Nestled in the Palani Hills of western Tamil Nadu, the hill station of Kodaikanal owes its foundation to Christian missionaries, who, in 1845, built a retreat there from the fierce dry seasons of the plain below.

Sangam literature identified the mountains with the landscape it called Kurinji, after the eponymous flower (Strobilanthes kunthiana, Sinhala neelakurinji). The shrubs bearing this flower occur in the montane shola forests, blooming once every twelve years and colouring the hills blue.

The deity Seyon (“the Red One”), identified with Murugan or Skanda, the God of Kataragama, presided over the Kurinji landscape. It therefore seems apt that the flower’s name, and the eponymous landscape, should be borne by the Arulmigu Kurinji Andavar Kovil, the “Temple of the Lord of Kurinji of abundant grace”, sacred to Murugan.

Former Times of Ceylon editor and The Hindu columnist, the late S Muttiah wrote in Honouring the Kurinji, in The Hindu, 3 May 2015:

And when I came to the Kurinji Andavar temple, a long forgotten connection suddenly dawned on me. The temple was built as the Sri Kurinji Easware temple in 1936 by Lady Ramanathan. Now, Lady Ramanathan was an Englishwoman who was born in Australia where her father was into gold mining. All references to her maiden name record her only as R.L. Harrison.

Music And Theosophy

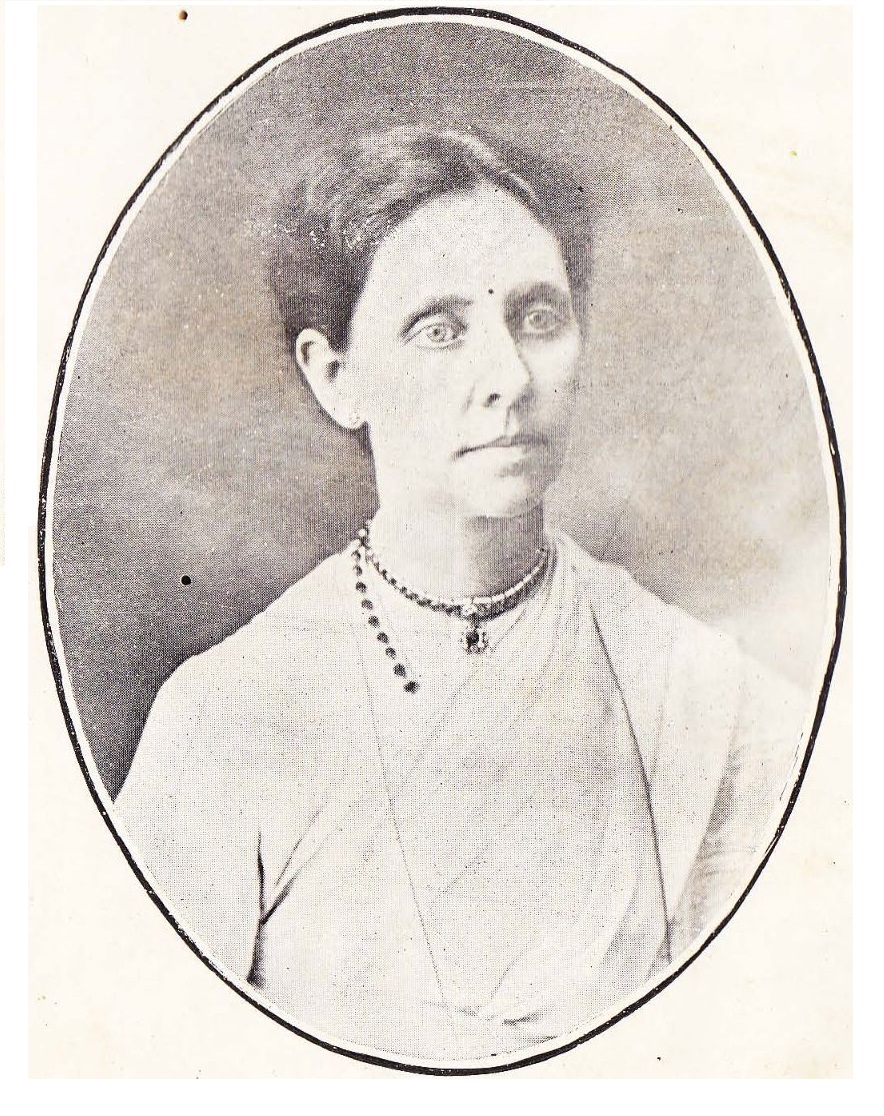

Lady Ramanathan was born Rosa Lilian Harrison, in Victoria, Australia. Her parents, Frederick Drake Harrison and Mary Lloyd Poole, had both emigrated from England to Australia as children. Lilian attended Eliza Kelsey’s Dryburgh House School in Adelaide and Queens College, an Anglican school for girls, in Ballarat, Victoria, where she won prizes for painting, music, recitation and fancy work. In 1889 she received a scholarship from the Commercial Travellers’ Association to attend Adelaide University, enrolling in the Bachelor of Music degree course.

