muslims, but after 2019, a majority [of PTA detainees] were Muslims.”

It wasn’t until the anti-government protests this year that much of the Sinhala majority began to pay attention to the PTA. “With the influence of the struggle and the student movement’s leadership in that struggle, Sinhala people have gradually started to question the PTA,” Bopage said, referring to three student leaders — Wasantha Mudalige, Hashan Gunathilake and Galwewa Siridhamma Thera— who remain in detainment after having been arrested under the PTA in August this year for their respective roles in the protests. “So now is the ideal time to fight against it.”

Terrorism By Any Other Name

Bopage is currently representing Mudalige, who, along with Gunathilake and Siridhammma Thera, has been issued a 90-day detention order for further questioning and interrogation by the Terrorism Investigation Division (TID), with permission from the President in his capacity as Minister of Defence. “Wasantha has been detained for more than one month now, and has only been questioned for two or three days,” Bopage said. “All the other days, he’s just lying there in his prison cell.”

Bopage faces the same issues representing Mudalige as with all his PTA cases. “It’s very difficult to get access to your client. Even when I have been given access, I do not have the freedom to talk with my clients privately. If I ask for important information for legal purposes, [officers] can interfere with that,” he said. Much of this is out of his control, as is what happens when his clients are left at the mercy of law enforcement officials — “As lawyers, whatever instructions we give [our clients] while they are in custody, the police can still mentally and physically harass them to achieve their objective,” Bopage said, explaining that police may use information overheard in a discussion between a suspect and his lawyer to threaten or intimidate the suspect, causing them to act against legal counsel. This is done, he said in order to have the suspect sign a forced confession — often under duress or threat of physical abuse, and in the case of most Tamil and Muslim detainees, written in a language they cannot read or understand.

Under any other legislation, a coerced confession would not be so damning. “Confessions generally do not have evidential value during the trial, but under the PTA, if there is a confession, the judge can consider it as evidence,” Bopage said. “During the investigation and during the trial, the role of the lawyer is narrowed by [the PTA], and therefore it’s very difficult to get justice for our clients.”

To Bopage, the PTA is both fundamentally flawed and wholly unnecessary. “During the investigation period, only police have access to the suspects, and nobody is there to check both sides, so it’s an ex parte inquiry — this violates the rules of natural justice,” he said. “And when they arrest someone under the PTA, they are coming to the conclusion that that person is a terrorist, so that’s a violation of the presumption of innocence, which is a fundamental of our law.”

System Reboot

Although he is himself a lawyer, Bopage is critical of the justice system as a whole, believing it serves the interest of a select few. “In our court system and criminal justice system, there’s no justice at all for poor, vulnerable people,” he said. “If you are rich, if you are influential, there are a lot of loopholes you can use.”

But he does not believe tackling just the judicial system is enough. “Crimes are directly connected to poverty,” he said, pointing out that legal reform alone would be superficial and unsustainable without drastic socio-economic and political reform.

The connection between economic decline and social and political instability spares very few, especially in Sri Lanka, where wealth disparity is so stark. “From the very beginning, lawyers were also victims of this economic downfall,” Bopage said. “Their main source of income is their clients. When clients don’t have a means of income, lawyers cannot survive. And one of the reasons for their involvement [in the protests] was that they are also victims of this crisis.”

The economic crisis, he continued, contributed to a sense of solidarity, uniting people from all brackets of society in a common goal against a common enemy. For lawyers in particular, this brought about a shift in public perceptions of their profession — “From the time the Mirihana incident took place [on 31 March], more than 300 lawyers from all over the country voluntarily appeared for protesters. That’s a good thing. The perception of lawyers was very dark before that.”

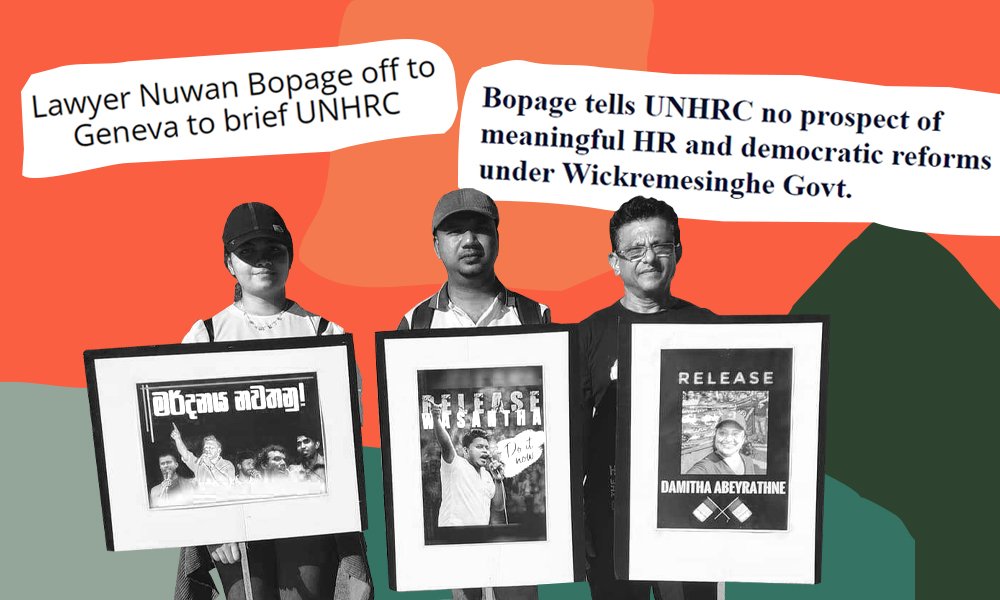

As the intimidation of protesters continues months after the raid at Galle Face, Bopage is not hopeful about the future of the country under its current government. Testifying at the 51st session of the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) in September, Bopage said there was ‘no room for any optimism about the prospects of meaningful human rights and democratic reforms and accountability under the administration of President Wickremesinghe.’

“It’s very clear that they have no solutions for the current economic crisis besides going to the IMF [International Monetary Fund],” Bopage added to Roar Media. “[And] going to the IMF means that they will send us a list of conditions like imposing more taxes, the privatisation of government institutions, and selling national assets, which the masses will not be happy about — this is inevitable. So I think there’s a possibility of another peoples’ uprising soon.”