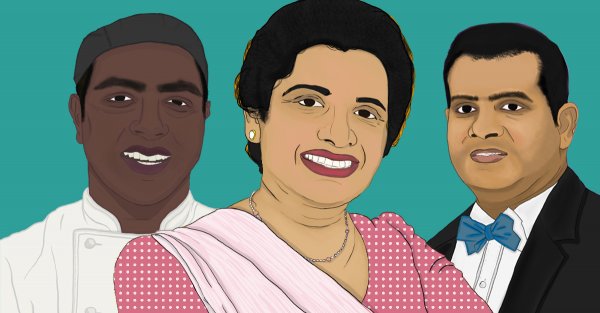

“The basic problem we face is that the Muslim male leadership has no idea of the ground realities,” says Aneetha Firthous, a Kattankudy-based activist. “Not once have they sat with a woman to talk about her problems, and the abuse and victimisation she faces.”

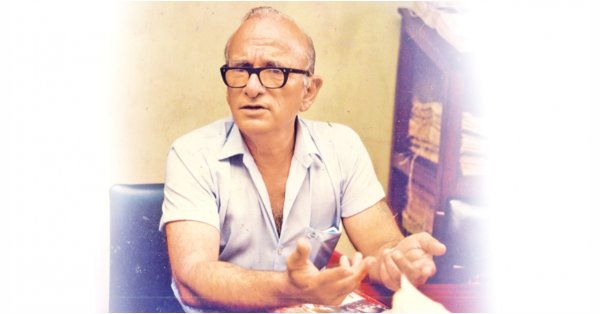

Muslim women have been campaigning for reforms within the Muslim Marriage and Divorce Act (MMDA) for decades, citing human right violations. Given mounting pressure, former Justice Minister Milinda Moragoda appointed a committee in 2009, headed by Justice Saleem Marsoof, to look into the matter. The report took nearly a decade to emerge, and was presented to the Justice Ministry only towards the tail end of January 2018.

However, the report was never officially released to the public despite numerous requests — until now. On July 18, the Ministry uploaded three extensive documents consisting of two sets of recommendations, and invited members of the public to discuss them.

The report, containing well over 300 pages, addresses polygamy, the age of marriage, marriage registration and the requirement of a guardian, and updating the status and standards of quazis, among other topics.

Processes And Timelines

Human right activists and campaigners have been calling for the report’s official release over the last six months, especially as the Ministry refused to share it, citing a ‘difference of opinion’ among the committee members.

Reply from #MOJ to my #RTI request for the #SaleemMarsoof report on #MMDA reform. If there is a “difference of opinion”, perhaps the #MoJ should just release both versions? @mplreforms @tatukorale pic.twitter.com/xAkfhZwlNL

— Mari (@Mari_deSilva) February 21, 2018

Speaking to Roar Media, human rights lawyer Ermiza Tegal stressed on the redundancy of going back and forth between the members for consensus.

“The committee has concluded its point,” she said. “The report can definitely be a starting point where there is consensus on all fronts, in order to move forward.”

The report’s publication and the Ministry’s call for public engagement has been applauded by the activists we spoke to. However, one concern remains: the process.

“How long will this be open for consultation, and when will it be presented to Parliament?” Tegal asked. Citing previous reports for reform which hit dead ends, she noted the importance of retaining public confidence, especially amongst those whom the report will directly impact.

Civil Involvement

The Muslim community is divided about many subjects, which is why public consultation and engagement is important. This is evident when issues such as deciding a minimum age of marriage are up for debate.

“For instance, why is [the age of] 16 being proposed instead of 18, when the minimum age of marriage for everyone else in the country is 18?” Tegal asked. “What’s the logic or benefit behind this? They [the 16-year-olds] need to complete their education at the very least.”

This perspective is reiterated by Hyshyama Hamin, co-author of Unequal Citizens, a study that documented Muslim women’s struggle for equality and justice in Sri Lanka.

According to Hamin, pushing for consensus isn’t a solution, especially as diversity of opinions will always exist. What can be done at this juncture, however, is to go for the most progressive reform possible. She stressed that there was no need for Sri Lanka to step back and work on reforms on a piecemeal basis, and pointed out that there is enough and more evidence, even Quranically, to go for the most progressive choice if there are dissenting opinions.

According to her, what needs to be done now can be summed up into two pertinent points. The first is to establish the process: how to provide feedback, what the timeline is, when it should be submitted by, and so on. The second is to study the report in detail.

“We need to really study the report to see if it addresses the issues women face. One of the things we know [through the previously leaked reports] is that the committee doesn’t acknowledge that women need to consent to polygamy. Then there’s no consensus on the minimum age of marriage as well,” she said.

Each of the recommendations, Hamin stressed, needed to be discussed and debated to ensure they met fundamental rights principles.

“The state has a responsibility to protect its people, and current lived realities need to be taken into account,” said Hamin, adding that Sri Lanka is bound by international statutes, and needs to meet basic requirements for human rights—which includes practising principles of equality among all citizens.

Government Response

The government’s silence on the report has been deafening up until now. Our attempts to contact Justice Minister Thalatha Athukorala were unsuccessful, while sources at the ministry themselves were unaware that the report had been released.

We will have a detailed summary and breakdown of the report in the near future. Meanwhile, you can learn more about the issue through our coverage over the last few years—including this video, and this piece detailing experiences of domestic violence and forced marriages linked to the MMDA.

.jpg?w=600)