Citizen protests began picking up steam in Sri Lanka late last year, in response to a foreign exchange crisis that led to a scarcity of domestic gas and fuel, impacting homes and transportation, and heralding sweeping power cuts. But what began as simple protests in neighbourhoods coalesced by the end of March into a popular movement that became known as the ‘aragalaya’ — or the struggle — under the banner ‘#GoHomeGota2022’ (in reference to then-President Gotabaya Rajapaksa) and a wider and deeper call to change corrupt and inefficient political systems that were identified as the cause for the mismanagement that had led to the situation the country was grappling with.

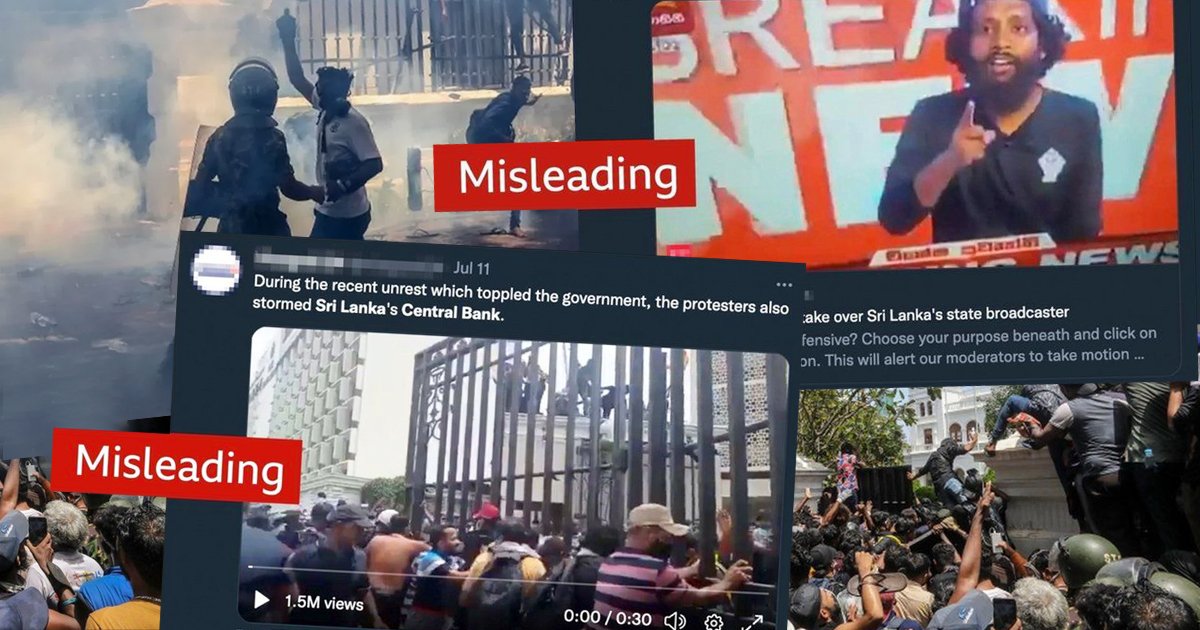

Unlike other popular movements before, this ‘aragalaya’ was documented and shared online at a scale never seen before as a result of the widespread use of technology and mobile devices. On the flip side, as with any large influx of information, multiple narratives and counter-narratives also began to proliferate online.

“Looking at the growth of the public discourse which led to the mass protests, it was organic,” Asela Waidyalankara, a cyber security advisor and educator told Roar Media. “The discontent, the displeasure, and the growth were organic.”

This did not, however, necessarily mean everyone was on the same page.

“From the early days, the protests were contentious as opinions within Lankan society were polarised along ideological and nationalist lines. While all (or almost all) citizens shared the same suffering, there was no consensus about the causes or attributability of the economic crisis,” media analyst Nalaka Gunawardene said, pointing out that some, in blind support of the Rajapaksa regime, had lived in denial for weeks into the aragalaya — with some others still doing that.

“In such a setting, it wasn’t surprising to see counter-narratives — fully allowed in democratic discourse — emerging, as well as more insidious attempts being made to discredit the protest movement and its key personalities. Disinformation in all its various forms was deployed as part of this process,” he told Roar Media.

Dissing The Narrative With Disinformation

Among the narratives being battled out during the months that the aragalaya was at its peak, most were about the protestors and protest sites.

Two of the earliest instances were smear campaigns denouncing protestors as “extremists” and levelling the accusation that protest sites were filled with drugs and used condoms. Later, the presence of fake accounts spinning anti-aragalaya and/or pro-government commentary also sprang up.

“I have yet to analyse all the multitudinous material generated by the protest movement and counter-narratives. But some trends became clear by late April,” Gunawardene said.

One trend, according to Gunarwardene, was releasing misleading information— in most cases blatant lies and in others, misleading information — to damage the reputation of key protest personalities, including several professionals supporting the movement. For example, during the course of the movement, there were several ‘statements’ circulating among social media platforms as being made by Saliya Peiris, the president of the Bar Association of Sri Lanka (BASL). The BASL President had to clarify and deny such statements on multiple occasions.

