Sri Lanka today celebrated 72 years of independence from the British with performances and parades at the Independence Square in Colombo. Although Independence Day celebrations have become a show of military strength, independence for Ceylon was a negotiated settlement that was the cumulative end to many events and movements throughout the period Sri Lanka was colonised by the Portuguese, Dutch and British.

Here are just a few of them:

Veera Puran Appu And The Matale Rebellion Of 1848

Photo Credit: Hiru TV/ Roar Media/ Jamie Alphonsus

A local hero, Veera Puran Appu was born Weera Hannadige Virabala Jayasuriya Patabendige Francisco (Puransikku) Fernando, in Moratuwa, in 1812. He lived a fairly trouble-free life until 1825, when he got into trouble with the local police and had to leave for Badulla, in the hill country, where he stayed with his second cousin Weera Hannadige Alexander Fernando, a wealthy arrack trader.

The hill country at the time was subject to foreign occupation and the forcible imposition of plantation capitalism. During this period of economic and social upheaval, compounded by heavy taxes and duties imposed by the British, many helpless and oppressed peasants including Puran Appu, turned to crime as an alternative.

In her 2015 book, Perennial Ferment: Popular Revolt in Sri Lanka in the 18th and 19th Centuries, historian Kumari Jayawardena finds many parallels between Puran Appu’s actions and ‘social banditry’, a concept formulated by historian Eric Hobsbawm in 1959. He makes a distinction between ordinary criminals and social bandits, whom he defines ‘groups of men whose activities are considered criminal by the prevailing official power structure, but not by the peasantry … for whom they fight injustice and oppression, and maintain the ideals of emancipation and independence.’

Notorious amongst the British and venerated amongst the peasantry, Puran Appu and another social bandit, Gongalegoda Banda, soon began agitating for open revolt.

On 26 July 1848, Gongalegoda Banda was proclaimed king by the head monk of the Dambulla Vihara, and Veera Puran Appu was appointed his deputy. Bandits no longer, Puran Appu’s army attacked Fort MacDowall in Matale, ransacking government buildings and property. However, their victory was short-lived. On their march to Kandy, the army was intercepted by British troops and Puran Appu was captured and executed by firing squad on August 8, 1848—the rebellion dying with him.

Despite its failure, the 1848 Matale Rebellion is seen as a significant transition from the classic feudal form of anti-colonial revolt to a modern independence struggle. Previous revolts against the British, such as the Uva Rebellion of 1817, had been led by the Kandyan aristocracy, who sought to replace British rule with the traditional monarchy of feudal Sri Lanka. And although Gongalegoda Banda played the role of a figurehead king, he, like Puran Appu, was not Kandyan, and was of low-caste. They became leaders, not by birth, but by igniting the spirits of discontented peasants, in a Sri Lankan independence movement led by ordinary people, for the very first time.

