“When they imposed the curfew on Minuwangoda [on Sunday, October 4] we thought this could happen to us too—but over the weekend—because we’re around 15km away,” Thilanie (32), a resident of Ja-Ela told Roar Media.

“But not so suddenly. When they imposed it, I had to rush.”

Hurrying back from work to gather supplies before returning home, Thilanie noted that there were already shortages in most major supermarkets. “We managed with what they had,” she said. “I got the fresh stuff — vegetables, meat — from a supermarket. The rice and other things I needed in bulk, I got from a wholesale supplier.”

The Minuwangoda Cluster

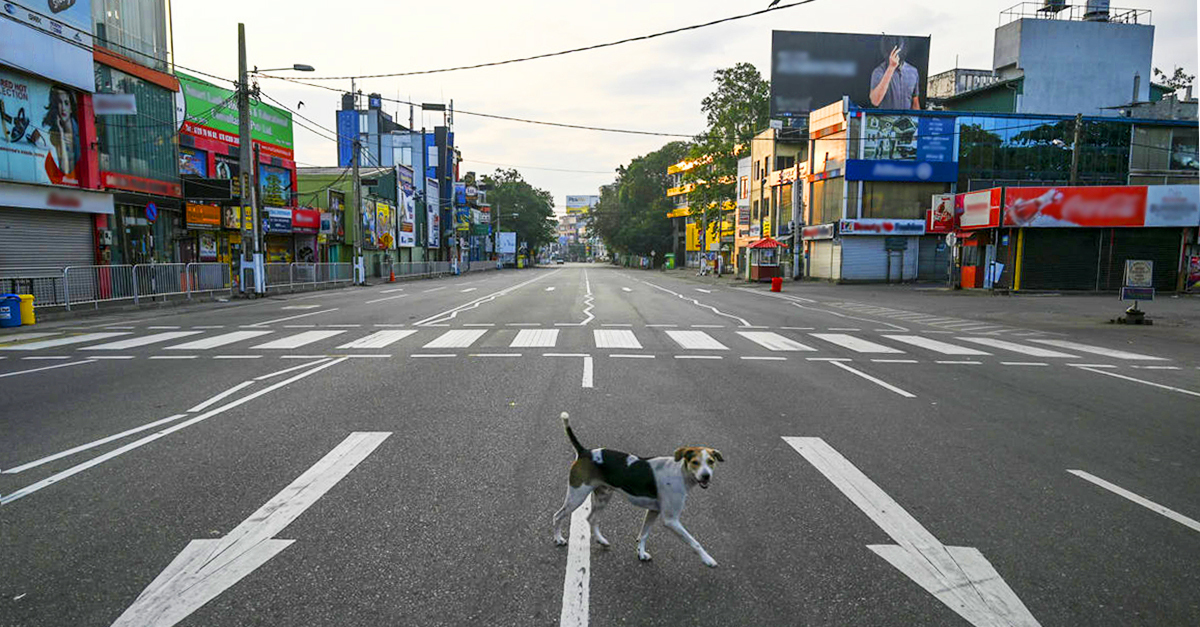

Curfew was announced in eighteen police areas—including Ja-Ela—on Wednesday, October 7, following the discovery of a COVID-19 patient at a prominent apparel factory in nearby Minuwangoda. This ‘Minuwangoda cluster’ has grown to become Sri Lanka’s largest COVID-19 cluster to date.

This is the first cluster to emerge from outside quarantine centres in two months, the last being the ‘Navy cluster’ that first began in April. It is also the first since the government announced an end to community transmission of the virus in May, some three weeks after a three month lockdown was lifted.

But this time round, there seems to be no coordinated attempt to distribute food supplies to areas under curfew, those in the affected areas said. “Only the choon paan [bread] seller comes around,” Thilanie said. “There’s no real plan.”

Supply Shortages

That Friday [October 9], the Sri Lanka Police permitted supermarkets, pharmacies and other food outlets in areas under curfew to open from 8 AM to 8 PM. But Thilanie said there were barely any delivery options— only one major supermarket chain had offered delivery.

She also noticed there was a hefty increase in the prices of essential items like rice and onions, both in supermarkets and at wholesale outlets. “At the moment,” she told Roar Media, “I believe we have enough to last another five or six days. But after that, I don’t know what to do.”

Zulsha (28), also in Ja Ela, lives within a housing scheme. “Currently, the shops are open over here, and they don’t have any restrictions, because we didn’t have any people who tested positive from inside [the housing scheme],” he said. “But no one can go out, nor can they come in.”

And not being allowed to go outside the scheme may prove difficult in the long term, he feels. “Soon we’re going to face a shortage because there’s no access to going out or coming in,” he said. “Basic things like eggs, meat, vegetables, these are going to run out soon.”

No Delivery Options

Shehan (30), who is from the Gampaha police area, said he received the alert about the impending curfew that morning. “I had until 6 PM to prepare,” he said. Assuming that he wouldn’t need to rush since he was working from home, he took a little while to leave the house, but said he found the stores already crowded.

“I didn’t want to go to any places like that because it’s risky,” he said. “And because it was not good news that was going around. But because it was crowded everywhere, I didn’t get anything. I just came back home.”

Shehan’s main concern is for his six-month-old son. “I tried to contact some pharmacies to get diapers,” he said. “But the pharmacies were closed. We had to manage with the 10 or 15 we had left until we were given permission to go out. That was a major issue for us.”

By Friday, just two days after curfew was imposed, Shehan said there were already shortages in multiple supermarkets in his area, even though queues had formed outside many of them. Flour and lentils, he said, were particularly scarce, and delivery was not an option—many food delivery services do not operate within Gampaha in general, and supermarkets in curfewed areas had not yet managed to gain necessary authorisation to carry out home deliveries.

“I was under the impression that this time wouldn’t be like the initial stages of the previous lockdown, but the latter stages, where we had some good delivery services in place, and there were also some small shops in the areas delivering,” he said.

“But unfortunately, it’s not like that.”

Empty Shelves

In Yakkala, Hasanthi (42), believes that although the islandwide lockdown earlier this year may have prepared people—mentally at least—for the current situation, supermarkets and smaller shops are already facing supply shortages.

“Lots of shelves were just empty,” she told Roar Media, noting a scarcity of eggs and vegetables in particular.

Besides access to basic necessities, the indefinite nature of the current curfew has made many particularly anxious. “Looking at the spread and the way it’s continuing, we really don’t know how long it’s going to be for us,” Hasanthi said.

“Last time, we had lorries and people with permits who would come in with dry rations or vegetables. This time, it’s going to be a bit different. I think people have to be really careful with what they buy and how they use it. It’s really difficult to predict, this time.”