Is there a correct way to speak English? Here, on our little island, it is a widespread belief we should aspire to a version of English that is essentially British, and that anything less than the Queen’s English is a travesty and embarrassment.

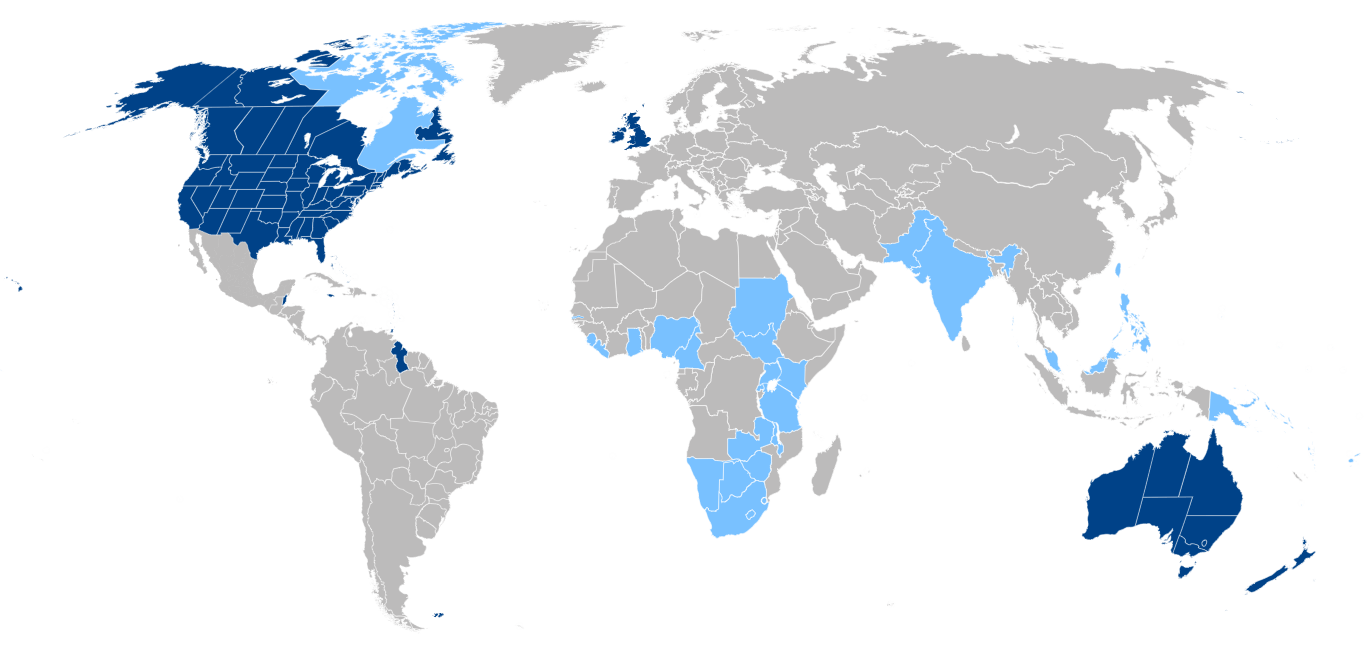

But, this antiquated notion ignores the fact that English in Sri Lanka, as with many other former British colonies, has developed into its own unique variant, known now as Sri Lankan English (SLE).

The recognition of SLE was previously only in academic circles, as it was considered ‘incorrect’ by speakers of ‘proper’ English. However many now see that ‘our way’ of speaking English is something to recognise and own.

In 2007, Michael Meyler, a Britisher who has lived in Sri Lanka since 1985, published the first comprehensive compilation of the features of SLE. His ‘A Dictionary of Sri Lankan English’ documents words, phrases and expressions commonly used by English speakers in Sri Lanka.

What Is Sri Lankan English?

Almost everybody who speaks English in Sri Lanka uses features of SLE, but often don’t realise that these features are unique to Sri Lanka. “It was easier for me, as an outsider, to spot those features,” Meyler told Roar Media.

Meyler’s dictionary is designed for three sets of people: teachers and learners of English in Sri Lanka, foreigners in Sri Lanka, and academics interested in the varieties of English.

But a fourth group he hadn’t anticipated, were ordinary English-speaking Sri Lankans. “They recognised that this was the English they spoke, but had never realised, or been told, that SLE was a thing, and that they could be proud of it,” he said.

Meyler related how many people had found his dictionary amusing—which it wasn’t meant to be, “but I think that shows that it struck a chord with people here, that they found it relatable,” he said.

Meyler, who began collecting examples of SLE almost as immediately as he moved to Sri Lanka, said that he was aware of the difference from the time he arrived. “I started making lists of these,” he said. “The first printed list I made was typed on an old- fashioned typewriter, and the first thing I ever did on a modern style computer, was to type up my list of words!”

Sri Lankan English is unique and is often poked fun at. Video credits: Youtube/JehanR

Meyler’s dictionary not only lists words and phrases, but also grammatical features not used anywhere else, such as with the word ‘had’, in the use of the past perfect tense. In Sri Lanka, one can say “The robbers ‘had’ escaped in a white van,” when it is possible to simply say “the robbers escaped in a white van”.