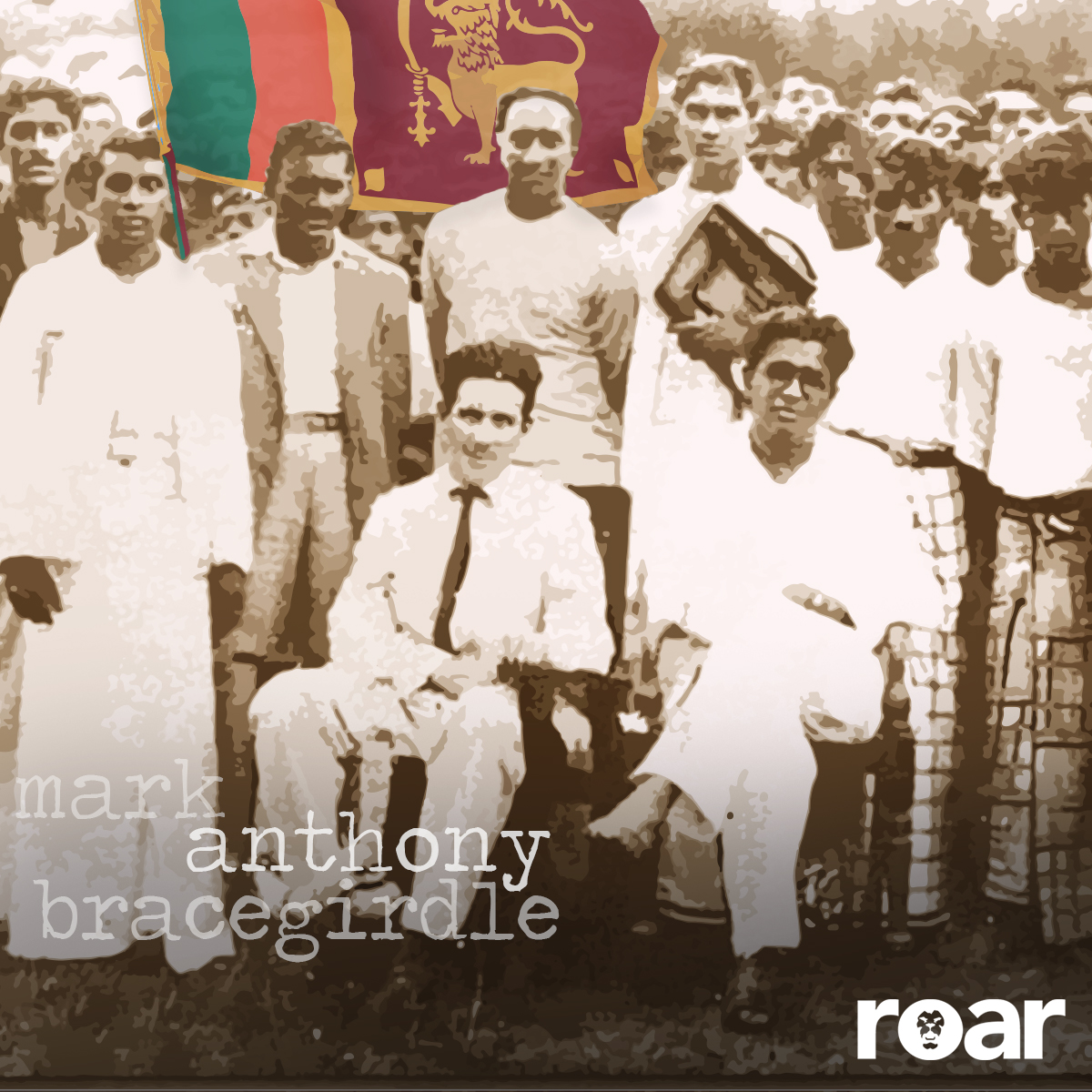

Mark Anthony Bracegirdle And The Labour Movement

One of the handful of European radicals in Sri Lanka’s independence movements, Mark Anthony Lyster Bracegirdle, an Anglo-Australian Marxist revolutionary, first arrived in Ceylon in 1936, to learn the trade of tea planting on the Relugas Estate in Madulkelle, near Matale.

Working closely with Tamil labourers on the estate, Bracegirdle was witness to the inhumane treatment they were subject to at the hands of their employers; he also noted that they received no healthcare or education, and lived in ‘line rooms, worse than the cattle sheds in England.’*

As dissatisfaction among the workers increased, he was dismissed for fraternising with them and taking their side in labour disputes. Bracegirdle then joined the local, Trotskyist Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP) party, which acted as a major political force in the independence movement, becoming later a member of the executive committee.

At a meeting at Nawalapitiya on April 3, 1937, Bracegirdle was called upon to speak to a crowd of over 2, 000 estate workers, who broke out into tumultuous applause and adulation. His appearance at this event was documented in a Marxist journal thus:

‘...The most noteworthy feature of this meeting … was the presence of Bracegirdle and his attack on the planters. He claimed unrivalled knowledge of the misdeeds of the planters and promised scandalous exposures. His delivery, facial appearance, his posture were all very threatening … Every sentence was punctuated with cries of ‘samy!, samy!’ from the labourers. Labourers were heard to remark that Mr Bracegirdle has correctly said that they should not allow planters to break labour laws and they must in future not take things lying down.’

The address angered the British, considering—especially—the fact that it was coming from a fellow white man, and Bracegirdle was ordered deported. Backed by the LSSP, Bracegirdle defied the order and went into hiding sparking an islandwide manhunt by the British.

Despite the fact that he was wanted, Bracegirdle made a dramatic appearance at a massive rally at Galle Face Green, presided over by Colvin R. de Silva, one of the founders of the LSSP, on 5 May, but the police were powerless to arrest him.

