During the years of European colonisation, Ceylon was often seen as the common voyager’s place of refuge or revelry. In a broader dimension, Alan Walters in Palms and Pearls or Scenes in Ceylon (1892) notes:

“There is no other country in the world which has, at different periods and by different races, been known under so many names as Ceylon nor is there any other round which a denser cloud of curious conjecture has gathered.”

It seems like a vanished notion. Or is it? It would be interesting to see if the old Ceylon could survive in Sri Lanka, via the cultural legacy of the 19th and 20th centuries. In Part 1 of our series, we summon a rich repertoire of people who can channel the unceasing charms of our cultural ethos and diversity.

Ayah

As British imperialism shaped the customs of the Indian subcontinent, the domestic servant class peaked in the 19th century. Bearing the same connotation as the Indian ayah, the word referred to domestic helpers who, back in the day, were imperative for most colonial settler families. The word ayah is said to have been derived from Anglo-Indian English. Further, it is argued that it actually stems from the Portuguese aia or nursemaid, coming from the Latin avia, meaning “grandmother.”

The Sawyer children and their ayah, Podihami, at their bungalow “Kudsia” in Colombo, Ceylon. Image courtesy: profiles.nlm.nih.gov

Ayahs mostly specialised in domestic tasks, foremost among which was the task of taking care of the employer’s children. They were often relegated to an inferior position to further enforce the imperialist mindset. Reflecting on the public opinion prevalent about Ayahs at the time, author N. Maisondeau wrote in his Summer in Ceylon (1909) that “some ladies require an ayah or lady’s maid, one of the most vexatious though useful creatures that one can add to an eastern household.” John Ferguson also made similar observations about ayahs in his book, Ceylon in the Jubilee Year (1996). “Sinhalese and Tamils,” he wrote, “made the most docile and industrious of domestic servants.”

Ayahs also travelled far from their own homes for employment, sometimes even crossing oceans. This is an advertisement¹ published in 1889:

AYAH- SINGHALESE AYAH. Cornelia, at Ayah’s Home 6, Jewry-street, is open to engagement, for Ceylon or India. Crossed 25 times. Excellent sailor.

September 23, 1889

Afghans

Commonly known as Pathans or as Kabul Bhais, the Ceylonese Afghans claim Pashtun ancestry. Like Arabs, they first arrived in Batticaloa by boats to trade with locals. At the time, with the rising conflict between the Tamil fishing castes, the area did not seem suitable for them. By the 19th century, they had established themselves as the predominant money-lenders of the country. H.R. Cowell had this to say about the Afghans:

‘These people will always be unpopular as money-lenders, they suffer under the hostility which Jews experience in other countries where the local people are improvident.’²

They were scattered across various parts of the island—which included Slave Island in Colombo—intermixing with the Moors and Malays and adopting the local lifestyle and dress.

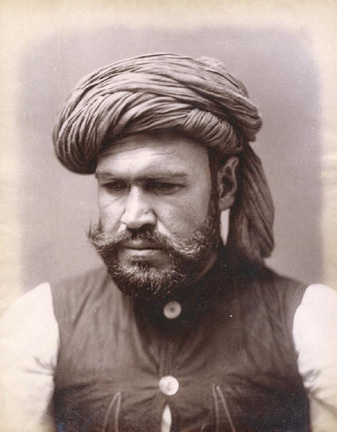

Portrait of an Afghan man. Image courtesy: asianworldnews.co.uk

Caroline Corne’s Ceylon, the Paradise of Adam: The Record of Seven Years Residence in the Island (1908), records a courtroom scene that involves an Afghan. Her depiction of the Afghan’s demeanour is significant:

“Conspicuous among them was the tall and imposing figure of an Afghan, defendant in the action now about to be heard. His khol-blacked eyes had in them a wistful, faraway look as of one half dazed, half above and beyond things terrestrial, the gaze of a seer or a dream.”

She also mentions their elaborate moustaches and their ‘silk cummerbunds’ that were used to carry daggers. The turban or—so writes Corne—the “conical centre” which “sat gracefully as well as jauntily on his flowing raven locks”, was the reason Afghans were often mistaken for Arabs.