A feature common in news articles, Meyler explained that “when a Sri Lankan is using the word ‘had’ in this context, he is not stating a fact, but something he’s heard as second-hand information. In standard British English, one can similarly say “he told me, that the robbers had escaped in a white van. [But] in Sri Lanka, just adding ‘had’ is enough to signal this.”

There are also two distinct, but linked, varieties in the usage of SLE. These are differences between A. first language speakers B. bilingual speakers. Meyler also explained that these difference are analogous to the two different generations—the older colonial, and the modern bilingual.

The younger generation, he said, often uses a more globalised or international form. Additionally, where Sinhala or Tamil is the first language, more features of SLE come from these languages.

For the older generation, however, archaic British terms or expressions, like, ‘dickie’ to refer to the boot of a car, are still in use. Meyler pointed out that it is also very rare among younger English speakers (who would use the word ‘boot’, or ‘trunk’ to describe the storage compartment at the back of a car) to use slightly formal words and phrases like ‘Do the needful’ ‘hence’ and ‘hitherto.’

“Even within a small country like Sri Lanka, and even within the relatively tiny English-speaking community, there are several sub-varieties of Sri Lankan English,” he said. “Sinhalese, Tamils, Muslims and Burghers speak different varieties; Christians, Buddhists, Hindus and Muslims have their own vocabularies; the older generation speaks a different language than the younger generation; and the wealthy Colombo elite (who tend to speak English as their first language) speak a different variety from the wider community (who are more likely to learn it as a second language).”

English And Class

How a person speaks English in Sri Lanka brings with it a baggage of information about their life. “With language, you don’t really want to stigmatise people based on their social class, but inevitably, the way some people speak English carries more social weight,” Meyler said.

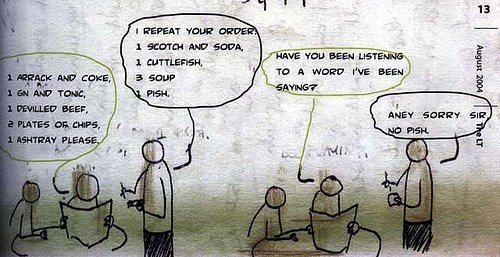

Amongst English speakers here, the subtle ways in which someone speaks the language, uses words, expressions, and pronunciations, can reveal their social class, profession or hometown. For instance, the /f/ sound, present in English but absent in Sinhala, is often replaced by /p/ when pronounced by native Sinhala speakers.

Thus, ‘office’ is sometimes pronounced ‘oppice’ or Finland would be referred to as ‘Pinlanthaya’.

Features like these, more prominent in the newer, Sinhala influenced SLE, are derided by speakers of the older, British influenced SLE.

Recognition As A Variety of English

Indian English, in contrast to SLE, has been recognised as a distinct variety from very early on. The first Indian English dictionary—Hobson-Jobson: A Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words and Phrases, and of Kindred Terms, Etymological, Historical, Geographical and Discursives—was published in the colonial era, compiled by British writers trying to help English people with local words.

“Since then, the post-independence Indian government has taken ownership of Indian English in a way the Sri Lankan government never did,” Meyler said.

Meyler’s work is widely recognised, and has enjoyed the acceptance of academics studying SLE, but as with most work, it has also attracted criticism.

Academic Arjuna Parakrama, currently Professor of English at the University of Peradeniya, believes that SLE is no more (or less) difficult to describe than any other variety of English elsewhere in the world.

In a paper entitled, ‘Extra-Linguistic Value (of English in Sri Lanka)’, published in 2016, he writes, ‘There is a lot of whining and whingeing here about the complexity and difficulty surrounding all aspects of SLE. It is precisely this kind of defensive and apologetic discourse that characterises writing and thinking in our field. All of the situations described are common to all language contexts the world over.’

Meyler has sympathised with his position; “You have to draw a line somewhere, even if it is an artificial one, or a superficial one,” he said. “When writing the book, I had to choose what were mistakes and what were features. For instance, phrases like “when you come?” or “where you go?” I would not consider being standard SLE. And although I would personally say that is incorrect [English], one could argue that that too is a part of standard SLE.”

For Meyler, what it comes down to is the clarity of communication. “The fact that you’re speaking Sri Lankan English, or Indian English, doesn’t mean that you’re unable to communicate with other English speakers in the rest of the world,” he said. “Of course someone may use a word that the other doesn’t understand, but that’s the same as when I go to Scotland!”

Teachers should make themselves aware of the way the language is spoken here, and then be tolerant, Meyler said. “While it is important to correct mistakes where there are mistakes, it is as important to realise that some things shouldn’t really be categorised as mistakes,” he said, explaining that it should simply be chalked down to the “natural way” people use the language.

Meyler is now working on the second edition of his dictionary, which, in addition to new entries, will have more detailed citations. “It will show examples of how SLE is used in different media, such as newspapers, magazines, novels, as well as in online forums and comments,” he said.