The first draft of the proposed 20th Amendment to the Constitution is here and to no one’s surprise. Although the first version of the 20th Amendment was introduced, drafted, and billed in Parliament by the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna in 2018, the new government’s version promotes and parades entirely new reforms.

Once passed, these reforms will become the 20th instance where the country’s constitution was amended by an empowered government, as a result of fulfilling a public mandate. The full draft of the amendment as gazetted can be read here.

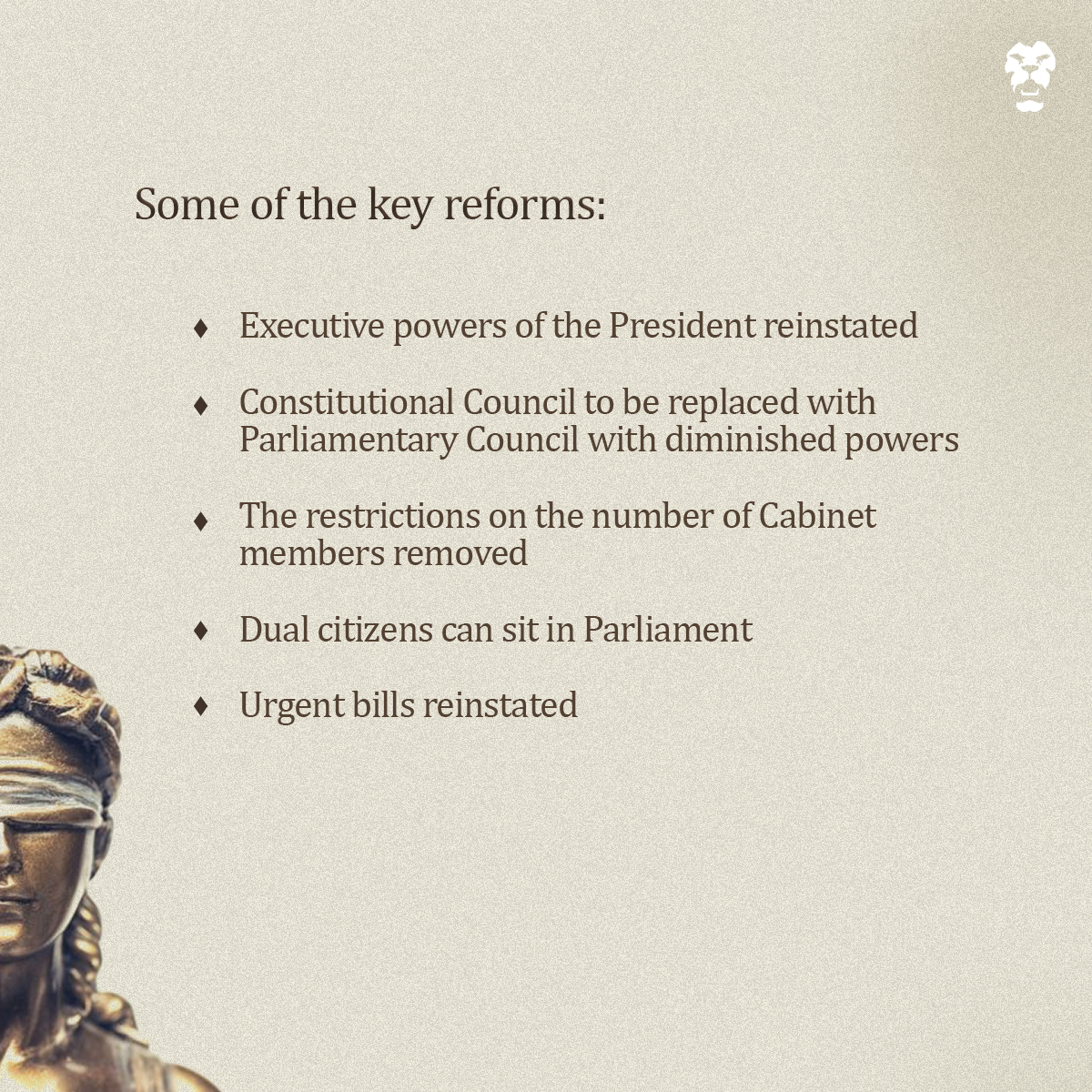

The following is an overview of some of the proposed reforms:

Enter The Executive

While almost all reforms proposed in the draft to the 20th Amendment are noteworthy, reinstating the all-powerful executive powers of the president instantaneously becomes the most highlighted.

The 20th Amendment will restore all executive powers of the president, which were scaled down by the 19th Amendment to the Constitution by the previous government back in 2015.

The age of a person qualified to be elected to office as President, as dictated by the 1978 Constitution, was 30. This was increased to 35 under the 19th Amendment, only to be lowered to 30 again under the 20A.

It will also lift restrictions on the number of cabinet members and junior ministers who can be appointed.

Provisions relating to this as per the 19th Amendment, which declared that the president must seek the advice of the prime minister prior to making appointments, have also been removed. The president will now be able to exercise these powers on his own accord.

Article 44. (1) “The President shall, from time to time, in consultation with the Prime Minister, where he considers such consultation to be necessary –

(a) determine the number of Ministers of the Cabinet of Ministers and the Ministries and the assignment of subjects and functions to such Ministers; and

(b) appoint from among the Members of Parliament, Ministers to be in charge of the Ministries so determined.”

The 19th Amendment also repealed Article 35 of the Constitution, which provided immunity to the president from class-action lawsuits and replaced it with limited immunity. This, too, has been abolished — giving full immunity to the president.

Article 35. (1) While any person holds office as President, no proceedings shall be instituted or continued against him in any court or tribunal in respect of anything done or omitted to be done by him either in his official or private capacity.

