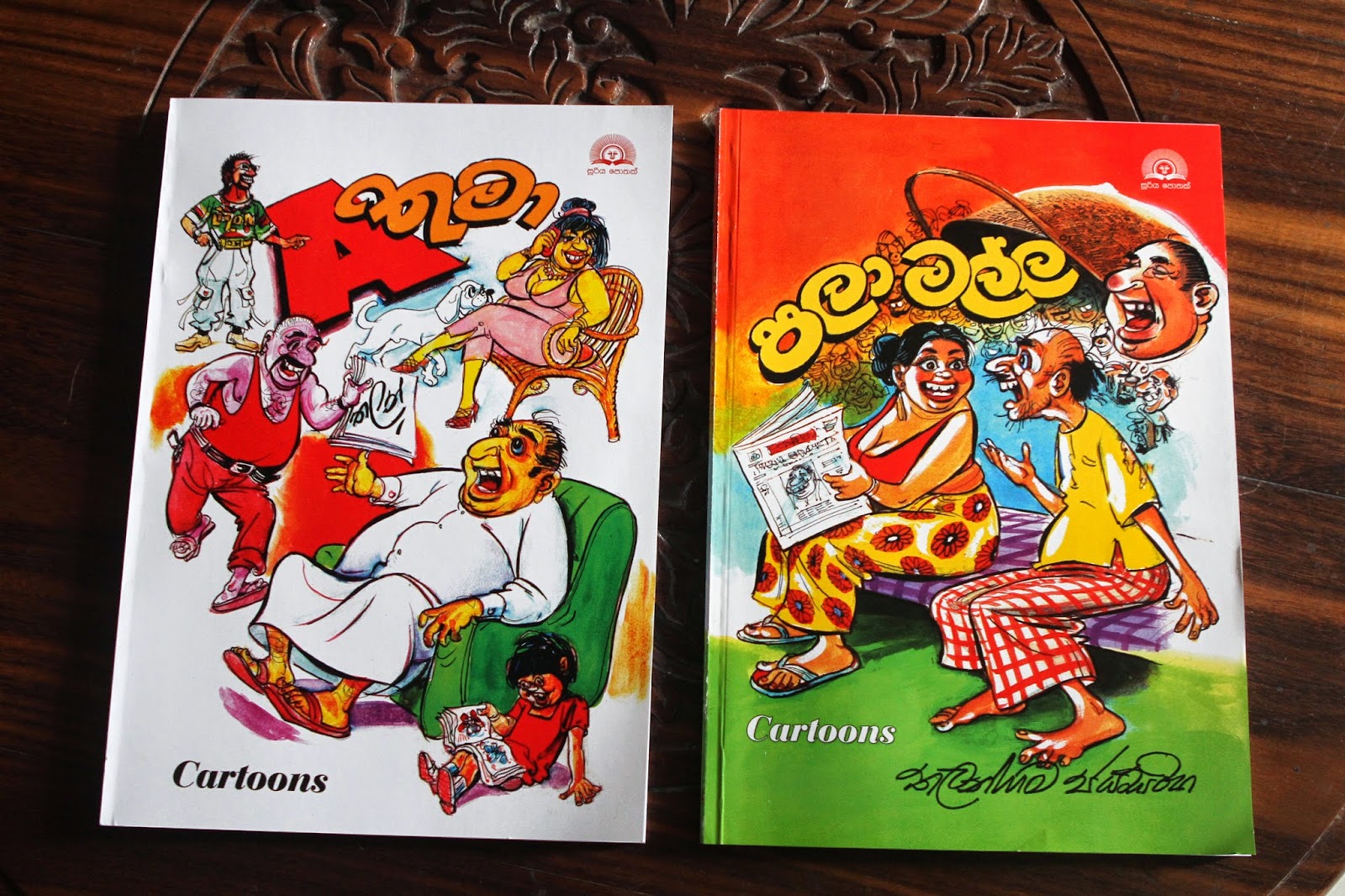

There was a time, decades ago, when comic strips were very popular in Sri Lanka. This was when there were newspaper pullouts dedicated solely to local comics or ‘chithra katha’ (literally, ‘picture-stories’), as they were known then.

Over time, the popularity of comic strips dwindled, and now exists primarily in the form of the daily political cartoon, a meme, or the work of an independent artist trying to make a name for him (or her) self.

This is something ‘Papadamn’ is trying to change.

“My original intention wasn’t to create serialised comics,” Achinthya Amarakoon (26), told Roar Media. “But people started re-uploading onto Facebook some of the random comics I published on Elakiri [a local internet forum], and I realised people liked them, and that I should perhaps upload them to Facebook myself!”

The page she created was called ‘Papadamn’, (a play on the name of a ubiquitous lunch-time offering) and started off as a hilarious, yet critical take on Sri Lankan society and politics.

