If you drive north from Nilaveli along the B424 towards Pulmoddai, you come to a turn-off to the left: the B366, the Perkar Road. Drive about 2 km along this road and you encounter the Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation Radio High Power Transmitting Station. In 2011, the SLBC took over the Perkar station from the German broadcaster, Deutsche Welle, which operated a large relay station here from 1984 onwards.

Received wisdom has it that this site served as a radio station used by the Royal Navy when it occupied Trincomalee. In actual fact, the Perkar installation had been a top secret British signals intelligence (sigint) radio interception and decryption centre, similar to the famous one at Bletchley Park in Buckinghamshire. Like Bletchley, its origins go back to before the Second World War. Unfortunately, the British Government has revealed few details, so the story can only be pieced together sketchily.

Bletchley Park And FECB

In 1919, the British Government merged its separate Army and Navy signals intelligence services into a single agency, to which it gave the cover name “Government Code and Cypher School” (GC&CS), the ancestor of Britain’s modern Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ). Twenty years after its formation, GC&CS moved to perhaps the most famous address in code-breaking, Bletchley Park. The staff at Bletchley, deployed to several wooden outhouses (“huts”), broke the Nazi wartime “Enigma” and “Lorenz” codes. To deal with the latter, the GC&CS deployed the world’s first electronic computers, the “Colossus” series.

In the 1920s, GC&CS began decrypting Japanese codes. In 1935, it formed a signal-interception and code-breaking branch in Hong Kong, the “Far East Combined Bureau” (FECB), which worked in co-operation with the signals intelligence services of other British Dominions. On the outbreak of war in 1939, the unit moved to Singapore. This unit may have, with help from Soviet sigint, provided intelligence about the impending Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour.

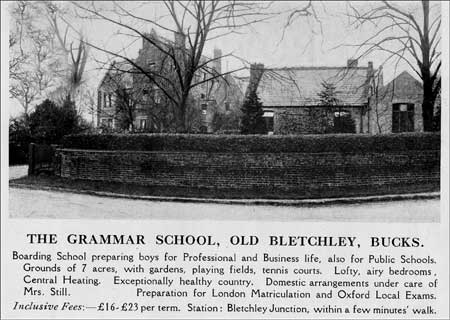

Meanwhile, in view of the lack of suitable linguists, Bletchley began training personnel from Oxford and Cambridge universities in Japanese. They were sent to the Japanese Naval Section, originally located at Elmers School in nearby Old Bletchley, but in 1942 moved inside Bletchley Park and relocated to Hut 7 the following year. Hut 7 provided cryptanalysts and linguists to FECB and served as headquarters for sigint operations against Japan.

Elmers Grammar School, the first location of the Japanese Naval Section. Image courtesy mkheritage.co.uk

Pembroke Academy To Kenya

When the Japanese attacked Malaya at the end of 1941, the British thought it prudent to withdraw, with the air and military intelligence units of FECS going to New Delhi, and naval ones to Colombo. The FECB staff evacuated from Singapore arrived in Colombo in January 1942, and were accommodated in hotels (officers) and hostels (other ranks and women).

Operating as “Captain on Staff, H.M.S. Lanka”, they established their radio interception and decryption centre at Pembroke Academy (a private “cram shop” in Flower Road, which closed in 1978). Radio aerials attached to the tops of trees and a Hollerith machine (an electro-mechanical predecessor of the electronic computer, using punched cards) evacuated from Singapore aided them in their efforts.

The code-breakers deciphered a Japanese message which indicated that the Imperial Navy would attack Colombo in early April. This enabled the British to withdraw the bulk of their fleet from Trincomalee to Addu Atoll in Maldives. Nevertheless, scepticism about the code-breakers’ abilities caused the loss of several ships, including the aircraft carrier Hermes (The wreck of which is now a favoured diving site off Batticaloa) and the cruisers Cornwall and Dorsetshire.

As a result of the Japanese raid on Sri Lanka, the British evacuated FECB to Kenya, where they set up in Kilindini. However, a few code-breakers left behind at the Pembroke facility played a vital role in the defeat of the Japanese at the Battle of Midway in June.

