South African comedian and current host of The Daily Show, Trevor Noah, has this particular joke in his standup routine about when the British came to Africa.

Skip to 3:04 in the above video to see Trevor Noah joking about the British coloniser’s language education system.

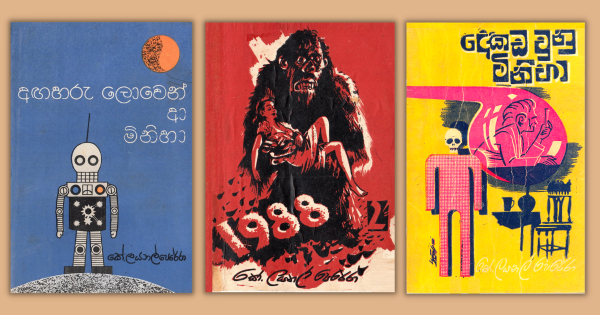

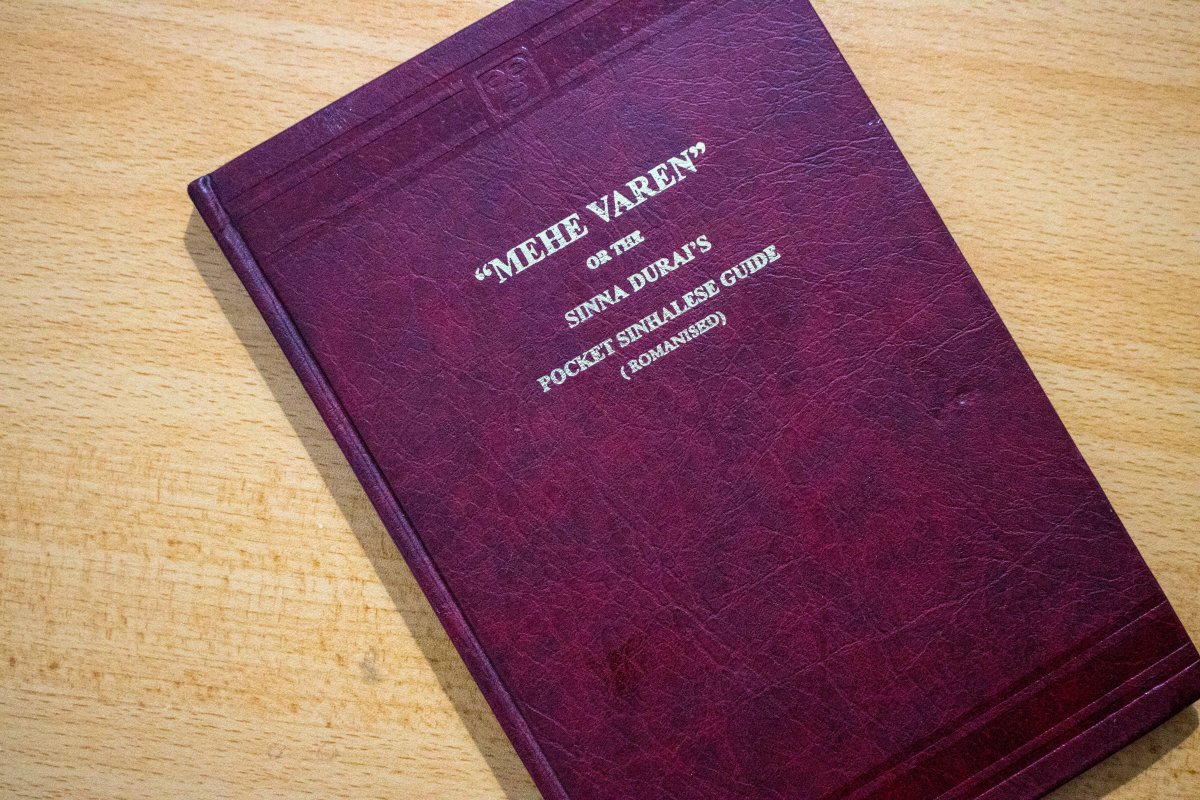

As our travelling friends would know, there’s nothing like a good phrase-book to learn the local tongues…which is perhaps what the British had in mind when this book was first published in Colombo in 1897:

“Mehe Varen”, or Sinna Durai’s Pocket Sinhalese Guide (Romanised) Being a Sinhalese Translation of A. M. Ferguson’s “Inge va!”

