“සුද්ධිට අගෞරව කරන්න හොඳ නෑ (we mustn’t disrespect Suddhi)” is an oft-repeated motif in Prasanna Jayakody’s third outing, 28. The irony that this respect is demanded for the dead body of a sex-worker, is at the heart of this deceptively light-hearted road-trip adventure. The filmmaker succeeds, for the most part, in highlighting it in a way that thankfully doesn’t feel hamfisted, inviting the audience to reflect and ponder on their own inherent hypocrisies. Littered though it is with moments of [occasionally forced] hilarity, the film’s central theme is a powerfully evocative dissection of the woman’s role in the increasingly sexually frustrated society the film is set in.

According to 28’s marketing campaign, the film sets out to explore the tragedy of how rape and sexual abuse have become so rampant in a society that ironically sees sex as a sociocultural obscenity. By and large, director Jayakody manages to cleverly drive home the point that (at least according to this writer’s interpretation of the film), ultimately, sex remains a taboo in Sri Lankan society by design—as a form of control. Sex is and will likely remain a monopoly of men, and the handful of women that dare challenge that status quo will be put in their place by any means necessary—be it rape, slut-shaming, victim-blaming, or even murder.

Mild spoilers ahead…

Starring Mahendra Perera, Semini Iddamalgoda, Sarath Kothalawala, and Rukmal Nirosh, 28 tells the story of three men transporting the body of a dead woman from Colombo to a remote village in the hill country in an ancient Delica van (numbered 28-Sri), so that the family she had once married into could pay her their last respects. As the story unfolds, we learn that the woman (Iddamalgoda), affectionately referred to as Suddhi, was a sex-worker who had purportedly been raped and murdered under mysterious circumstances. She also happened to be the estranged wife of one of the men, Abasiri (Perera), a tough but unassuming gem mine worker, who is sensitive sans the usual naivete audiences have come to expect from such characters in contemporary Sinhala cinema.

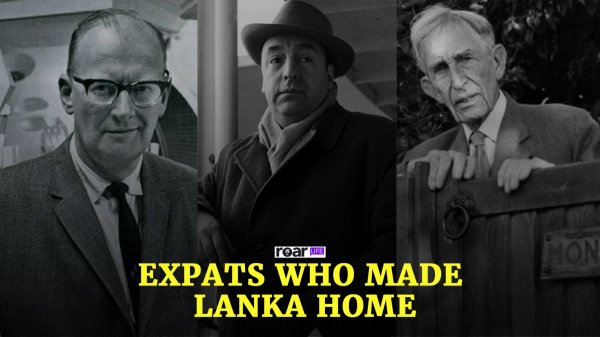

Semini Iddamalgoda, who plays Suddhi. Image courtesy alphaviolet.com

28 is not a perfect film, though it comes pretty close. The only really glaring flaw, for this writer, was that, although the chemistry between the three men is strong, some of the jokes—particularly those at the expense of Sarath Kothalawala’s otherwise well-written character—don’t really land, and for the briefest of moments breaks the immersion somewhat. Fortunately, however, none of the humour—forced or otherwise—takes away from the central theme of the film. Of course, the real tragedy here is that this internationally acclaimed gem of a film took four years to get a wide release in its own country since its initial festival run, but that’s a rant for another time. Though its overall message does veer dangerously close to on-the-nose territory at some points—as Sinhala art house films tend to do—28 is, for the most part, an exercise in artful subtlety, occasionally punctured by a gag that some moviegoers may find drags a second too long. Given the emotional weight of the core story, however, the at-times forced humour is not entirely unforgivable. Indeed, a lot of the film’s comedy feels refreshingly natural and is genuinely funny—the kind of humour you’d be hard pressed to find in any locally produced, post-Joe Abeywickrama comedy.