(2) Where provision is made by law limiting the time within which proceedings of any description may be brought against any person, the period of time during which such person holds the office of President shall not be taken into account in calculating any period of time prescribed by that law.

(3) The immunity conferred by the provisions of paragraph (1) of this Article shall not apply to any proceedings in any court in relation to the exercise of any power pertaining to any subject or function assigned to the President or remaining in his charge under paragraph (2) of Article 44 or to proceedings in the Supreme Court under paragraph

(2) of Article 129 or to proceedings in the Supreme Court under Article 130 (a) relating to the election of the President or the validity of a referendum or to proceedings in the Court of Appeal under Article 144 or in the Supreme Court, relating to the election of a Member of Parliament:

Provided that any such proceedings in relation to the exercise of any power pertaining to any such subject or function shall be instituted against the Attorney-General.”

Exit Constitutional Council

The proposed reforms will replace the Constitutional Council with a much weaker Parliamentary Council with diminished powers.

“Article 41A. (1) The Chairmen and members of the Commissions referred to in Schedule I to this Article and the persons to be appointed to the offices referred to in Part I and Part II of Schedule II to this Article shall be appointed to such Commissions and such offices by the President.

In making such appointments, the President shall seek the observations of a Parliamentary Council (hereinafter referred to as “the Council”)…”

The Constitutional Council, introduced under the 17th Amendment to the Constitution, was the body responsible for appointing members to independent commissions. It was eventually replaced with a different body (the same institution that will replace it under the 20A) in 2010. The Council was empowered after being reintroduced under the 19th Amendment with more powers and the addition of civil society members.

Its replacement — the Parliamentary Council — will consist of the Prime Minister, the Speaker, the Leader of the Opposition, a nominee of the Prime Minister and nominee of the Leader of the Opposition. The latter two must be Members of Parliament.

The three civil society members who held membership in the Constitutional Council will no longer continue to have their seats in the new Parliamentary Council’s composition.

Dual Citizenship

Furthermore, the proposed amendment seeks to allow dual citizens to sit in Parliament.

A citizen of Sri Lanka who is also a citizen of another country — a dual citizen — was disqualified from competing in elections and entering Parliament as per the 19th Amendment. However, the 20A will allow dual citizens to be elected to Parliament.

More Power To The President

Under the 19th Amendment, a parliament must remain in power for a four-and-a-half year term before the president can use executive powers to dissolve it. However, this will change under the 20A when the president obtains the power to dissolve or prorogue Parliament after one year of its election.

“Article 70 of the Constitution is hereby amended by the repeal of paragraph (1) of that Article, and the substitution therefor of the following paragraph:-

“(1) The President may, from time to time, by Proclamation summon, prorogue and dissolve Parliament:

Provided that –

(a) subject to the provisions of sub-paragraph (d), when a General Election has been held consequent upon a dissolution of Parliament by the President, the President shall not thereafter dissolve Parliament until the expiration of a period of one year from the date of such General Election, unless Parliament by resolution…”

The president will obtain superior authority over the appointment of independent commission members, including the Elections Commission, the Human Rights Commission and five other similar bodies.

A majority of the independent commissions have survived under the 20A:

- Election Commission

- Public Services Commission

- National Police Commission

- Human Rights Commission

- Commission to Investigate Allegations of Bribery or Corruption

- Finance Commission

- Delimitation Commission

However, the Audit Service Commission and the National Procurement Commission will be abolished.

“Article 107 of the Constitution is hereby amended by the repeal of paragraph (1) of that Article and the substitution therefor of the following paragraph:-

“(1) The Chief Justice, the President of the Court of Appeal and every other Judge of the Supreme Court and the Court of Appeal shall be appointed by the President by Warrant under his hand.”.

The president will further retain powers to appoint the Chief Justice and the judges of the Supreme Court, the President and judges of the Court of Appeal, the members of the Judicial Service Commission with the exception of its Chairperson, the Attorney General, the Auditor General, the Parliamentary Commission for Administration (Ombudsman), and the Secretary-General of Parliament.

The president did not have the power to make these appointments under the 19th Amendment, unless they were approved by the Constitutional Council.

The appointment of the Chief Justice and the two most senior judges of the Supreme Court were made by the Judicial Service Commission under the 19th Amendment.

Urgent Bills

Another step done away with under the 19th Amendment that is making its reappearance is the parliamentary urgent bills.

Accordingly, a Bill considered urgent for the sake of national interest by the Cabinet of Ministers, can be referred directly to the Supreme Court by the president, seeking a ruling on its constitutionality. The reforms require the Supreme Court to provide a ruling within 24 hours to three days. The Bill can then be tabled in Parliament, debated and passed on the same day.

This means that the two-week period in which a Bill is published in the Gazette and tabled in Parliament will be reduced to one week.

What Happens Next?

The draft to the 20A was approved by the cabinet of ministers and was promptly gazetted on September 2.

While the draft is pending debate in Parliament prior to formally being legislated, dissent against the drafted reforms have already surfaced, and not just from opposition parties.

Reports have suggested that despite cabinet approval, several government members have voiced their opposition against the proposed reforms. Many of the challenges have focused on the abolishing of the National Audit Commission and the inclusion of dual citizens as parliamentarians.

Due to this, the government is said to be considering the incorporation of further changes to the draft during the committee stage of the parliamentary debate.

Similarly, others have also voiced their objections.

Opposition leader Sajith Premadasa of the Samagi Jana Balawegaya has said that the proposed amendment to the constitution is a first step towards a dictatorship.

Meanwhile, member of the National People’s Power alliance, attorney-at-law Harshana Nanayakkara, has said that if the reforms are enacted, it will revert the country to a “Stone Age”.

“The entire amendment is made in a way where the Parliament is converted to just a rubber stamp as the powers of the House is taken by the President,” he said.