You can say that there are two types of people in this world: the coffee-addicts and the tea-enthusiasts. Upheld by some sugary pride, Sri Lankans most likely lean towards the latter; for the island’s tea is regarded as one of the world’s best. A cheerful slurp of warm tea during the day over conversation or cake is quite an adamant routine we resort to for satiation. Also, let’s not forget the golden rule author George Orwell applied for preparing tea in his essay titled, A Nice Cup of Tea, in which he asserts: “First of all, one should use Indian or Ceylonese tea.”

Tea-pluckers busy picking leaves at a tea plantation in Nuwara Eliya. Image courtesy writer

Thus remains a curiosity piqued. In order to perceive the artful elements responsible for the taste in Ceylon tea, prompting Orwell to even regard it exemplary, we headed to the headquarters of the largest tea exporters in Sri Lanka, Akbar Brothers, at Maradana. As we stepped into the tea-tasting laboratory, a heavily pleasant aroma filled our noses. One thing was clear: tea for tasting and inspection was currently in the state of preparation. But before that, we had the opportunity to meet Executive Director Joseph Sinniah, who gave us a crash course on the origin of tea and its processing.

Etymology And History

The legendary tales of the emerald shrub scientifically known as Camellia sinensis, a name christened by the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus, are countless. However, the most familiar one goes back to China. Around 5,000 years ago, little were Emperor Shen Nong’s servants aware of how this plant would graduate to become a much-yearned beverage, believed to vanquish all discomforts. While following his mandate to boil the water before drinking, the dried leaves of a camellia bush, that summer day, were blown into the brewing pot. Once this was served, not only was the Emperor’s taste-buds charmed, but his interest sharpened towards the distinct liquid. Thereafter, tea struck him as therapeutic, although simply born out of an accident, or so the story claims.

Tcha or tea, now the national drink of China, was introduced to the British in the 17th century and subsequently, sources vouch, the plant was brought to Ceylon in 1824 by the Englishmen. Thus, the island is, at all times, indebted to James Taylor, of Scottish origin, who had immensely contributed to the expansion in tea trading— starting on a spread of just 19 acres at the Loolecondera estate during his stay in Kandy, and continuing until his death.

Miniature versions of the machinery/equipment used for the manufacturing of tea in factories. Image courtesy writer

Decades later, the inaugural public tea auction was carried out in Colombo in 1883, and the Colombo Tea-Traders’ Association was formed in 1894. Despite modest beginnings during the early stages, today, around 6.5 million kilograms of tea are sold each week in Sri Lanka, making it the single largest tea auction in the world. The contributions of these organisations have also tremendously sustained in steering new ventures for the trading of Ceylon Tea.

Tea Cultivation In Sri Lanka And Beyond

A variety of tea samples await evaluation before the weekly Colombo Tea Auction, which takes place every Tuesday and Wednesday morning at Nawam Mawatha. Image courtesy writer

With an expanding market, Sri Lanka’s tea trade began to swell by the late 19th century, alongside competition from other countries, including China. Thereon, tea cultivation rapidly burgeoned in different parts of the globe in countries such as Nepal, Bangladesh, Indonesia, Kenya, India, Bolivia, and the less known Papua New Guinea. Given the ideal rainfall, slopes of soil, and altitude in these countries, a sterling quality of tea is evident year around.

Tea hills, well-known for their high-grown character, seen under a cloak of mist at Nuwara Eliya, Sri Lanka. Image courtesy writer

As Sri Lanka rests in the tropics of the northern hemisphere, the central and southern regions of the island are where most of the tea is grown. Being the first to receive the ‘Ozone Friendly Tea’ label, these teas are classified into three key groups according to location. While high-grown (Nuwara Eliya, Hatton) teas provide excellent aroma and a dark colour, the mid-grown (Kandy, Nawalapitiya) teas come with sound flavour and take on a mild darkness. The low-grown (Matara) teas, on the other hand, are light in colour with flavours mellow and soft, often less tangy.

The varieties of tea available to consumer today range from green tea, flavoured and herbal blends, black tea, oolong tea and white tea; with green tea maintaining a predominant value in the industry, globally.

The Art of Tea-Tasting: The Black Tea Method

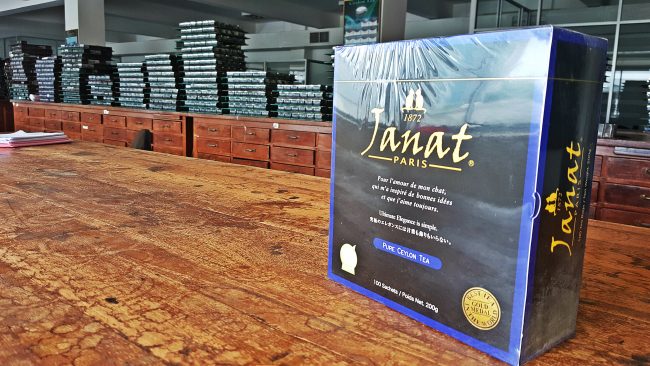

Janat, a sophisticated French tea brand, mainly purchases its teas from Sri Lanka. Image courtesy writer

In 2014, Joseph Sinniah was presented the ‘World’s Best Tea Blender’ award by the eminent French international magazine, The Magazine. This is recorded as a first for Sri Lanka. Such a figure recognised for his expertise at the tasting laboratory, we thought, would be fitting to give us an inclusive study on tea-tasting.