American Missionaries

Rev. Samuel Newell was the first American missionary priest to arrive in Ceylon in 1818. Unlike India, where American missionaries were legally barred in 1793, Ceylon remained welcoming of missionaries because governors like Sir Robert Brownrigg were in favour of them. By 1812, an outpouring of Christian Americans had begun to reach Jaffna in ships.³

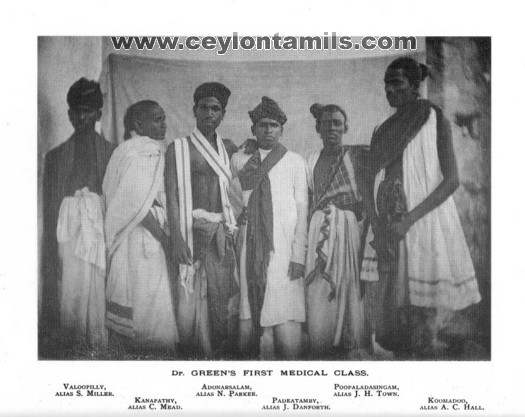

Dr.Green’s first batch of medical students who graduated in the 1850s (taken circa 1860). Image courtesy ceylontamils.com

The American Missionary Ceylon (AMC) was set up a year later in spite of the caste-related hindrances that were prevalent in Jaffna society at that time. Since the missionaries posed a threat to the local lifestyle, their main vocation became education and health. Physician Samuel Fisk Green was a member of this group. As an American expatriate in Ceylon, he is said to have not only founded the island’s first medical hospital in Manipay, now known as the Green Memorial Hospital, but also provided medical education for more than 60 native students who went on to qualify as doctors.

In Seven Years in Ceylon: Stories of Mission Life (1890), Mary and Margaret W. Leitch archive experiences of the work of missionaries in Jaffna. They assert that when the first missionaries arrived in Ceylon, they were unable to find a single literate native female.Out of a population of 300,000, only a few men and boys had been capable of reading. The missionaries opened day-schools for girls. Soon, nearly 500 girls were studying in mission schools, out of which 400 were enrolled in Mission Girls’ Boarding schools.

Miss Mary W. Leitch and Hindu girls in Uduvil, Jaffna, Ceylon. Image courtesy Pinterest

American missionary Eliza Agnew (1807–1883) was responsible for education at the Female Boarding School in Uduvil. With 42 years of teaching under her belt, her passion was to educate as many girls in Jaffna as possible. She was lovingly regarded as “the mother of a thousand daughters” by her pupils.

Coolie

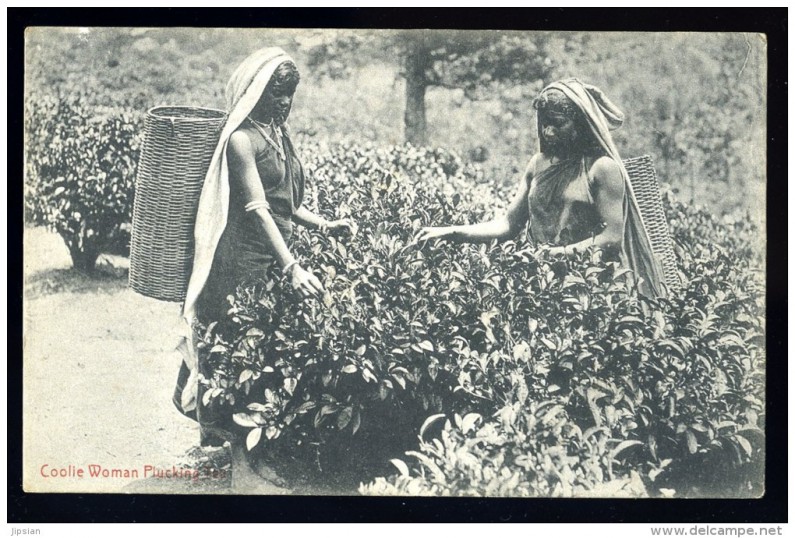

Perhaps borrowed from the Tamil word ‘kuli’ or ‘payment for work’, the word coolie was used to describe a class of indentured labour in the colonial times. By the 1820s, Tamils from South India, mainly Trichy, Madurai, and Tanjore, had begun to arrive in Ceylon as cheap labour for large-scale agricultural schemes. Kanganies, in charge of the labour force, were appointed by the colonial administrators as foremen, whom the coolies were indebted to. Although they were initially employed in coffee plantations, they were shifted to tea estates after the coffee industry failed.