He was arrested, however, a couple of days later at the Hulftsdorp residence of Vernon Gunasekera, the Secretary of the LSSP. And although Bracegirdle was declared a free man at the conclusion of a case that was filed against him (the court decreeing he could not be deported for exercising his right to free speech), he returned to England soon after. The effect of his actions in Ceylon, however, reverberated long after he was gone.

Cocos Islands And The Failed Mutiny

The ‘Cocos Islands Mutiny’ is one of many unsuccessful attempts at gaining independence and occurred against the backdrop of World War II, when Ceylonese soldiers stationed at Cocos (Keeling) Islands in the Indian Ocean, approximately midway between Australia and Sri Lanka, orchestrated a rebellion against British troops.

The year was 1942, and the Ceylonese soldiers were on Cocos Islands to defend a vital cable and wireless station. According to Noel Crusz, the author of ‘The Cocos Islands Mutiny’, the Ceylonese troops were unhappy with the racism of their commanding officers.

The growing animosity led to a plan to take control of the island and hand it over to Japan, who were, by this time growing stronger. Following the bombing of the U.S. Pearl Harbour, the Japanese Empire had occupied Malaya, Burma, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, and the closer, Christmas Island and Crusz notes that sentiment in Ceylon was moving in favour of ‘fellow Asians’, many of whom hoped the Japanese would be their liberators.

On 8 May 1942, several members of the Ceylon Garrison Artillery (CGA) mutinied. The uprising had even been rehearsed a week earlier. But things did not follow through as expected. Most soldiers missed their aim. Ultimately, the rebels were overpowered and the uprising suppressed.

As a result of the failed attempt, officers of the CGA were shipped back to Ceylon and punished. Three leaders were executed at the Welikada Prison in August 1942. They were the only members of the British armed forces to be hanged for mutiny during the Second World War.

