Ever thought of Sri Lanka recognising her doppelgänger?

Perhaps if you haven’t, let’s consider bringing Kerala, a state sewn against the Malabar Coast of South India, into the picture. What’s more ‒ a link between the two places can be traced back as far as the ‘Pattini’ (a guardian deity of Sri Lanka) cult from the Chera country, as Kerala was once known. The similarities shared by both regions are, in fact, astonishing upon close scrutiny.

Coconut

Coconut palms in the village of Anjengo, Kerala. Image Credit: Emmanuel Dyan/National Geographic Traveller India

The answer to the question of where coconuts first originated is an unsettling one. However, Kerala that prides itself with the populous of coconuts throughout the region seems to have earned its name from kera meaning coconut palm in the Malayalam language. In fact, as one of Kerala’s ever-fertile plantations, coconut covers 40% of the land and remains one of the state’s most revered procurement benefitted by both its economy and culture. This can be also identified in Sri Lanka. Our very own pol has been blessed, in the same vein, with a sharp strength in number in and around the coastal belts, with approximately 2,500 million nuts produced islandwide each year. Coconuts, as a result, are a big deal in Sri Lankan cuisine. Almost every dish in Kerala and Sri Lanka comes complete with coconut whether in the form of oil, desiccated or scraped coconut, or coconut milk, though of course, the food of each region is infused with their own unique flavour.

Toddy

A Sri Lankan toddy tapper. Image credit: Roar/Nazly Ahmed

The Illavar or Ezhava community of Kerala who once established toddy tapping as one of their chief occupations, among others such as coir making, are said to have moved into Malabar from Ceylon. According to legends, the practice of toddy tapping can be traced back to the Chera Kingdom of Travancore in the 1st century CE. It seems the Ezhavas were the descendants of a few bachelors that the King of Ceylon at the time had shipped off to Kerala at Chera King Bhaskara Ravi Varma’s behest, for the setting up of coconut farming in Kerala. Based on this, it is perhaps easy to believe that Sri Lanka may have had an influence on toddy tapping in Kerala, although there has been no actual record of this. Today, the precarious climb for toddy is arguably a unique area of expertise on its own. The cotton-white liquid extracted as sap from the tree is wholly non-alcoholic before thrown into fermentation and the dipsomania attained thereafter. Toddy, which is believed to be a sacred offering to the Gods, is famously known as kallu or kali in regions of Kerala and served along with kappa-meen curry (a local fish curry) at every toddy shop around; here in Sri Lanka, the toddy sphere includes thal ra, kithul ra, or the pol ra best stored in earthen pots.

Spice Trade

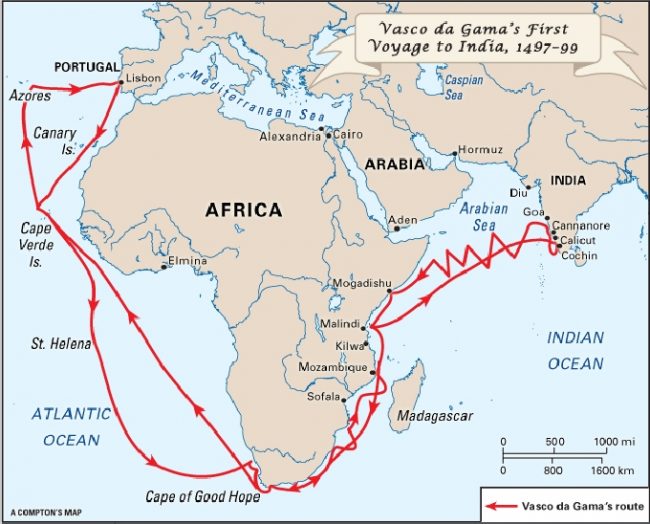

The Route taken by Vasco De Gama to India. Image courtesy: justalittlefurther.com