Realising—with increasing popularity on social media—that there was an audience for comics, Amarakoon decided to create a serialised strip, entitled ‘Sakkai-Muniyayi’, which would tell of the exploits of a misbehaving young god, and a young demon, who have been exiled to live in present-day Sri Lanka.

As with all her other content, ‘Sakkai-Muniyayi’ is rooted in Sri Lankan folklore and ground realities, and is marked with characteristic humour. Having debuted on Facebook exactly a year ago, in July 2018, ‘Sakkai-Muniyayi’ has now successfully concluded one season, and is looking forward to publishing a second one, after a reasonable break.

“It was supposed to be a little experiment and I only drew the first five pages,” Amarakoon said. “[But] I was amazed by the reception and decided to continue.”

While ‘Sakkai-Muniyayi’ ran smoothly with few hiccups, “serialisations come with a lot of risks,” Amarakoon said, adding that she was lucky that ‘Papadamn’ already had an audience when she introduced ‘Sakkai-Muniyai’ to the world through her page.

She also realised that despite the obvious draw of social media, publishing on Facebook came with its own challenges. “I always get at least one person asking me how to navigate through pages, and [Facebook’s] algorithms can mess up with the reach from time to time,” she said.

This makes it necessary for Amarakoon to keep ‘Sakkai-Muniyayi’ and her gag-comics going simultaneously. “’Sakkai-Muniyayi’ will not go viral—it has a known audience that returns to read the comic strip,” she said. “But I have to publish a gag-comic once in a while to reach new audiences.”

While ‘Papadamn‘ is little more than a hobby at this point, it is not something that generates her an income, so Amarakoon does have to stick to her day job. “I work as a UX designer,” she said. “[But] since I work from home, I get to spend some time on my hobbies.”

Amarakoon is also excited about the way comic strips are making a comeback in Sri Lanka. “Comics are an amazing storytelling medium,” she enthused, “and people are starting to rediscover it. I never thought ‘Sakkai-Muniyai’ would get this kind of reception. But the fact that it did makes me feel really positive about where we’re headed.”

Her comic strip comes 67 years after the first Sri Lankan comic strip to be published, ‘Neela’, by artist G. S. Fernando. Published in the Sunday Lankadeepa in 1952, it told of the adventures of a vedda (indigenous Sri Lankan tribesman)—which, according to Professor Sunil Ariyaratne’s book, ‘The Development of Chithra Katha’, was clearly influenced by Edgar Rice Burrough’s ‘Tarzan.’

Fernando’s pioneering work was followed by that of the late Susil Premaratne, who created many comic strips for the local Sunday Lankadeepa, like ‘Landesi Hatana’, ‘Ran Doopatha’ and ‘Hora Hawula’. According to Kalakeerthi Thalangama Jayasinghe, (83), who is credited with being the third published comic artist in Sri Lanka, the inspiration for these could have come from Western comics such as Tarzan, Roy Rogers, Kid Carson, the ‘Eagle’ magazine and Cowboy comics, which were widely available at that time.

“In those days The Observer [also] carried a full page of cartoons and comic strips,” Thalangama Jayasinghe told Roar Media, reminiscing that characters like Tintin and Rick Kirby were very popular.

Comic artists in Sri Lanka drew inspirations from various sources, like the jataka kata from Buddhist scripture and stories inspired by Greek myths and Russian literature. Comic artists like Bandula Harischandra, (who was the first to create comic strips in colour), Janaka Ratnayake, Anura Wijewardena, Anura Srinath, and Ananda Dissanayake were among many who contributed to what is considered Sri Lanka’s ‘Golden Age of Comics.’

Jayasinghe recalled how popular comic strips were even adapted to film: ‘Saptha Kanya’, starring Kamal Addaraarachchi and Sangeetha Weeraratne, was based on a comic strip he created, while Daya Rajapaksha’s comic strips inspired 12 films, including ‘Hulawali’, in which Gamini Fonseka acted, and Malani Fonseka’s ‘Nirupamala’.

Famous novels were also adapted into comic strips—Jayasinghe himself adapted two novels by author D. B. Seneviratne. “Martin Wickremasinghe [also] asked me to adapt one of his books,” Jayasinghe said, “But for some reason, it never happened.”

These golden years of comic strips in Sri Lanka drew to a close in the 80s and the 90s, the advent of the television causing its demise, Jayasinghe said. But with the Internet and social media, comics and comic strips have new hope.

Pages like LankaComics keep the memory of past comics alive while artists like ‘Papadamn’ (which is a really a two-man show—Amarakoon ably edited and managed by her partner Rajitha Perera), and Sachi Ediriweera and Isuri Dayaratne who create Sri Lankan stories and graphic novels at an international level, ensure that the work that began with the humble ‘Neela’ will be carried on into the future.

*Special thanks to Lalith Bandara Samarakoon.