It has been three and a half centuries since the Portuguese colonisers left Sri Lanka, but the language they spoke while here still lingers in the eastern coast of the country.

Although few are aware of the existence of this language, Sri Lankan Portuguese Creole (SLPC) is spoken by the Portuguese Burghers, descendants of the early mestiços or the people of mixed Eurasian origin. This language was formed in the contacts between Portuguese and Sinhala and Tamil, and became an important lingua franca—a language used to bridge communicative gaps between speakers whose native languages are different. SLPC is spoken in many parts of Batticaloa and Trincomalee—including places with a large concentration of Burghers—such as Dutch Bar, Sinna Uppodai, and Palayuttu. The areas of Akkaraipattu, Kalmunai, Valaichchenai, and Eravur too are home to many SLPC speakers, though they are lesser in number than in the areas mentioned previously.

A short documentary produced by the Sri Lanka Portuguese Burgher Foundation and the Burgher Union of Batticaloa about Portuguese creole and its users.

Like many other creole languages, SLPC, or ‘Ceylon Portuguese’ as it was referred to in the early days, was often thought of as a corrupted version of Portuguese and described as ‘broken Portuguese’ or ‘lower Portuguese.’ Modern linguists have highlighted the importance of studying contact languages and the circumstances that led to their evolution; it is an indirect way to study the diverse ethnic and cultural groups who needed a common means of verbal communication that would be understood by both groups.

“In situations where two or more speech communities come into prolonged contact,” explained Senior Lecturer of linguistics at the Open University, Dr. Vivimarie Vanderpoorten Medawattegedara, “languages known as ‘pidgins’ usually develop. When this contact goes on for some time, a new language emerges—a hybrid language.”.

Dr. Medawattegedara further said that a pidgin is a language in its own right, with its own unique rule system. However, she noted that pidgins tend to have a restricted vocabulary and very simple syntax, because they were designed specifically to enable two culturally diverse groups of people to intercommunicate in matters like trade, local commerce, land disputes, or marriage negotiations. “Pidgin speakers also had their own native language and usually switched to pidgin only when necessary,” Dr. Medawattegedara added.

She explained that in the case of Sri Lanka, Portuguese, along with Sinhalese and Tamil, may have come together to form a type of pidgin unique to our country. When this pidgin was learned by the next generation of speakers as a first language, a new creole language emerged.

The mestiços adopted this pidgin version of Portuguese as their first language and the language evolved into a creole. When the Dutch took over from the Portuguese in the 17th century, they married many local women of Portuguese heritage. This was how the ‘Dutch Burgher’ community was formed. Though the Dutch were very powerful conquerors, their attempts to popularise their own language were futile. They had to learn Portuguese creole themselves to converse with their Creole-speaking wives and domestic helpers.

Ceylon Portuguese was a prominent language and the mother tongue of the Burgher communities, until the arrival of British colonisers at the end of the 18th century. According to Dr. Hugo Cardoso, a visiting linguist from the Centre for Linguistics at the University of Lisbon, after the British assumed control over the entire country, some steps were taken to properly study and document the language. Dr. Cardoso is currently conducting a project titled ‘Documentation of Sri Lankan Portuguese’ which is funded by the Endangered Languages Documentation Programme of The School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London.

Dr Cardoso further mentioned that Ceylon Portuguese was also used by the Wesleyan missionaries, who produced some literature in the language to spread their faith among the dominantly Catholic Burgher community.

The earliest analyses of the language were done in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and they consisted of a few dictionaries. There were even periodicals in Ceylon Portuguese and also collections of oral traditions. This scholarship was only resumed in the 1970s, when modern fieldwork-based research began focusing on the language. Ian R. Smith’s thesis, published in 1978, was an important milestone in SLPC studies and his research surveyed the Creole-speaking people of the Batticaloa area.