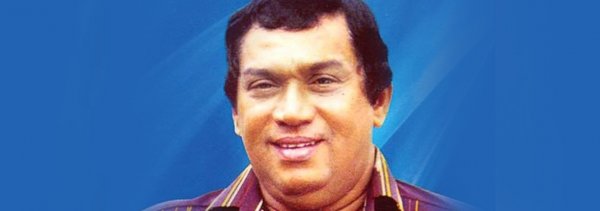

Mahendra Perera, Rukmal Nirosh and Sarath Kothalawala as Abasiri, Mani and Lenin respectively. Image courtesy iffr.com

From start to finish, 28 is an ode to women and the price they pay for the blatant hypocrisy of the men whose needs whims and fancies they fulfill, even if much of the screen time is taken up by three men. That director Jayakody is able to do this without resorting to insufferably heavy-handed lecturing—even as Suddhi’s dead body routinely breaks the fourth wall and literally talks to the audience through a crack in her coffin—is an achievement in its own right. Particularly given the above-mentioned tendency of local filmmakers to forcefully hammer their message home at the expense of believability. (The usually brilliant Ashoka Handagama’s Let Her Cry being a recent example).

The gender politics at play here is simultaneously understated and powerful, and Jayakody, through Iddamalgoda’s haunting performance (no pun intended), manages to portray the harsh realities of everyday sexual objectification in Sri Lankan society. The director also shatters the myth that the village is a place of moral tranquility devoid of vulgar excess. Abasiri’s own father, we learn, was among the villagers who reduced Suddhi to an object to be lusted after. Both Jayakody and Iddamalgoda deserve praise for pulling this off, confined as the latter was to a coffin, through some of the best-written dialogue and narration in recent memory.

Mahendra Perera gives a performance of a lifetime as Abasiri in the internationally acclaimed 28. Image courtesy ceylontheatres.lk

Particular praise should go to Mahendra Perera (arguably the most talented actor working in film today) who gives the performance of a lifetime as Abasiri. He skillfully and often non-verbally portrays the conflicting emotions of a man who just saw his wife of 15 years naked for the first time as her motionless body lay in the morgue. Unable to endure any more of the taunts and lustful gazes of the men in their village, Suddhi was forced to leave, abandoning Abasiri to a life of misery and loneliness. Years passed and Abasiri had given up his search for her when he was summoned to identify her body. And yet, he bears no resentment and insists on being respectful towards the woman he once loved. If he is feeling any grief or guilt at all for what happened to her, he doesn’t really show it—not immediately, anyway. Abasiri’s inner turmoil is thankfully not spelt out to the audience, and Perera does a good job of capturing the gamut of his character’s emotions in a dream role that’s comical, endearing, and utterly heartbreaking, all at the same time.

The two supporting actors, Rukmal Nirosh and Sarath Kothalawala, are also commendable, providing much of the humour in an otherwise serious film laden with heavy themes. Kothalawala, in particular, shines as Lenin, the disgruntled driver of the rickety old ice cream van, who is tricked into transporting a dead body. (Aside: keep an eye out for a nifty long-take of the three men carrying the heavy coffin for a full minute and a half to higher ground in order to put it back on the van’s roof.) The film features some top notch cinematography by Chandana Jayasinghe, ably complemented by Dheshaka Bamunumulla’s captivating score.

Director Prasanna Jayakody. Image courtesy alchetron.com

Without giving too much away, the film’s very last scene is where Jayakody really delivers. In the hands of a lesser filmmaker or cast, this single moment could’ve ruined the otherwise poignant and evocatively immersive experience that was 28. It’s a testament to Jayakody’s skill as a director that he pulls it off as well as he does—and, of course, Perera’s immensely enviable acting talent.

Overall, 28 is a rare treat, an almost-masterpiece, that speaks to the audience while telling a small but by no means unimportant story, without getting bogged down by its own politics. It’s not without its faults, of course, but nothing that the average Sri Lankan filmgoer can’t look past.

8/10.

Featured image courtesy alphaviolet.com