Such misleading or contradictory reports were created with the intention of confusing the masses and the wider public. According to Gunawardene, these campaigns, created in large numbers, sought to weaken the protest narratives by flooding social media with various diversions.

Another observed trend was the attempt at ‘hijacking’ key hashtags and conversations revolving around them.

False stories were planted in journalistic circles that spread fear, panic, and contempt about protesters in established media, Gunawardene added, stating that “some ‘jumped’ over to social media by uncritical sharing, which is the definition of misinformation.”

Sanjana Hattotuwa, a research fellow at The Disinformation Project, noted that there were indications of troll accounts being used during this time. “What you find in Sri Lanka is a troll – a set of accounts controlled by one entity – across the board. This was not only on Twitter but on Facebook as well,” he explained.

Both Gunawardene and Hattotuwa called the attacks “sophisticated” and “systematic” — Gunawardene noted: “While digital and web technologies were used to deploy and deliver these counter-campaigns, manipulation of public opinion required strategy, creativity, determination and staying power – all of which are intrinsically human attributes.”

“Alternate narratives wouldn’t have been popular if people didn’t believe them. By the time [these campaigns] were done, [the results were] nowhere as compared to a similar campaign in 2019. But I do not dismiss [the magnitude and skill] of what was done,” Hattotuwa added.

The Power Of The People

How successful were these counterattacks and narratives in challenging what was manifestly a people’s movement? “It’s, unfortunately, a little difficult for troll accounts, bot accounts, and fake profiles to counter pure organic growth, and that’s where I think [these attempts] fell flat,” noted Waidyalankara, adding: “While there were attempts to introduce and amplify dissent within the movement, that did not succeed because the social pressure was so high and the organic growth of the movement was so supreme.”

Hattotuwa agreed on the same, pointing out that dissent was more visible on platforms such as Twitter because they had a smaller Sri Lankan demographic, and therefore would highlight even minor dissent. On the more crowded platforms such as Facebook, the dissenting narratives against the aragalaya were almost buried.

However, there’s no clear-cut ‘success’ or ‘failure’ in these matters, pointed out Gunawardene. “There were many and varied counter-narrative and discrediting attempts, and they had varying degrees of effectiveness. Some people among the 11 million or so Lankans now online would have uncritically believed and further disseminated these manipulations,” he said, “and others would have seen through it or at least been suspicious of it.”.

Sri Lanka’s History Of Disinformation

Hattotuwa said this was not the first time narratives have been changed through the employment of disinformation; rather, it’s been present for years.

“Sri Lankan society has no inoculation against disinformation,” he pointed out, adding that, however, in the case of #GoHomeGota2022 specifically, there were people identifying specific instances, people, accounts, etc. “There was a broader discussion on the topic; I’ve never seen that kind of discussion happen before,” he said.

Gunawardene, as someone who follows both established and digital media, noted several instances: “I had earlier seen a surge in such attempts during the abortive coup of October – December 2018, as well as during presidential elections of November 2019 and general elections of August 2020.”

Sri Lanka’s disinformation problem goes beyond a simple case of narratives being manipulated in a few select instances, Hattotuwa explained, calling it ‘structural disinformation’— the result of culture is built on values, “like misogyny, or toxic masculinity, or racism [which are] already severely harming democracy.”

Getting Rid Of The Trash

Attorney-at-Law and Constitutional Lawyer Gehan Gunatilleke, speaking on the legalities of such matters, opined that he thought a legal (particularly a criminal justice) approach may not be an appropriate way of dealing with disinformation of this nature. “It may be best to confine legal interventions to cases of incitement to violence, and discrediting of protests may not meet this threshold,” he said, adding that the challenge here is that state actors and political actors are often behind such disinformation campaigns.

“There are other ways of combating such disinformation, and counter-messaging may be one of the options. But counter-messaging is quite difficult when you’re up against the state. So, in these circumstances, legal interventions are in any event futile. The only option is to counter the narrative through credible voices,” he noted.

Hattotuwa opined that the conversation for a solution would be around media literacy, which is an individual’s task and responsibility. “There is a whole cornucopia of factors that you can address with media literacy, individual approach, or movements,” he said.

However, he also noted that what happened with #GoHomeGota2022 would be a good learning opportunity that is yet underutilised. “We need to reflect in a more concerted manner about what we talked about and identified during the Aragalaya,” he said. “The aragalaya is a teachable movement – it taught us about how we’re being manipulated in real-time. There were a lot of things happening that I really haven’t seen people reflect on. A really good place to start would be to talk about what we learned and studied during those months.”

Gunawardene concluded by saying, “Sri Lanka’s protest movement of 2022 was a rallying call for social justice, accountability and better governance. We have to wait for a few years to assess how much the protest narratives of this year’s aragalaya ultimately shape Lankans’ public opinion, public memory and voter behaviour at the next elections (whenever they might be held). In that sense, the struggle for Lankan minds and hearts is far from over.”

.jpg?w=600)

.jpg?w=600)

.png?w=600)