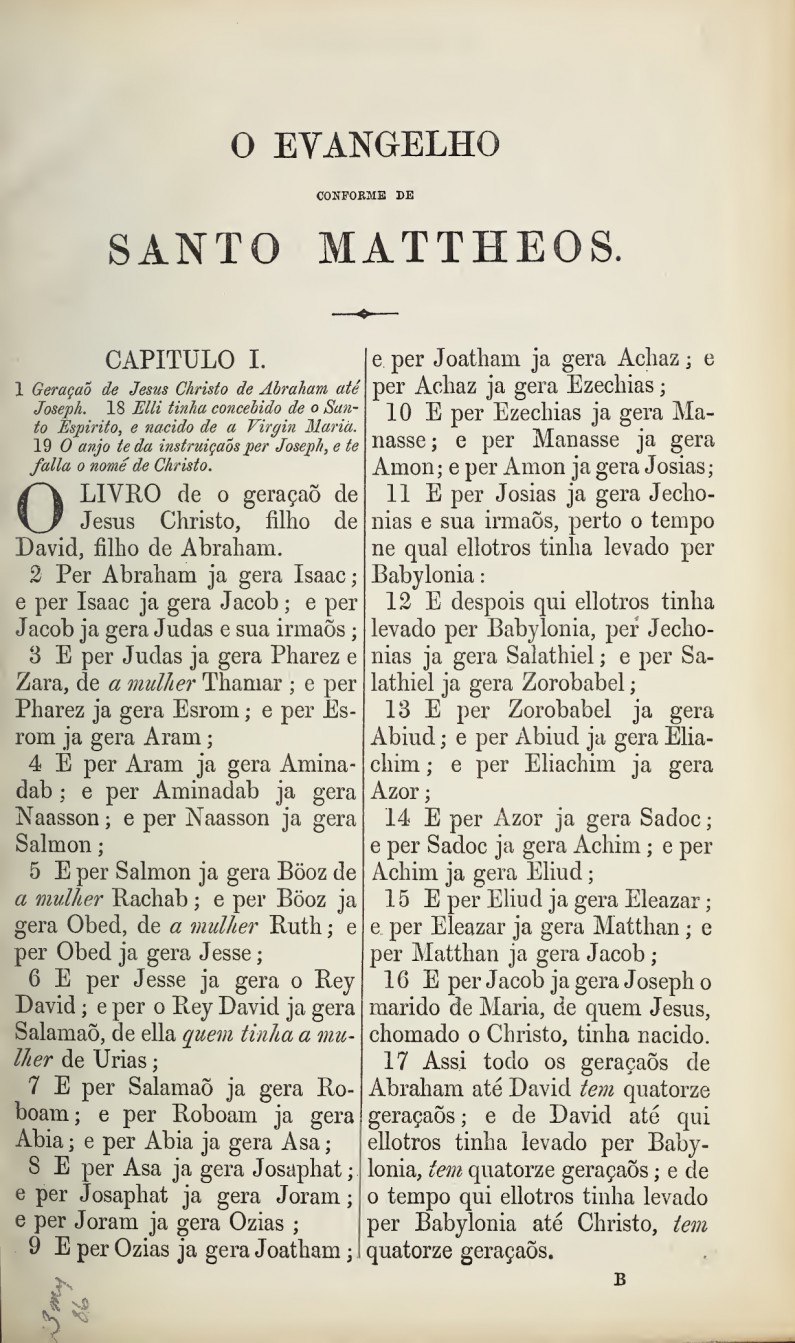

A Ceylon Portuguese translation of the book of Matthew from the Bible that was published in London in 1851. Image courtesy Hugo Cardoso

Dr. Cardoso also told Roar that SLPC is so different from European Portuguese that he had to learn it almost from the very basics. Conversely, he emphasises that a native creole speaker would find the same challenge if he or she were to visit Portugal.

Today, linguists consider SLPC an important creole in Asia, because historically, it was one of the most widely-spoken Portuguese-based creoles in Asia as well as the one with the most written records. Dr. Cardoso also stated that SLPC attracts attention owing to important traditions such as the music and dance associated with the community. From an academic and linguistic perspective, SLPC is interesting because its grammar has been influenced to an unusually large extent by Tamil, especially in the case of the East. In the process, it developed linguistic characteristics that are relatively rare in creole languages. Even after the departure of the Portuguese colonisers, SLPC still flourished across the country until at least the middle of the 19th century.

