Brace yourselves: we’re in for a rough ride. Despite what climate change nay-sayers may claim, the truth is that the climate is, without any doubt, changing… for the worse – and we don’t have to look beyond the Indian Ocean for proof. According to latest research, the warming of the Indian Ocean has been taking place at a faster pace in comparison to other oceans of the world. This has resulted in a drastic reduction of phytoplankton in the Indian Ocean, and the weakening of the monsoon. This means trouble, not just for Sri Lanka, but the entire South Asian region.

The Issue

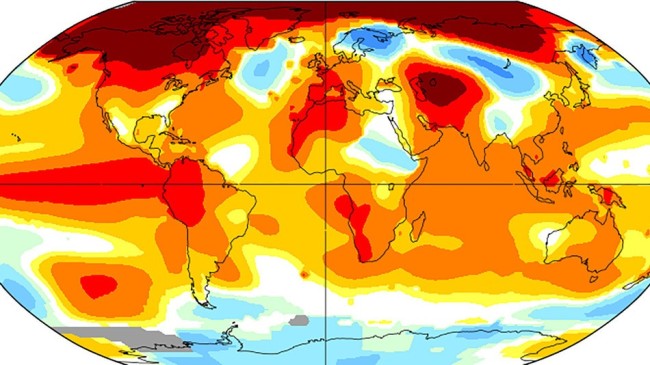

A warming Indian Ocean can spell drastic weather fluctuations for Sri Lanka. Image credit newsinfo.inquirer.net

Over the last century, the Indian Ocean has been warming at a faster rate than other oceans of the world, with “a rapid and continuous basin-wide warming (taking place) since 1950,” climate scientist Dr. Roxy Mathew Koll told Roar. For that matter, the change measured is between 0.7 to 1.2°C, while the global mean change is 0.8°C. Dr. Koll explains that the Indian Ocean has warmed two to three times faster in comparison to the central tropical Pacific: the warming can be partly attributed to increased levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, in addition to the Indian Ocean being relatively landlocked in the north, unlike the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans.

Dr. Koll added that as a result, “the ocean circulation is restricted from flushing out the heat to the poles,” and therefore the heat pile-up persists for a longer time. In addition, heat in the Indian Ocean accumulates through “a modified atmospheric circulation” due to El Nino-like conditions in the Pacific. He observed that “the magnitude and frequency of El Ninos have gone up in the recent decades, and so has the ocean temperatures in the Indian ocean.”

What This Means

Dr. Koll has identified two main problems: a temperamental monsoon, and an affected food web.

Where the monsoon is concerned, he explained that while there is an increase of moisture in the atmosphere, the monsoon winds transporting moisture is weakened, spelling trouble for the South Asian subcontinent in many ways. On one hand, this will result in a decrease in rains over central South Asia, but on the other hand, equatorial regions will see an increase in rainfall. He added that “though we have not specifically focused on the rainfall changes over Sri Lanka, we see a slight increase in rainfall due to its proximity to the region where the warming has occurred.”

What this means is that we’re all in for bipolar weather: the warmer climate has ensured that the atmosphere can hold moisture for a longer period, which will result in long dry spells interspersed with extreme rainfall.

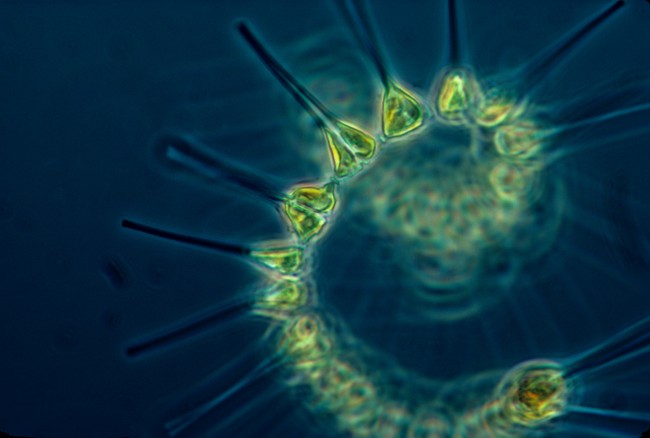

There has already been a 20% fall in phytoplankton, which form the base of the marine food chain. Image Credit: Wikipedia

The warming of the Indian Ocean has also affected the marine food-web, on which many countries in the region are heavily dependent. There has been a 20% decline in phytoplankton, microscopic plants where are the basic building blocks for the food web. With an integral part of the food chain affected, there could be a chain reaction on other marine life, adding further stress to the marine ecosystem. To a great extent, this also threatens food security.

How This Will Affect Food Security in the Future

The effects will be seen on both land and sea. Rainfall changes will have an immense impact on agriculture. Central South Asia will see a reduction in rainfall, while Sri Lanka will experience a predicted increase in rainfall. Either way, the reductions and increase will result in a severe blow to the agricultural industry, which is heavily dependent on rainfall.

Indian ocean warming has had, and will continue to have, an adverse impact on marine life. Image Credit: cosmosmagazine.com

Similarly, the fishing industry will take a hit. Dr. Koll explained that a decline in marine phytoplankton was observed in the western Indian Ocean, ranging from the Kenya-Somalia coast to the Gulf coast, to the south of the Indian peninsula around Sri Lanka, potentially affecting the fish and other marine species in the region. “Most fish species have a very narrow range of optimum temperatures related to their metabolism… even a change of 1°C may affect their distribution and life cycle,” Dr. Koll explained, adding that it could result in fish migrating to cooler waters, dying out entirely, or getting affected by invasive species.

The Next Step

We can’t stop climate change this late in the day, but we can prepare for the worst. Dr. Koll suggests, where agriculture is concerned, cultivating crops which can withstand drought and flood conditions would help, in addition to a judicious usage of water, as well as the right methods of irrigation and water storage. Where fishing is concerned, he pointed out that commercial fisheries in the Indian Ocean isn’t regulated. “Regulating the total allowable catches through a proper allocation system maximises sustainable yields, helps the fish and marine ecosystem to adapt to climate impacts, and also reduces greenhouse gas emissions by fishing boats,” Dr. Koll said.

In Perspective

Global average temperature anomalies for January 2016. Image Credit: NASA GISS

Going by reports, as it stands, Sri Lanka has seen a 7% reduction in rainfall over the past five decades, prompted by the very warming which will potentially increase rainfall. The temperatures in Colombo, Sri Lanka was also 1.2°C higher in 2015, in comparison to the other years, while globally NASA has noted that January 2016 was the warmest January ever recorded. With the current prevailing El-Niño conditions coming to a gradual close, there are also predictions of it being replaced by an equally strong La-Niña. It doesn’t look like the climate is about to catch a break anytime soon so we had best be prepared.