As capitalism undermined old moral and spiritual certainties, the Russian countess, traveller and occultist Helena Petrovna Blavatsky and US Army Civil War veteran and lawyer Colonel Henry Steel Olcott founded the Theosophical Society in New York in 1875, aiming to resuscitate ancient wisdom, to counter both established religion and modern materialism, and to promote universal brotherhood. In 1891, Olcott delivered a lecture on Theosophy in Adelaide, and, together with seven “truth-seeking” professionals, formed the Adelaide Theosophical Society. “Rosa Lilian Harrison,” its current president Gaynor Fraser told this writer, “was a Foundation member of the Adelaide Theosophical Society.”

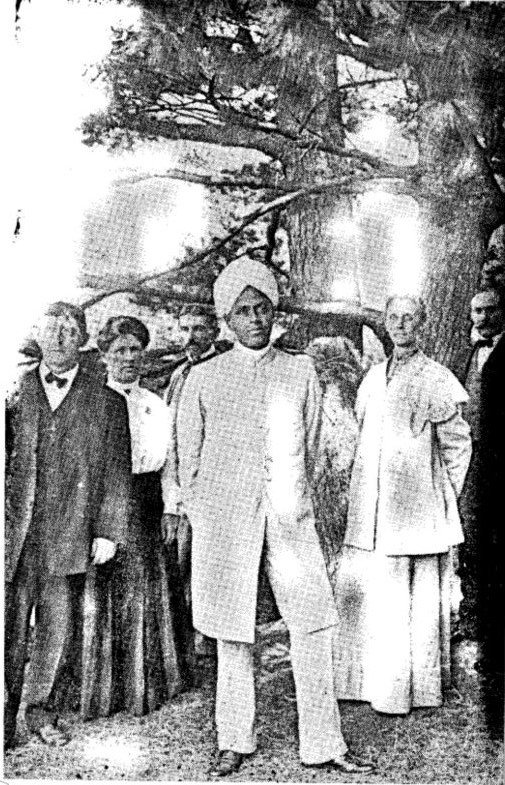

Ponnambalam Ramanathan

Theosophy drew Harrison to Sri Lanka, where she met and fell under the spell of Solicitor General Ponnambalam Ramanathan. Twenty-two years her senior, Ramanathan came from a wealthy clan of native civil servants originating in the Jaffna peninsula. Having attended Royal College, Colombo, and Presidency College, Chennai, he became an advocate of the Colombo Bar in 1874, in which year he married the heiress Nannithamby Sellachchi Ammal, settling at ‘Sukhastan’, a large house in Ward Place, Colombo.

Ramanathan edited the official law reports for a decade, was appointed to the Legislative Council in 1879, called to the bar at London’s Inner Temple in 1886, and invested with the honour of Companion of the Order of St. Michael and St. George (CMG) three years later. Appointed Solicitor General in 1892, he became, in 1903, the first Sri Lankan to take silk.