The arrival of Vasco De Gama and his crew at the shores of Calicut (now Kozhikode) was a revolutionary one — when men, as if to portray their voyage purposeful, shouted, “For Christ and spices!” So, as far as cannonballs could aim, Calicut along the Malabar coastal stretch was and still is known to be the supreme hub in the world’s black pepper-growing industry, attesting a highly profitable rate in the market, what with the foreign demands for pepper. Sri Lanka was not too far off, being much the same in the lead even after the Europeans invaded. In addition to this, Arab Persian Zakariya al-Qazwini in 1270 recorded that cinnamon was native to Sri Lanka ‒ which today produces 90% of world’s cinnamon. Eventually, the spice trade opened doors to migration from and to the island, and Kerala experienced a similar fate. Both places thus held mutual significance in the taste and trade of spices despite undergoing problematic colonial invasions.

Ayurveda

Ayurveda, containing healing properties, is known for its perfect mix of balance and bliss. Image courtesy: hotelfresh.lk

Gifted with the constant contact with spices, Sri Lanka and Kerala are very specific about indulging in the holistic approach of Ayurveda, which is considered as one of the oldest healthcare systems. Sources suggest that Kerala was under the influence of Buddhism; this, along with the congenial atmosphere and the rich soil helped to deeply nurture the science of Ayurveda, aided by the Sanskrit texts. Further, evidence claims that many Ezhavas were competent ayurvedic physicians, and among them the best known was Itti Achuthan, an Ezhava himself. [1]

Climate And Landscape

Tea plantations in Munnar, the hill station of Kerala. Image courtesy: keralatourism.org

In both Sri Lanka and Kerala, the abundance of tea-plantations, rainforests, rivers, waterfalls, wildlife sanctuaries, and the pristine beaches have proven to contribute towards the growth in the tourism.

Further, rainfall in Sri Lanka varies between 2,540 mm to over 5,080 mm in the south-west ( Kandy basin) of the island. Much of these occurrences are strikingly apparent in Kerala during monsoon season as well. Designated by the UN as a World Heritage Site, the Western Ghats including Wayanad and Munnar in particular, proudly sit among fertile tea-estates. This naturally tempts the South-west monsoon showers to boast a 3,000 mm of rainfall in Kerala each year, between June and September. Not only are nature enthusiasts constantly drawn to Munnar or the backwaters that are alive with houseboats in Kerala, but adventure seekers in Sri Lanka, too, eagerly wait to trek up the hills, at either the Knuckles Range or the panoramic Ella.

Food

Fishermen in Kerala. Image courtesy: thehindu.com

Fish, to both Sri Lankan and Kerala cuisine, is unavoidable as well as vital. It’s no surprise that one of the most celebrated foods in Sri Lanka comprises of what is freshly caught and what smells strong. The island offers a variety of over 200 fish to eat, including yellowfin tuna (kelawalla), sail fish (thalapath), and spanish mackerel (thora malu). One of Sri Lanka’s favourite fish dishes is undoubtedly the ambul thiyal, prepared with halibut or tuna in a bath of gravy, a Southern hot and peppery specialty. Similarly, the Malayalee fish curries are endless ‒ from fish mappa to meen alleppey, and the karimeen (pearl spot fish) fry, which remains a prominent dish served on a banana leaf.

In addition to this, fruits such as bananas and pineapples grow in abundance thanks to the tropical effect. The breakfast of both Lankans and Malayalees very much belong to the aesthetics of kindred spirits as well. The appam, idiyappam and puttu have slightly been altered in name and serving only (with a dollop of katta sambol accompanying the Sri Lankan meal).

Elephants

Elephants at the Kandy Esala Perahera. Image courtesy: wikimedia.org

As Indian author, Shashi Tharoor, accurately puts it, “Elephants infuse the Kerala consciousness.” [2] Deeply embedded are the islanders’ sentiments for elephants, too. This can be witnessed at the Kandy Esala Perahera festival in the months of July and August every year. The ceremony comes complete with brightly primped up elephants in ornaments swaying as if hit by a breeze— one of them in charge of the Sacred Casket stored under a well-crafted shelter on its back, until the destination, the Dalada Maligawa, is reached. Likewise, in Kerala, there occurs the Thrissur Pooram; a Hindu temple festival graced by a neat stream of elephants draped with elaborate headdresses and crafted umbrellas. Scholars also have pointed out the exporting of ivory to the West from both Ceylon and the Malabar coast during the early centuries. Elephants have indeed made a vivid impact on both cultures, and were considered valuable for mercenaries in the island as much as for the Malayalees in the Indian mainland.