Coolie women plucking tea. Image courtesy: images.delcampe.net

Arnold Wright’s Twentieth Century Impressions of Ceylon: Its History, People, Commerce, Industries, and Resource (1907) controversially states that there was “no indentured labour in Ceylon”. However, Kamalika Pieris indicates that illiterate coolies employed at the Ceylonese estates fell into exploitation. She goes on to mention that although Indians voluntarily enlisted to move abroad in the hope of better prospects, colonists frequently took advantage of them. Even upon their arrival, working conditions were so harsh that “they entered Ceylon at Mannar and had to walk about 150 miles to Matale.” Given how unfeasible this was, sadly, most of them did not make it to their destination. Those who did survive the journey were condemned to live their whole lives in an unjust labour system.

Elephant Hunter

Elephants have traditionally been a part of our cultural pageantry and history. In the meantime, while a trickle of imperial ascendants fell to Ceylon, elephant hunting was considered a ‘sport’, subsequently causing a bloodbath. Such a pursuit then, was well-received by the rural natives, who deemed it heroic. Today, this would be quite appalling to most.

A defeated elephant seen beneath Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in Ceylon. Image courtesy: imagesofceylon.com

Archduke Franz Ferdinand (1863-1914), whose assassination triggered World War 1, was notorious as an elephant-hunter. During his travels around the world between 1892-1893, he was deeply committed to trophy hunting. Nearly 100,000 trophies are said to have adorned his collection. An extract from his two-volume diary goes on to divulge his hunting triumphs, which included this passage on Ceylonese elephants:

Kalawewa, 11 January 1893

Soon Pirie returned in a highly excited mood and congratulated me vividly when I shouted out at considerable distance that I had bagged two elephants and told me that he had bagged also a strong elephant and wounded a second one. I had to show him my two specimen on the spot and personally cut off the two tails that serve as trophies in the whole of India and upon the particular request of the Sinhalese to mount upon my two elephants to mark the moment of possession.

Samuel White Baker (1821-1893), in whose honour the waterfall in Belihul Oya is named, widely toured the world in the name of exploration. Baker, a British “sportsman” is said to have thought that “Ceylon was a veritable sportsman’s Paradise.” He used his sporting skills to hunt elephants and deer. In his book, The Rifle and the Hound in Ceylon (1883), he writes: “And during the chase, an elephant drops from the herd at every puff of smoke. It is a curious sight, and one of the grandest in the world, to see a fine rogue elephant knocked over in full charge.” Major Thomas William Rogers was another prominent hunter. He is said to have been responsible for hunting over 1,600 elephants. Major Rogers was killed by a stroke of lightning in Haputale. It has been recorded in folklore that his curse followed him to his solitary tomb in Nuwara Eliya, which was also struck by lightning. To this day, a blemish can be seen on the surface of the tombstone, ostensibly where the lightning made contact.

By virtue, as we continue sewing together Ceylon’s record of the many ancestral faces left scattered through time, its rich ethnic diversity is also understood.

This article is Part 1 of a two-part series on the diverse inhabitants of 19th century Ceylon. Go here to read Part II.

Further sources:

¹Critical Perspectives on Colonialism: Writing the Empire from Below edited by Fiona Paisley, Kirsty Reid (2014)

²Sri Lanka in the Modern Age: A History of Contested Identities, Nira Wickramasinghe (2006)

³The Caste System of Jaffna and the Activities of the American Missionaries-A Historical View, Dr. K. Arunthavarajah (2015)

Featured image courtesy suriyakantha.org