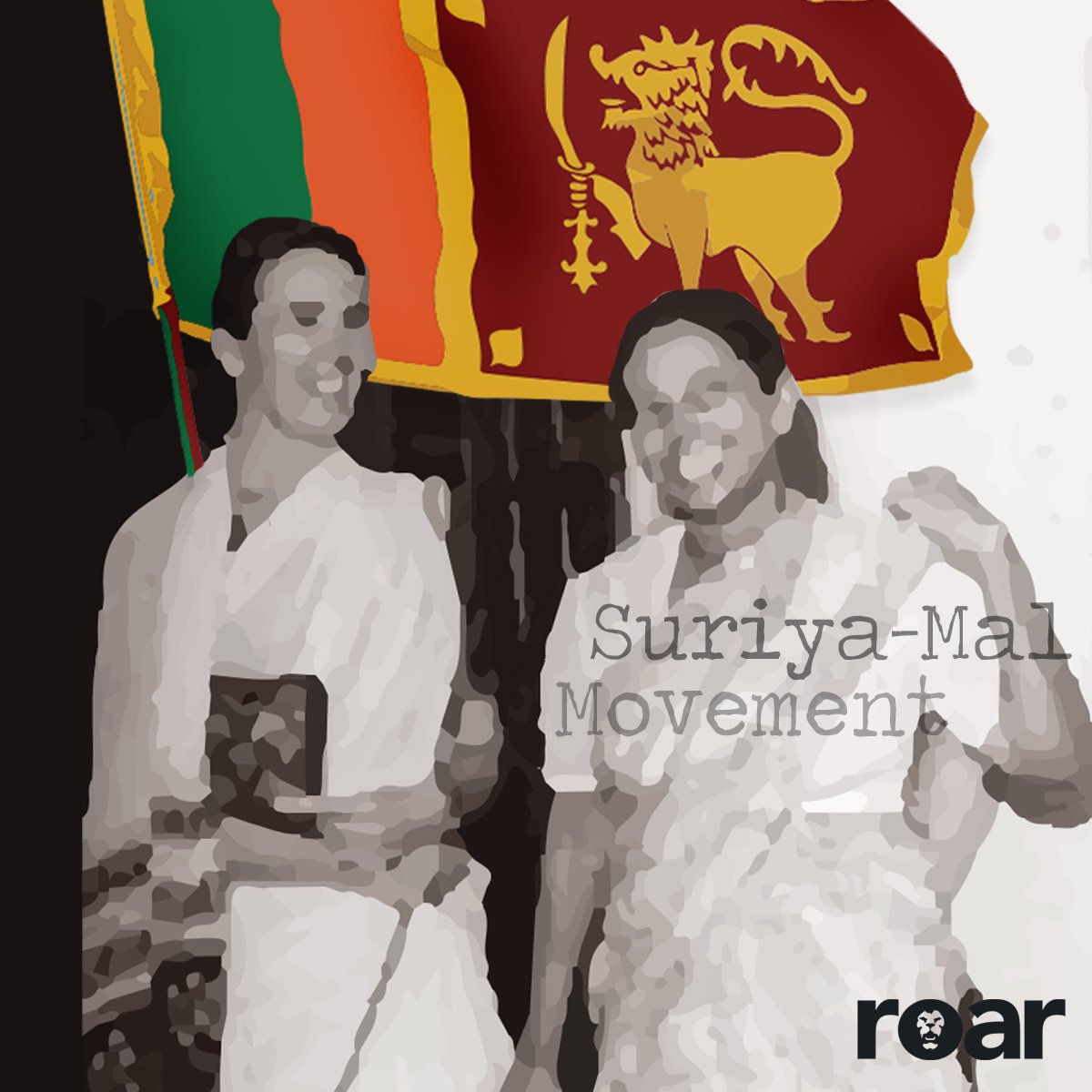

Remembrance Day And The Suriya-Mal Movement

The Suriya-Mal (portia tree flower) Movement was a grassroots movement that initially began in protest of the British sale of remembrance poppies to raise money for servicemen and women, but soon became a rallying point for the anti-imperialism and a growing call for independence.

Remembrance poppies had been sold on Armistice Day (11 November) in Ceylon since the end of World War I, but in 1931, a Ceylonese ex-serviceman, Aelian Perera, formed his own committee to sell a local sunflower, suriya and donate the proceeds to Ceylonese veterans.

Despite initial excitement, the movement fizzled out within a year.

But in 1933, a British teacher, Doreen Young (who was married to the founder of the Communist party, S. A. Wickremasinghe), wrote an article, The Battle of the Flowers for the Ceylon Daily News criticising the absurdity of Ceylonese donating to British veterans.

The South Colombo Youth League, one of many youth societies around the island, wanting and working towards independence, became involved, reviving the Suriya Mal movement, and electing Wickremasinghe as president.

The British authorities made an attempt to contain the movement by bringing in the ‘Street Collection Regulation Ordinance’, but the Suriya Mal movement gained popularity and lived on, with young Ceylonese men and women selling suriya flowers on the streets on Armistice Day in competition with the sellers of the poppy.