Thrissur Pooram festival, Kerala. Image courtesy: blog.goibibo.com

People And Social Systems

Anthropologist Michael Roberts has asserted that popular dynasties such as “the Macan Markars and the Abdul Cafoors migrated to Ceylon in the 18th or 19th centuries from Kerala”. This, in a sense, establishes the migrants of Malayalee progeny to the island. Moreover, sources say that Markar is a name commonly found in Cochin.

Furthermore, with regards to physical features, both Sri Lankans and Malayalees possess many similarities, beginning with a complexion that ranges from wheatish to dark brown.

Anthropologist Dennis McGilvray points out that the Moorish identity in the coasts of Malabar and Sri Lanka is said to have been the result of the medieval Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms allowing Arab merchants to settle for fiscal (in ports such as Calicut and Colombo) and perhaps later, inter-marriage purposes. [3] This not only unifies the waking of ethnic development with Islamic impact on the two regions before the British and the Dutch colonial rulings began, but also supports the theory of the spice trade as mentioned earlier.

The Caste system plays a very strong role in the South Asian context. Exploring further, the Rodiyas seem to be the widely sourced ‘untouchables’ amongst the caste system of the Sinhala people. Among the Shudras of Kerala on the other hand, the Paraiyars were of the lowest traditional Indian social class. Both, during the 18th and 19 centuries, experienced the worst conditions in the hands of colonisers and kings with their rights taken away (such as the prerogative to cover their upper bodies) and were often oppressed: either deemed culpable, or required to do the dirty work.

Other historical similarities include the devotional cults of Naga (snake) worshipping among Sri Lankan Tamils, which have clear connections in religious beliefs with the Nair community of Kerala, as it is still practised today.

While social interactions between Kerala and Sri Lanka were established through port settlements in the early centuries, the migrant workers of Kerala settled in the Middle East for better employment opportunities, in a manner similar to that of the Lankan migration to the Gulf. Even with finer influx of revenue attained, it seems that the lifestyles of workers from both places remains deplorable and unregulated. Many Sri Lankans and Malayalees live without proper sanitation and living conditions, thus making even our adversities all the more mutual.

Arts And Architecture

A Sri Lankan devil mask dancer. Image courtesy: gatewaylankatours.com

The town of Ambalangoda is known for its mask-making industry. Such traditions, including devil dancing, are said to have absorbed some influence mainly from the cities of Kerala and Malabar with more techniques added in the manufacture of masks as it has evolved today. Meanwhile, an important element to also note is the Angampora, the traditional martial art of the Sinhalese which possesses similarities to Kalari Payattu, a Dravidian combat system practised in parts of Kerala.

Kerala is famous for kathakali – another dance form involving a mask and a colourful costume. Image courtesy: ias.org.in

In architectural respects, a more shared feature is the structural patterns found in Kerala’s traditional homes enriched with the Portuguese, Dutch and British Victorian styles to that of the traditionally Lankan walauwa. Both complexes constitute a typical courtyard, Mediterranean arches, a verandah, strong pillars, and the Southeast Asian roof gestures. It is also believed that the conically roofed temples and palaces of Kerala, once under the influence of Buddhism and Jainism, may hold similarities to the ancient vatadage once found in Lanka.

With that, one is left contemplating hopefully, that future prospects of Sri Lanka and Kerala will involve a strengthening of alliances for mutual benefit, just like in the good old days.

Sources cited:

[1] Madhav Gadgil, Ecological Journeys

[2] Shashi Tharoor, Bookless in Baghdad and Other Writings About Readings

[3] Dennis D. McGilvray, Arabs, Moors and Muslims: Sri Lankan Muslim ethnicity in regional perspective

[4] Samanth Subramanian, Following Fish: Travels Around the Indian Coast