As stated in the prefatory note:

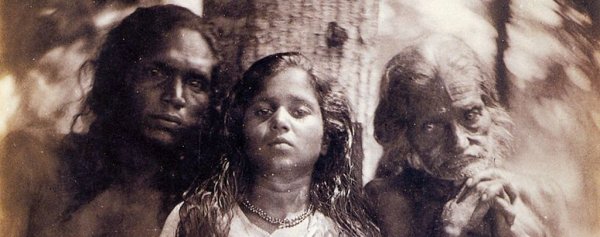

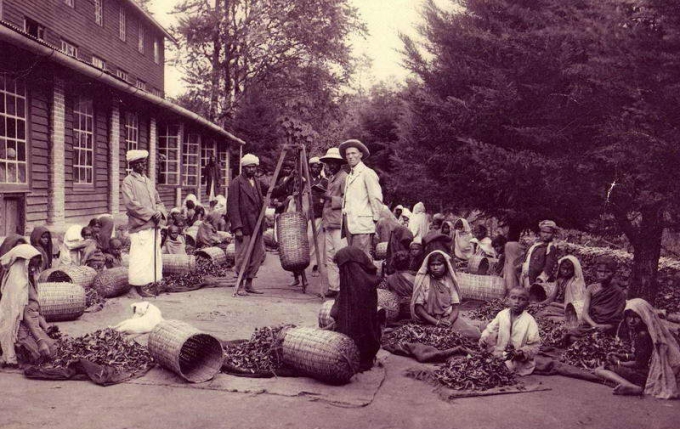

“This first edition of “Mehe Varen” has been prepared for our planting friends who employ Sinhalese labourers on their tea, cacao and Liberian coffee estates. These labourers are now very numerous, especially in the low country. The little book will also be use to all who employ Sinhalese servants.”

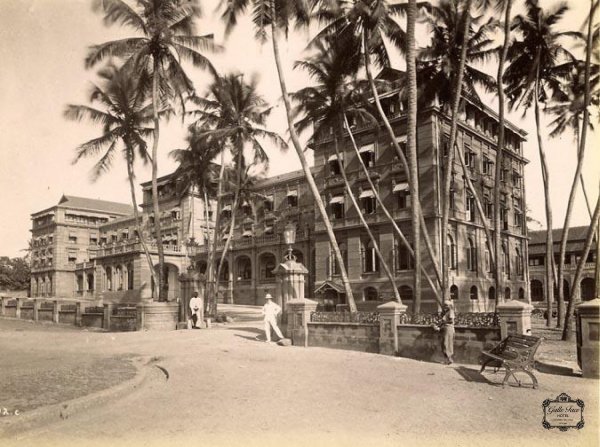

A British tea plantation

As any good phrase book Mehe Varen (which means “come here!”) gives excellent notes on how to pronounce the local language properly.

“1.In pronouncing Sinhala words, an accent should generally be put on the first syllable: long vowels are not necessarily to be accented. Thus karunāwa (‘favour,’ ‘mercy’) should be pronounced ‘kar’oonāva,’ not ‘karoonāva’; and vathukāraya (gardener) should be pronounced ‘vath’ookāray’ā’ not vathookārayā.

2. Each vowel should be distinctly and separately pronounced with the consonant or consonants to which it belongs thus—vathu-kā-ra-yā ; ka-ru-nā-wa.”

The plantation owners had to learn phrases that cover a variety of situations.