H.M.S. Anderson, about 1945. Image courtesy Pearl Hood and Stanley Wood School of Dancing

HMS Anderson

In August 1943, FECB relocated back from Kilindini to Colombo. Its head, Commander William Bruce Keith, a veteran of Bletchley Park, wanted to go upcountry, but Navy insistence that the unit be within easy reach of the Colombo Naval HQ foiled this intention. Instead, it settled on the Anderson Golf Links in Narahenpita, Colombo’s third golf course (the others being the Royal Colombo Golf Club’s Ridgeway Links in Borella and the Ladies’ Golf Links in Cinnamon Gardens).

Here the first purpose-built sigint facility in the East came up, also serving as a direction-finding (DF) facility for the Royal Navy. Named “H. M. S. Anderson”, this grew into the main British radio listening and cryptanalysis centre outside Britain. The British also maintained a joint Allied sigint centre at Peradeniya, attached to South East Asia Command (SEAC), and DF stations on Powder Island, Trincomalee, and at Hambantota.

A separate long hut, parallel to the main building, housed the Hollerith Machine. The Anderson site also accommodated the main radio receivers, and employed 100 receiving bays in the main receiving room, monitoring communications between the key Japanese bases in South East Asia, with each operator being given a single Japanese channel to cover.

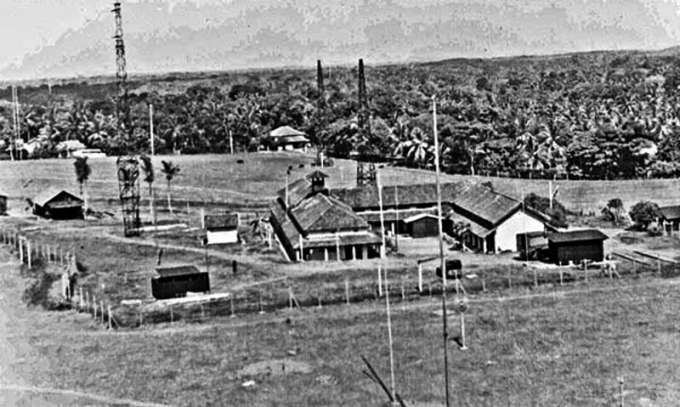

However, outward communication took place via external transmitting stations, such as the Royal Air Force (R. A. F.) signals centre at Gangodawila (the current site of the University of Sri Jayawardenapura). Communications between Narahenpita and the transmitters took place via landlines. However, the locals took to stealing the valuable copper wire, causing frequent shutdowns—a problem solved eventually by introducing a microwave link.

R. A. F. Gangodawila. Image credits: Anthony Cunnane

Staff

The base employed a large staff—1,280 by 1944, with a planned expansion to 1,700; few of them civilians. Apart from the naval staff, H. M. S. Anderson also held 190 R. A. F. personnel to provide small “Y” parties (consisting of “computers” and telegraphists) to be deployed in ships to give warning of air attacks. Several hundred “wrens” of the Women’s Royal Naval Service operated the Hollerith Machine, or served as intercept operators, traffic analysts, cipher strippers, signal type identifiers or clerical staff.

Recreation inside H. M. S. Anderson, about 1945. Image courtesy Pearl Hood and Stanley Wood School of Dancing

These personnel found accommodation mostly outside the base. The wrens were billeted in St Peter’s College and at Kent House in Flower Road, mainly in badly lit and ventilated cadjan huts (known as “bandas”). Despite their grim housing, the staff enjoyed themselves, relishing a range of food unavailable back home, swimming at Mt. Lavinia or Galle Face, and enjoying the exotic nightlife. Colombo had one night club, the Silver Fawn (nicknamed “the Silver Prawn”), but many other ranks preferred a house nearby where ladies served tea, cakes, cool drinks, and banana fritters. Entertainment was also provided by an in-house concert party, “The Anderson Players”. Keith encouraged a more relaxed atmosphere than usual on a naval base, stemming from his time at Bletchley Park.

