In Mallayarkattu, a remote, dusty village nestled between Ampara and Batticaloa, *Thiru, a father of two, carefully rides his bicycle to his cousin’s house. The ride is a short one, but Thiru remains cautious. He keeps his movements steady, his grip firm, and his eyes focused on his periphery. He is on the lookout for elephants. It has only been a month since his 18-year- old son was killed by one of these giants. Like Thiru, his son was on his way to visit a relative.

Over the years, residents of the area have employed scare tactics—like making loud noises—to keep the animals at bay. Although effective at first, the elephants soon realise that there is no danger posed by these disorienting sounds. Armed with this information, they return, desperately searching for something they can eat. The people of the village stay frozen while the animals raid their homes, stealing monthly supplies of food. Food that they cannot afford to replace.

Clouded by rage, a resident of the village may decide to kill the animal, in an ill-advised attempt to exact revenge. He may hide explosives—locally called hakka patas—inside a watermelon, and leave it out as bait for the next hungry elephant to bite into.

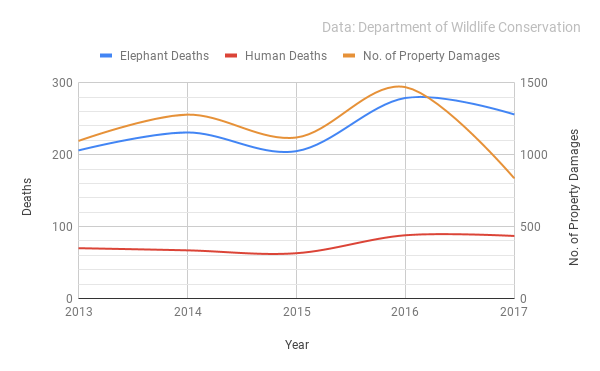

The conflict between humans and elephants has been an ongoing issue facing Sri Lanka’s rural and semi-urban areas. According to the Department of Wildlife Conservation, it has resulted in 87 human deaths, 256 elephant deaths, and over 800 damaged properties in 2017 alone. Two children were killed in Mahiyanganaya on November 23rd, crushed by an elephant that attacked their home.

As the death toll mounts, widely implemented, effective solutions are long overdue.

Although there have been fluctuations in statistics relating to the conflict, the numbers have not significantly changed since 2013, despite efforts from many organisations working hard to mitigate these losses.

According to Dr. Pruthuviraj Fernando, an elephant expert and scientist who has worked in many countries to provide long-term solutions to this conflict, “What is really special about Sri Lanka is that people have a very close association with elephants. Sri Lankan culture and religion creates a background that is conducive to co-existence.” Considering this information, it is surprising that Sri Lanka has not yet managed to execute a viable solution for the human-elephant conflict over the last decade.

One reason for this is that many parties working towards conservation seem to be doing so in ways that are tangential to one another. Legislative solutions to the problem seek to implement short term fixes to pacify the public. This often results in the implementation of plans that have a high chance of failure in the long term.

According to Manori Gunewardene — Director of Environmental Foundation Ltd (EFL), an organization dedicated to protecting the environment through legal and scientific means — the tendency to blame affected villagers without understanding the complexity of the situation can also be harmful.“There are conservationists who speak from a position of knowledge, and then there are very well meaning people in the conservation community who speak from emotion,” she says. “These people are often very far removed from the ground reality, and tend to be more fixated on where to place the blame rather than how to solve the problem.”

Repeating Old Mistakes

On the 18th of July 2018, the government proposed a two-year solution aimed at ending the human-elephant conflict. The plan was approved by the cabinet, but due to the current political situation in Sri Lanka, conservationists remain unsure if it will be implemented or not. Despite this, the methods recommended in the plan are not new, and worth discussing.

The main objective of this plan is to construct a further 2,500 km of electric fencing to designated “protected areas” for elephants which comprises of the the country’s national reserves. These protected areas sit on 18% of Sri Lanka’s landscape, and the elephants that live outside of them will be driven into them. To ensure that the elephants remain within these confinements, it is proposed that 3,500 Civil Defence personnel be stationed at the border and armed with high-powered Chinese rifles.

