Every Friday, Benislos Thushan, a programme officer at the Office for National Unity and Reconciliation (ONUR) boards an overnight bus from Colombo to his hometown in Jaffna. He lands at dawn on Saturday and a few hours later, goes to the American Corner—the American Centre’s educational outreach branch—to conduct weekend classes on digital storytelling.

“One of the things that really excites me about coming every Saturday and Sunday to Jaffna..,” he says, “is to be with these young people who are passionate about storytelling, who want to go out, and who want to tell stories.”

Having been caught in the crosshairs of the war and growing up in a refugee camp during his early childhood, Thushan recognises vacuums that need to be filled in Jaffna — mainly concerning communication, journalism, and politics. With this in mind, he moved to Colombo a few years ago to work as a journalist, and then joined ONUR, where he works with the Communications and Economic Development Unit. More recently, he started digital storytelling classes to empower citizen journalism in the North.

‘Everyone Can Take A Selfie. What More?’

We sit in at one of the classes on a Sunday morning. A mixed group of around ten sit in a circle facing a projector, listening intently as Thushan takes them through case studies of photojournalism projects like the Humans of New York. Some of them have come prepared with story ideas of what they want to work on, and how they intend to frame it. Their stories are features, highlighting an angle of life in the North which is otherwise overlooked in mainstream media. Their pitches include stories of the challenges faced by female heads of households; the medical benefits of using utensils made of clay; and of under-preserved Tamil heritage sites in the area, to name a few.

Thushan sees social media as a good alternative to the mainstream media. Given the popularity of smartphones and the love for selfies, he recognises this as potential to engage with youth to fill the gap when it comes to substantial Tamil content.

To this end, he founded the Digital Storytelling (DST) programme in April 2016, and applied to the American Centre for a grant to run the initiative. Then, he developed a curriculum consisting of three main components, and spread the word about the course — first through social media, then word of mouth.

“DST is made up of three different parts. The first is the fundamentals of storytelling,” he tells us. “Here, we teach basic steps and concepts: like who is the storyteller, who is the audience, what are the tools necessary, and of the paradigm shift in the media. Of how the audience is now empowered and can also be participants when they see something.”

The second and third components consist of photography and social media respectively. The rationale behind this, he elaborated, was not just to equip the participants with knowledge and skills, but to also give them a platform to showcase their work. Many of the students know how to use Facebook for personal purposes, but now they learn about managing pages, captioning stories, and writing for a target audience. They are taught the same kn0w-how for Instagram.

“Photography is a natural thing. Everyone knows at least how to take a good selfie,” Thushan said, adding that the intention behind DST was to empower people to find stories worth telling from within the community, as opposed to taking photographs alone.

Preserving Stories And Culture

The students enrolled in Thushan’s storytelling classes aren’t journalists or involved in the media sector. They come from varying backgrounds, such as the corporate sector and academia, among others. But they are united by a passion for citizen journalism.

The course itself is free, but applicants are accepted only after a thorough interview,through which Thushan gauges their commitment to follow through. As a result, there haven’t been any dropouts as yet.

Many of the students see the course as an opportunity to contribute to society, and give back to their hometown.

For Aditya Ramanitharan, the DST programme provides an opportunity to pursue her interest in journalism. “I didn’t choose journalism as a career because of restrictions in my family, but I can be a citizen journalist through this,” she said. Ramanitharan is going to pursue law, but intends to continue posting online now that she knows how to interview people, approach strangers for stories, and utilise social media.

For many others, it is about highlighting issues and preserving culture.

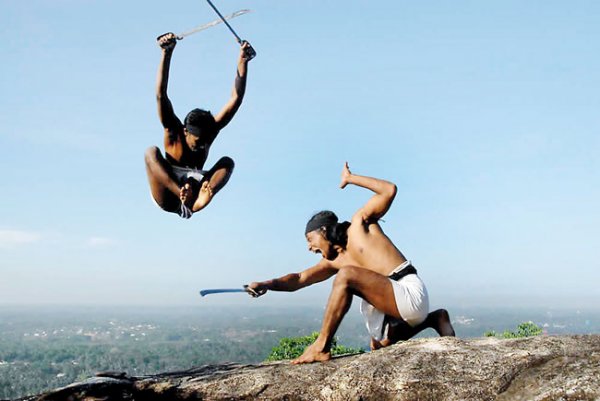

An undergraduate at the University of Jaffna, B. Kajeevan was always interested in photography. He learnt about this course through Facebook, and enrolled shortly after. Like several others in his class, he was unaware of social media platforms and how they could be used for more than just sharing memes and photos. One of the stories he is currently working on is of how heritage sites of importance to the Tamil community are being neglected as Jaffna develops.

“Take for instance, Kandarodai [a historic site of Buddhist importance]. It’s very well looked after, but others are ignored. The municipal council needs to take steps to preserve other sites of equal historic importance, but most are in disrepair,” he explained.

The Right To Write

Thushan is ecstatic about how successful the programme is so far. The students are keen to interact and learn from him, and the alumni are active — even running their own content pages now. He cites Everyday Mulaitivu and Jaffnapedia as examples of their digital storytelling successes.

We met Franka Murphy, a student from one of the previous batches, who dropped into the American Corner. She enrolled for the DST classes before her nursing course began, mostly to learn about photography. Having completed the course, she found that she had learnt a lot more — from learning how to create short videos, to presentation and delivery skills, as well as building an online portfolio.

“Most importantly, I didn’t know about citizen journalism,” she says. “I didn’t know I had the right to report on an issue as an individual, and now I know I can do that.”