“The Anderson Players”, H. M. S. Anderson, about 1945. Image courtesy Pearl Hood and Stanley Wood School of Dancing

Commander J. E. Poulden, who served as Keith’s deputy, later went on to serve as first Director of the Australian Defence Signals Bureau. John Silkin, later a Labour Party cabinet minister, served at H. M. S. Anderson as a linguist. Others who worked here included two naval telegraphists, D. O’Reilly and F. S. Murphy, who wrote to the left-wing Tribune, opposing British intervention against the fledgling republic in Indonesia.

8°44’35.5″N 81°07’50.2″E

Satellite image of Perkar, courtesy Google

As a precaution against the anti-British agitation which occurred around the time Sri Lanka gained dominion status in 1948, the British deployed marines and sailors from a cruiser in Colombo harbour to defend H. M. S. Anderson and its staff billets. They kept the Government of Sri Lanka in the dark about the true nature of H. M. S. Anderson, making out that it was simply a communications relay station.

In 1950, the Government informed the British that it wanted to re-develop the Anderson Golf Links (the Anderson Flats were built here later) and asked them to remove H. M. S. Anderson from the site. British officials agreed, since they believed (correctly) that the real purpose of the installation could be hidden at a new site. However, finding one proved difficult, as they planned on an upgraded facility, capable of receiving signals from all bearings, which necessitated 400 acres of land to accommodate the radio aerial “farm”. Furthermore, the site could not be too remote, but at the same time needed to be isolated from interference from highways, towns and naval movements.

Accordingly, by 1952 officials of the Admiralty and GCHQ agreed to build the brand-new purpose-built sigint facility, with the capability of expanding rapidly in wartime, at Perkar, located at 8°44’35.5″N 81°07’50.2″E. In 1954, after building the base at a cost of £2 million (Rs 10 billion today) to construct, they shifted operations from H. M. S. Anderson to Perkar. Again, they used the “relay-station” cover story on the Government.

Leave, However Dressed

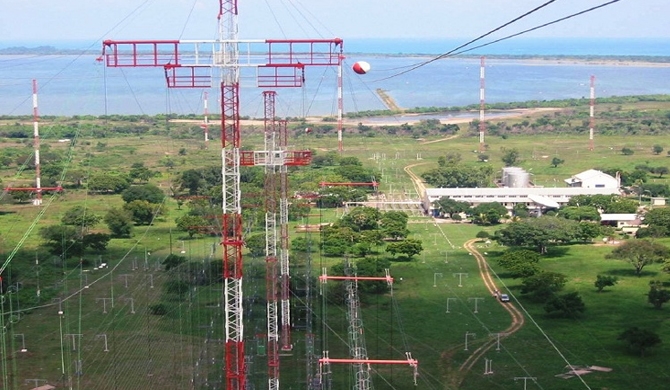

The Deutsche Welle relay station at Perkar. Image courtesy Sri Lanka Mirror

However, external events put paid to the new base. In 1956, Britain and France, in collusion with Israel, attacked and captured the Suez Canal zone, recently nationalised by Egypt, causing an international uproar. The Government of Sri Lanka, convinced that ships used in the operation had been refuelled at Sri Lankan ports, asked the British to provide a timetable for removing their bases.

The British, caught flat-footed, stalled for time. They suggested that the base facilities remain, disguised as civilian installations, with service personnel to be dressed in mufti. However, Prime Minister S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike would have nothing of it, insisting that the British would have to leave, however dressed.

Ultimately, the two sides reached a compromise—the base facilities would be removed gradually over five years. The Royal Navy gave up its base at Trinco in 1958, but retained two naval signals stations at Welisara and Kotugoda (lumped together as “Ceylon West Radio Stations”), and Perkar. In 1962, the Royal Navy handed these sites over to the Royal Ceylon Navy, which had almost no sigint capability, and which abandoned Perkar.

This writer visited Perkar in the early 1970s, and found a large building, with thick concrete walls, occupying its centre. It had obviously missed human occupation for many years, since it reeked of bat guano, which lay thick on its floors. Its occupation by Deutsche Welle, later, proved a godsend, as the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam may have otherwise converted it into a bunker. Today, it is devoted to civilian tasks—transmitting in Sinhala to the Middle East, a far cry from its covert origins.

Cover image courtesy: Pearl Hood and Stanley Wood School of Dancing