The methods proposed in this plan have been met with criticism from those in the conservation community, particularly because they have failed in the past. “Ever since the 1950s, the Department of Wildlife believed they could drive wild elephants into protected areas,” says Rohan Wijesinha , — member of the Human Elephant Conflict (HEC) Committee of the Wildlife And Nature Protection Society (WNPS) and Chairperson of Federation of Environmental Organization (FEO) — “ The problem was, that they didn’t really know how many elephants they were dealing with. If we take current statistics, 70% of Sri Lanka’s elephants live outside protected areas, in 62% of the country’s landscape.”

At present, there are not enough resources inside protected areas to support the number of elephants. Many of them are already at capacity, or unable to support the number of elephants they already have. This year, it was found that 54% of calves in Yala die at infancy due to malnutrition caused by lack of resources.

Many conservationists do agree that at present, electric fencing is the best way to separate humans and elephants. But it is important to locate them in the correct place. For example, the electric fencing set up at Yala is incorrectly located on administrative posts. This fence divides the Department of Wildlife land from forest land, although they are both protected areas.

“The natural course for elephants that run out of food on one side of the fence would be to cross over to the other protected areas, but due to the fence they are forced to go into neighbouring villages,” says Wijesinha. “For fences to work, they must be located on ecological boundaries.”

To carry out this plan, the department will be tapping into the wildlife preservation fund, which currently has reserves of about Rs. 5 billion. This money is projected to be spent in two years, with a large chunk of it going towards purchasing weaponry and the deployment of civil defense forces in affected areas. Wijesinha has addressed his concerns over this budgeting decision directly to those involved in this initiative.

“When I asked them why so much money was needed for guns, the response was that it is to fight poaching. I have two ethical problems there. The first being, are we really going to shoot people? I’m against poachers, but I still don’t think that’s a viable option. The second is if it’s not to shoot people, it is to shoot elephants, and I have a problem with that too”.

Community Participation: The Way Forward

“Conservation is the remit of the people on the ground, that is the only way it can be sustainable,” Gunewardene reiterates. Her mentor, Dr. Pruthuviraj Fernando, through his experience in working closely with communities in affected areas, has also found this to be true.

“People have suffered great losses due to elephants, and have very legitimate problems. They have had economic losses as well as prospect of death and injury. This can be addressed through community based fencing” says Fernando.

Community-based fences are electric fences that are put up by the people, enclosing specific areas that need protection. Farmers, for example, tend to erect them when they cultivate, and then remove them during harvest. This has been piloted in Sri Lanka and found to be successful when implemented.

Community based fencing is currently one of the most effective ways of mitigating this conflict. Photo credit: www.projectelephant.org.u

“Many times, when people support government legislature, it is because they aren’t aware of the consequences to the elephants,” says Fernando. “If you ask someone if they would like the animal to be taken away, of course they will say yes, especially if they believe the animal will be okay.”

With community-based fencing, local residents are given ownership of the fences, although the initial implementation costs are paid for. With this method, it was found that people were more likely to invest time in maintaining the fences.

Many conservationists are calling for this method to be adopted by legislature, and are against the proposed legislative solutions. Speaking on the matter, Fernando said, “If [the government] does implement this new proposal, I would suggest they first try it out on a sample of land, and see if it works. If it doesn’t then at least the damage done would not be as grave, and there will be an opportunity to fix it.”

This method of fencing has the potential to be very effective, if the fences are located in the correct place. The debate over where to locate the fences has also caused some contention in the conservation community.

“Science says that you can draw the line in the best possible scenario, so there has to be a bit of give and take. The contention is that there are scientists saying that if you solve 80% of the problem we are happy, and people who want to conserve the elephants say they want every single elephant saved,” says Gunewardene.

From her experience, she has found that it is very difficult to provide solutions that have a 100% success rate. In order to focus on long-term effectivity, compromises have to be made. This involves understanding the nuances of not only the conflict itself, but its proposed solutions.

“What often gets lost in the public outcry generated by an issue such as this is its complexity, and an understanding of that complexity is vital when we’re thinking about solutions,” said Gunewardene. “If you have to make a very hard choice between saving a species and saving an animal, I would chose the species.”