The 1950s are considered the ‘golden age’ of Sri Lankan journalism, producing many giants such as Denzil Peiris, Mervyn de Silva, Tarzie Vittachi, Ira Amarasekera, and Piyasena Nissanka. At the time, there were only two main news publishers in the country—the Times group and the Associated Newspapers of Ceylon Limited, better known as the ‘Lake House’.

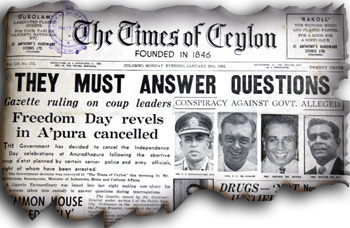

Both these companies were privately owned and had large audiences because newspapers and radios were the only methods of communications during that era. The Times group published two main newspapers—the Times of Ceylon and the Lankadeepa, while the Lake House published the Daily News, Dinamina, Thinakaran, and the Sunday Observer.

The journalists produced in Sri Lanka at that time were considered to be on par with their contemporaries abroad, despite working under conditions very different to our own: news publishers of the 1950s were not exposed to the advent of mobile phones, the internet, and smartphones, and news was gathered and produced in ways very different from now.

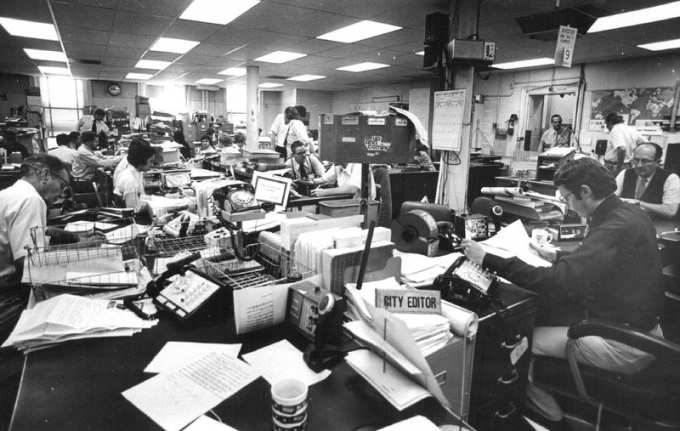

A busy newsroom at the Denver Post, with journalists working fiercely on their ‘beats’. Image courtesy newspaperalum.com

Dress code

Even the way a journalist dressed in the 1950s was very different to the way they dressed now, veteran editor Edmund Ranasinghe told Roar Media. Today, journalists mostly dress in casual clothing—an untucked shirt with pants or jeans, for instance—but the journalist of the 1950s was expected to wear a shirt and a tie. Coats were also mandatory if setting out for an assignment, as was a hat—a dictum probably influenced by the British.

One thing in particular that stood out then, from the way things are done now, is the manner in which relationships with ‘sources’ are cultivated, Edmund Ranasinghe told Roar Media. Back in the day, journalists actively cultivated relationships with politicians, ministers, departments heads, and other officers of import, and maintained close links with them to preserve their sources of news.

As there were no messaging or emailing platforms, it was important that the journalist kept in touch with decision makers and other people directly affecting his ‘beat’. It was common for journalists to make appointments with politicians, ministers, departments heads, and other people in the morning hours, during which meeting, information was gathered.

The ‘Times of Ceylon’, one of two main media publishers in the 1950s. Image courtesy thesundaytimes.lk

Deadlines for article submissions were at 1.pm, Dr. Edwin Ariyadasa, Sri Lanka’s oldest active journalist told Roar Media. Journalists who went out into the ‘field’ were expected to type out their articles and submit them to their respective News Editors before 1.pm.

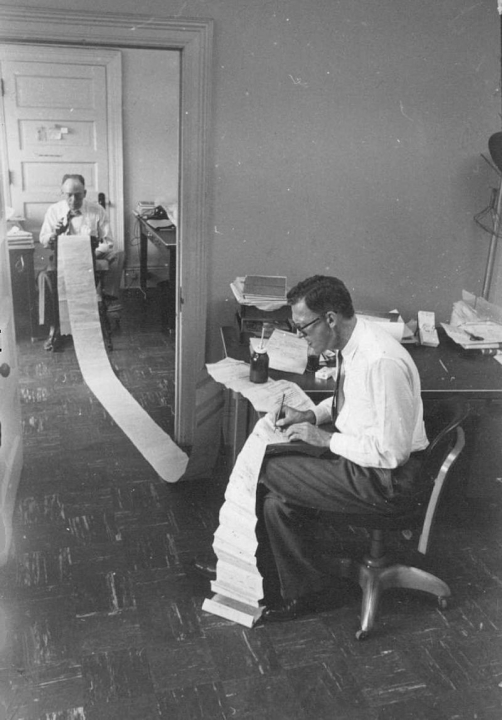

Whatever research was necessary for the article must also be accrued by these journalists through means far more difficult than the click away we are accustomed to; there was no internet, with its wealth of information, nor yet browsers like Google to make search easier. Instead, journalists had to pore through books and clippings at public and private libraries to find what they were looking for, and laboriously take down that information by pen before painstakingly crafting their ‘story’ for news publications.