Tea leaf samples of different varieties, post-manufacturing. Image courtesy writer

To achieve precision of the signature character in Ceylon tea, which holds a reputation worldwide, lies in the skilled practice of a tea-taster. Tea-tasting, we were told, essentially involves the process of determining whether the quality of a specific tea sample is adequate for consumption. Why is this important? “The plant’s voyage from tea garden to processed batch is a lengthy one. Chances are high to vary in taste and tea-tasting is one workable aspect in assisting quality compliance,” Sinniah explained. This process, he went on to add, gives the tea drinker his/her choice to pick what delights their palate, and many tea consumers are just as able to track a difference in the drink, if any.

When we arrived at the tea-tasting table, startling to see was how tea-leaves had evolved into several shapes and sizes after the manufacturing process. Some leaves were scrunched up into little balls, while others like wires were twisted, and there were those crushed to powder, too. We were also informed of the taste receptors on the human tongue (sweet, salty, acidic, bitter, umami), as we prepared to taste our tea.

1. What To Keep In Mind

The infused brews in each porcelain bowl are left to wait for 3-5 minutes for the flavours to develop. Image courtesy writer

- Plastic and/or disposable cups are avoided; instead, authentic white porcelain (a pot, bowl, lid) would do to help with gauging colours and depth, and are also good at retaining the aromas.

- For the brewing of black tea, it is advised that freshly drawn water go in a kettle with a larger capacity.

- The boiled water must be set aside for 5 seconds before pouring into the porcelain vessel.

- Brewing time should be between 3-5 minutes to achieve a balance in the flavour and strength.

- The right amount of tea for the infusion should be between 2-2.5 grams.

- After each slurp, the liquor should not be swallowed, but spat out, in this case into a spittoon, to prevent the flavour from dulling the other flavours yet to be tasted.

2. The Process

Warm infused liquid being poured from the pot to the bowl. Image courtesy writer

- On a table, tucked next to a line of porcelain pots and bowls, are various dry leaf samples in uniformly shaped metal containers coded by the tasters. Before brewing, each dry leaf is given a visual analysis, as a starting point. The taster does this to judge:

Size/Shape – Broken leaves exude bitterness which is indicative of low quality.

Colour – Subject to change according to type of tea.

Moisture content – Tea leaves should be brittle. Depending on the type of tea, this may take the form of powder.

Texture – Includes the ‘tips’ or buds.

- Next, the infusions of coded samples are poured into the boiling water. This involves the distribution of 2 grams of tea into a ½ bowl of water. The container is covered with a lid and set aside for about 3-5 minutes for the flavours to evolve, a process known as steeping. This is often overlooked in domestic kitchens mainly due to impatience, Sinniah pointed out.

- Once the infusions are poured into the bowls, the infused remains of the leaf are presented on the lids for visual inspection. What is determined here is the colour, consistency, and aroma of the leaf.

- Afterwards, the infused liquor is observed. This is a critical stage, and tasters must pay attention to:

Clarity – The fluid should ideally provide a strong tint.

Shine – Traditionally, a glossy radiance is sought, as this suggests a good amount of tea oils has been diffused in the infusion, and the brew, well-processed.

Aroma – Is it smoky or stale? Does the aroma linger in the bowl after the drink? If it’s fresh tea, it most likely would.

Colour – Subject to change according to type of tea.

- Eventually, a silver ladle is sunk into the infusion and brought to the taster’s mouth. He/she sips a generous amount of the liquor while making a noisy sucking sound. This is required and not considered a bad habit, as it allows the infusion to merge with oxygen liberally pushing through the taste-receptors, bringing out the full range of flavour. The tea is then let to sit on the tongue and slide to all sides. Although subjective in most cases, here, the taster looks for answers in the subtleties led by first impressions. (Is it refreshing? Does the taste linger? Any signs of astringency?)

3. Aftertaste And Terminology

Executive Director and professional tea taster, Joseph Sinniah, takes a sip of the liquor sample at the tea-tasting laboratory. Image courtesy writer

Since the sessions are conducted by independent tasters, who, with their own expressions arrive at different conclusions, the standard sought is often a silky shine of golden brown, which out to provide a sense of refreshment when sniffed. However, we learned that during blending, this too can vary as per the client’s need. According to Sinniah, the client’s requests are a priority; everything else comes after.

If you’re still curious, you could check out this list of the frequent terms used by tea tasters at the laboratory to describe the liquor once a parade of flavours is perceived, which makes it an altogether surprising experience for the palate.

Health Benefits

Different infusions ready for tasting are arranged according to key groups. What we see here on the tray are the high-grown, mid-grown and the low-grown teas, in that order. The colour variants are also visible. Image courtesy writer

Over the years, scientific studies have declared the regular intake of tea makes it a healthier beverage than most others. The rich antioxidants available in our tea are approximately ten times the amount existent in vegetables and fruits. Drinking more tea is also believed to result in the prevention of cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases as well as gum diseases.

That said, apart from promoting physical well-being, green tea holds commendable cosmetic benefits. It is advised that utilising green tea in beauty masks for skin enhancements would stave off aging of skin thanks to the antioxidants, a major nourishing component found in tea.

All these added benefits aside, in a country like Sri Lanka, a classic cuppa shall continue to be the drink of the masses, savoured between smiles, while a wispy aroma prods the air.