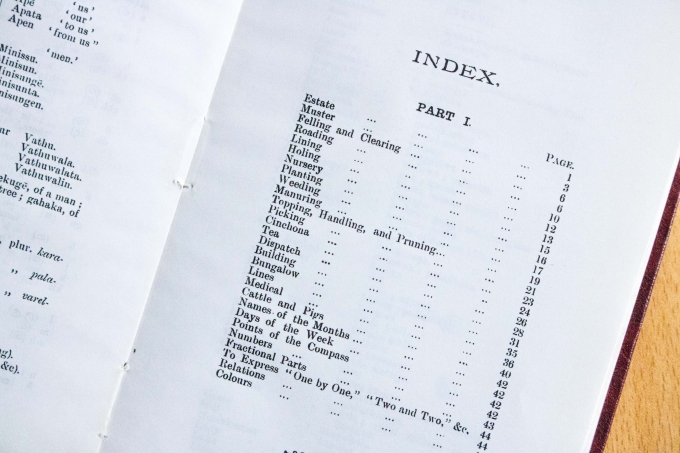

A good phrasebook anticipates where you will need to use it; on the street, at a restaurant, asking for directions, and so on. But as you can see, the aspiring plantation owner of the Ceylon of the 1800’s had different uses for a phrase book.

The index shows colourful sections such as ‘Estate’, ‘Muster’, ‘Topping, Handling and Pruning’, ‘Cattle & Pigs’ and so on, where you get such useful phrases such as:

“The name of the estate is upside down — Waththē nama væradhi athata dhamāla thiyenawā.

You lazy fellow, I have called you back three times to pick missed cherry — Ēi kammæliya ath arapu gedi kadanta thun særayak andagæhuwa.

Stick it in firmly — Haiyen hitinta ænapan”.

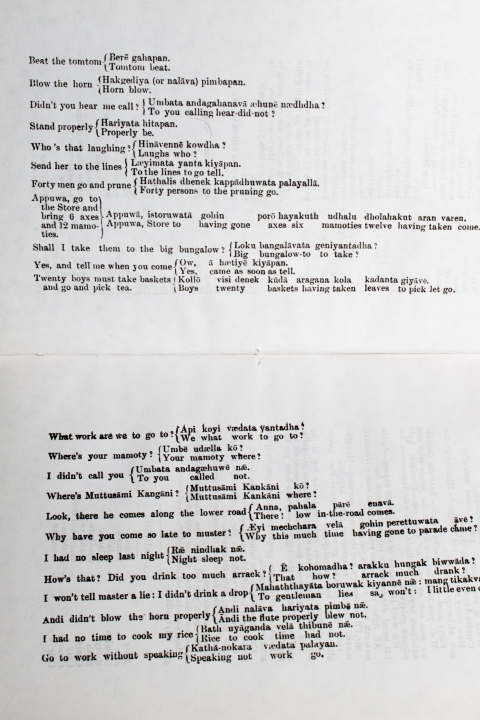

And many of these phrases are given in the form of dialogue in conversation, so the reader knows exactly how to use them.

“Why is that woman standing idle on the road? — Ē gæni pārē nikam innē æi?

Tell her to go to the lines at once — Dhæmma læyimata yanda kiyapan

Sir, it’s three o’clock — Mahattaya, dhæn thunai.

I don’t care if it’s three o’clock or ten o’clock, she’ll get no name — Thuna hari hathara hari mata kamak næ, eyāgē (or ægē) nama vætenne næ”.

While the book is about learning the local tongue, like in Trevor Noah’s stand-up routine, there are some phrases that they could teach the locals. For example:

The equivalent for “Beat the tomtom” is given as “Berē gahapan” or “Tomtom beat”.

The equivalent for “Didn’t you hear me call?” is given as “Umbata andagahanavā æhunē nædhdhā?” or “To you calling hear-did-not?”

How we use language towards other people is a good indicator of how they are treated. As such, Mehe Varen is a fascinating window into a how locals were treated at the hands of the British, who according to some, are to be lauded for bringing modernity to the island. We will never know now how Sri Lanka would have been if the British had not come. But we can see they weren’t on their best gentlemanly behaviour when they did.

Mehe Varen and other colonial era books have been reprinted by Asian Educational Services of New Delhi and copies can be found at some major Sri Lankan bookshops.