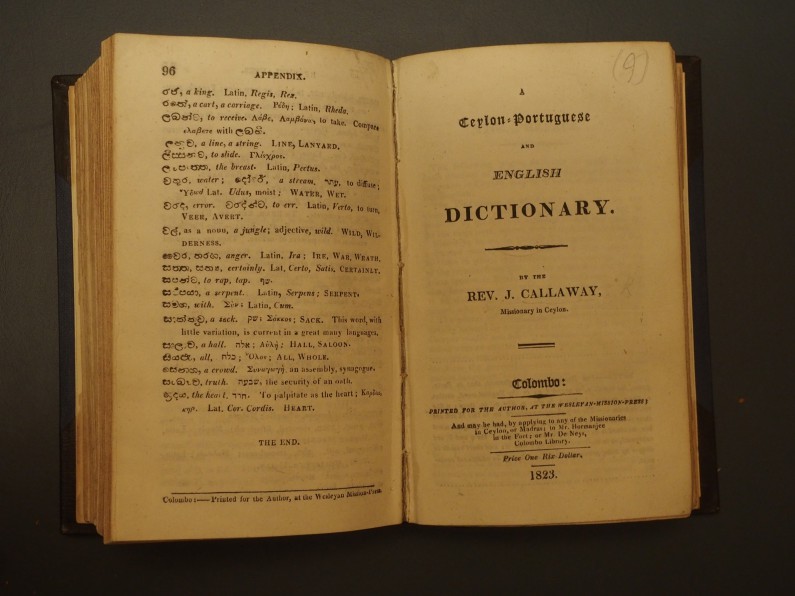

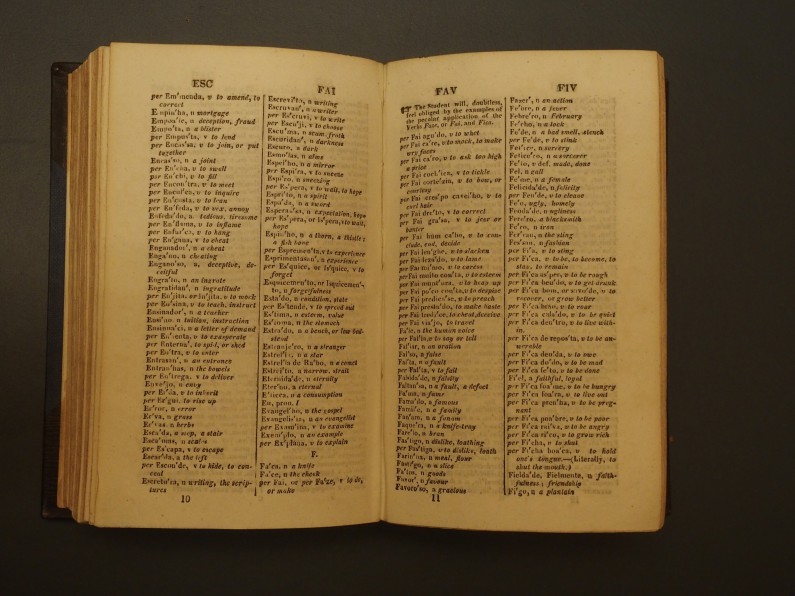

This dictionary was a part of the documentation of the Ceylon Portuguese undertaken by the British. Image courtesy Hugo Cardoso

Nowadays, the language is on the decline. Tamil is more widely spoken among the Burgher communities of the East, where most SLPC speakers reside. A few creole-speakers have migrated to Colombo as well as to other parts of Sri Lanka, and some have migrated overseas. Dr. Cardoso says the current number of speakers is uncertain. He added that he will be conducting a survey among these communities in September to ascertain the exact number of speakers, as a necessary step to preserve this unique language.

“There is a clear decline in the transmission of the language to the younger generations,” explained Dr. Cardoso. “Therefore, we would like to assist community efforts to preserve both the language and other manifestations of Portuguese Burgher culture.”

There are several reasons for this decline. Currently, SLPC is mostly used within the household and community, while Tamil is dominant in public and official settings. Unlike in the past, it is currently mostly an oral language with no well-defined writing system, even though some written records have been produced in recent years. Many families also feel the pressure to raise their children to speak Tamil, English, or Sinhala in fear that they will not achieve a good command of these languages by the time they start formal education.

A Ceylon-Portuguese and English Dictionary by Rev. J. Callaway published in 1823. Image courtesy Hugo Cardoso

We should remain hopeful that steps will continue to be taken to facilitate the transmission of SLPC through the written medium and to popularise it among younger generations. These steps are necessary to preserve a language that may have its roots in Portuguese but is also uniquely Sri Lankan.