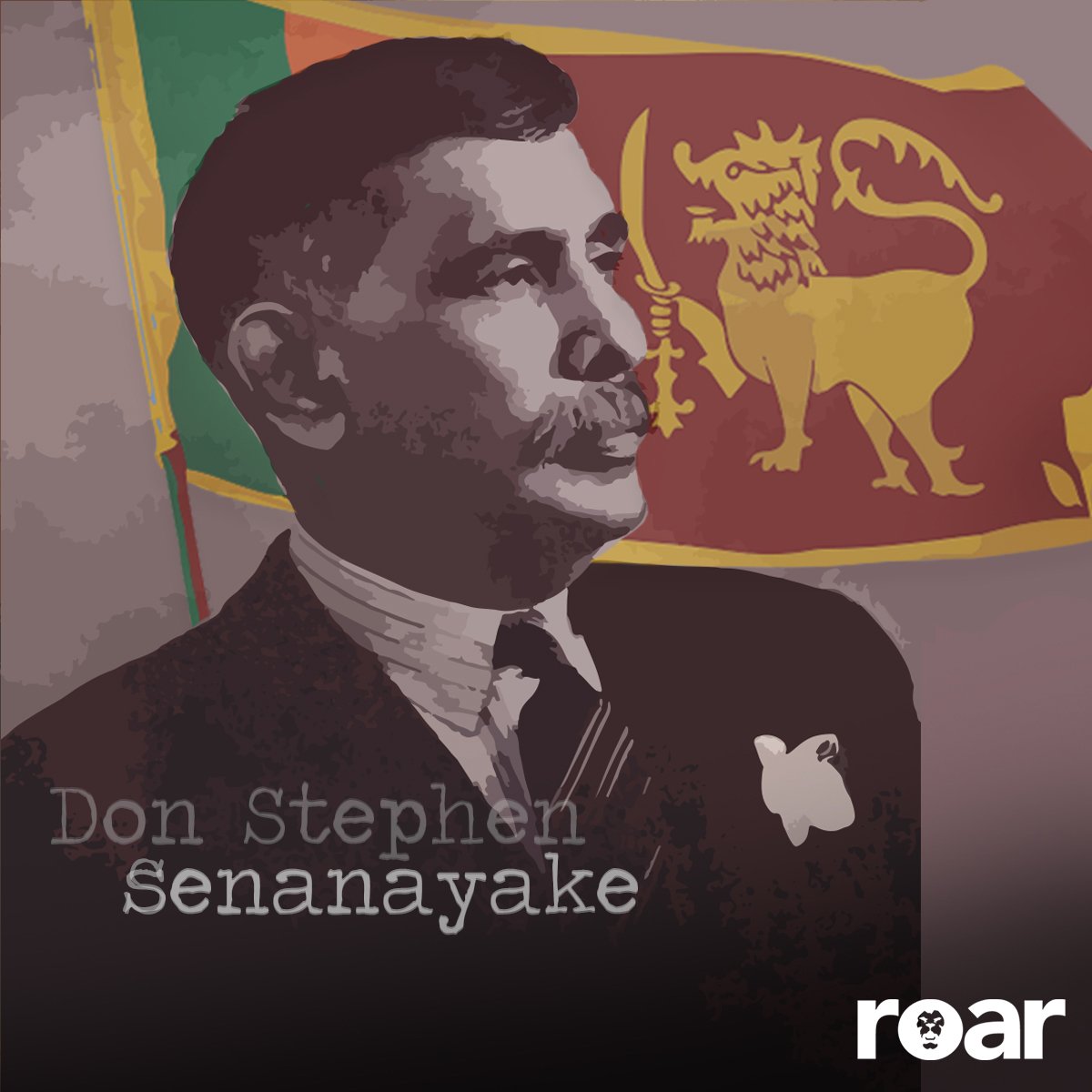

D. S. Senanayake, The Father Of The Nation

Widely acknowledged today as the ‘Father of Independence’ for successfully orchestrating the transition from colonial to self-rule and being elected independent Ceylon’s first Prime Minister, Don Stephen Senanayake was one of many Ceylonese that agitated throughout the years for a country independent of colonisers.

Born in the village of Botale, in the Hapitigama Korale (Mirigama, today) on 21 October 1883 to Mudaliyar Don Spater Senanayake—a businessman and philanthropist—and Dona Catherina Elizabeth Perera Gunasekera Senanayake, he was educated at S. Thomas’ College, Mutwal.

After he passed out, he joined the Surveyor General’s Department for a short time as a clerk before assisting with running his father’s extensive business holdings—an undertaking that included working as a planter and managing a graphite mine.

Senanayake and his brothers joined the anti-colonial temperance movement, which was perceived as a direct attack against the British, targeting as it did, the taverns that brought in a large revenue to the British Raj.

In 1924, Senanayake was elected to the Legislative Council of Ceylon. Seven years later, in 1931, he was elected to the newly formed State Council of Ceylon representing the Ceylon National Congress, a nationalist political party pushing for independence.

In 1943, he resigned from the National Congress disagreeing with its agitation for full independence, favouring instead dominion status similar to Canada and Australia. In 1946, he formed the United National Party (UNP).

Following India’s declaration of independence in 1947, Senanayake pushed for dominion status using the new constitution that was recommended by the Soulbury Commission that was tasked with drafting a new constitution for Ceylon.

The British government accepted Senanayake’s proposals for constitutional change and self-rule. In the subsequent Parliamentary elections, Senanayake’s UNP formed a government in coalition with the All Ceylon Tamil Congress.

On September 24, 1947, Senanayake was invited by the Governor-General of Ceylon Sir Henry Moore to form the island’s first cabinet as its first Prime Minister. The ‘Independence Bill of Ceylon’ was passed in December 1947, and on 4 February 1948, Ceylon marked independence with a ceremonial opening of Parliament.