The newspaper publishers (that is to say, the Times group and the ‘Lake House’) both had extensive libraries which were liberally used by the journalists in the 1950s and thereafter. Library staff maintained dossiers on notable figures of authority both in Sri Lanka and abroad, for easy access.

The ‘Daily News’, one of two English publications, published by the then privately-owned “Lake House”. Image courtesy sundaytimes.lk

The dossiers contained paper cutting with important information regarding people of national and international importance, and journalists were wont to sift through them to find a particular article in which a statement or action taken by a leader was documented.

It was also necessary for the newsman of yore to be well-read and possess a deep knowledge of current local and international affairs. While in modern times information is only a few clicks away, the journalist from the 1950s was expected to be on his/her toes, able to engage in deep conversation on matters of national and international importance at any given time.

D.F. Kariyakarawana, a former Editor at Lake House for the Janatha and Silumina papers, who worked at the Times Group and Lake House as a journalist in the 1950s wrote in his memoirs Memories of Seven Decades, “Editors back in the day thought a good English knowledge was essential even for a Sinhala language journalist going out on coverage. The same applied to photographers working with Sinhala newspapers. For instance, I remember three Burgher photographers who worked for Dinamina (a Sinhala daily newspaper) namely Don Pascal, Harvey Campbell, and Neil Moses. Even the cartoonist of the Dinamina newspaper in the 1950s was a Burgher by the name of Mark Gerrain. He could hardly write in Sinhala, although he was attached to a Sinhala paper.”

International news

International news was gathered by means of a teleprinter, which was connected to the Reuters newswire service, Edmund Ranasinghe told Roar Media. The machine would unceasingly print out news of international importance which was gathered by the International News Editor who earmarked the more important ones for the next day’s newspaper print. This was not an easy task and an International News Editor often had a team of journalists below him to help.

Two journalists attached to the Denver Post working through news that arrived via ‘teleprinter’

The newsrooms were male-dominated, Edmund Ranasinghe admits. He did say, however, that there were a few women who worked in newsrooms, mainly in the function of Sub-Editors or Features editors—a feature present even today. Because newsrooms jobs or jobs as reporters were not considered female-friendly, it deterred many women from taking up jobs in the newsrooms. However, two notable female journalists emerged from that era—Roshan Peiris and Ranji Handy.

The kickback on smoking indoors had not taken place yet, Dr. Edwin Ariyadasa said, guiltily admitting he had been a chain smoker when he was younger, to the extent he had a lit cigarette in his hand, even while having lunch.

“Till I developed a cough,” he said. “After which the doctor told me, ‘Young man, you will be dead before you turn 30 if you continue this way’, and I quit the habit from that point on.” That didn’t stop the other writers and editors from smoking both pipes and cigarettes, however, as smoking continued unabated in the newsrooms.

Often, by the time lunch was over, a sizable proportion of the newsroom was already ‘in the cups’. It appears that this did not affect their work because some of the finest journalists Sri Lanka produced were from that era.

Fraternity

Because the two main newspaper publishers were based in the Fort area, journalists from the rival papers often fraternized with each other at the cafes and restaurants on Chatham Street, Hospital Lane, at the Nippon Hotel, at the Lord Nelson, and the National Bar. It was customary for reporters to hang out at these restaurants and bars after work or during the day. It was here that many interesting stories were exchanged over a drink and ideas—part of a journalistic lifestyle.

D.F. Kariyakarawana writes in his memoirs, “During my days at the Times group, it was almost a daily ritual to go to Ratnagiri, after work (Ratnagiri is a hotel and bar located opposite to the WTC building at Echelons Square, Colombo Fort). Neville Dillamort, Chief Sub Editor of Times of Ceylon, and Ervin Moonamalai, the Chief Reporter of the paper, also joined us. Almost a half of my monthly salary was spent on Ratnagiri. Aside from drinks, our lunch was also bought from Ratnagiri.”

This tradition appears to be perpetuated even by modern journalists, who often visit the Ratnagiri and other smaller bars in the Fort area to fraternize with each other over stories. Although the way stories are gathered, crafted and published has changed so much with the advent of the internet and web publishing, there are many aspects of the newsroom that remain unchanged.

The passion a journalist has for pursuing a story, the idea that newspapers can create change, can chronicle events for posterity, continues to live strong in the mind of aspirants. Journalism is not easy, nor yet a popular career for many, but for those who choose it, it is a literary life.

Cover: The landmark ‘Lake House’ building, that still stands today. Image courtesy lakehouse.lk