In his Life of Sir Ponnambalam Ramanathan, N. Vythilingam said that the secret of his rapid rise “lay in the fact that he was before everything else a philosopher and man of religion.” Arulparanandha Swamigal, a Hindu mystic from Tanjavur, in Tamil Nadu, had managed to “wean him from the sensuous materialism into which he was fast sinking and set him firmly on the path of piety and spiritual endeavour.” Arulparanandha introduced Ramanathan to the Saiva Siddhanta — a dualistic philosophy aimed at enlightenment through the Godhead of Siva — in which he became an authority.

Lilian Harrison, impressed by his erudition, became his disciple. “She knew she had found her Guru,” wrote Vythilingam, “and would not depart from him until she had achieved her life’s purpose… She renounced all ties of home and country and strove at his feet to solve the manifold questions of life and religion.”

Princeton religious history expert Richard Fox Young and former Jaffna Bishop Subramaniam Jebanesan wrote in their book The Bible Trembled that Harrison had originally come to Ramanathan in a state of religious uncertainty, although convinced that Christianity was empty of truth. She was, however, convinced by him not to dismiss the Bible so lightly, they wrote.

Ramanathan lectured her on the Bible, and she collected, edited and published in London her notes on his lectures as Gospel commentaries, attributing them to her “beloved teacher”, Sri Paránanda, as she identified him. The first,The Gospel of Jesus according to St. Matthew: as interpreted by R. L. Harrison by the light of the godly experience of Sri Paránanda, an annotated version of the Gospel published in 1898, made a considerable impact in spiritual and religious circles.

New Zealand journalist Hambers Danver wrote:

Miss Harrison’s desire for spiritual knowledge led her to the East, where the sun that lights the world by day and the spiritual sun that guides men who have eyes to see have always risen; and here in the East, the Voice that has spoken through her most earnest and truthful Teacher is now embodied in a handsome volume, every page of which is instinct with the Spirit of Truth.

She followed it up in 1902 with An Eastern Exposition of the Gospel of Jesus According to St. John: Being an Interpretation thereof by Sri Paránanda by the light of Jnána Yoga, a much more detailed exposition of Ramanathan’s philosophy.

America

These volumes greatly impressed New York lawyer and religious writer Myron Henry Phelps who, together with his “companionate wife”, the “Buddhist nun” Sister Sanghamitta (Countess Miranda Maria Canavarro), travelled to Colombo to meet Ramanathan in 1903, and studied with him for a year. Returning to the United States in 1904, Phelps became director of the Monsalvat School for the Comparative Study of Religion.

In June 1905, Ramanathan, accompanied by Harrison as his secretary, set off for London, and from there to New York and other parts of the US, on a tour where he delivered several discourses on “the unity of faith”. Their tour covered Eastern states of the USA, during which Ramanathan delivered lectures to Boston Zionists, to New York artists, and to students and faculty of Columbia, Cornell, Harvard, John Hopkins, and Yale universities. In April 1906, Harrison and he returned to London.

By this time, Harrison had changed her name from Rosa Lilian to Ráma Lílávati and, as R. Lílávati, she wrote a series of articles for the Indian Mirror, The Hindu, and the Ceylon Independent, describing Ramanathan’s peregrinations to and in the US. These she collected in a single volume, Western Pictures for Eastern Students, a mixture of a travel book, a description of western education and commerce, and a philosophical tract, apparently for the edification and instruction of South Asians.

In late 1907, Sellachchi Ammal having passed away, she and Ramanathan married in a civil ceremony in Wandsworth, South London. They had a daughter, Shivakamasunthari, who married Subbiah Natesan, the grandson of Arulparanandha, Ramanathan’s religious mentor. Natesan became his father-in-law’s secretary and Principal of Parameshwara College, Jaffna, being elected later to the State Council and to Parliament.

Legacy

Following her marriage, Lilavati appeared to shrink into Ramanathan’s shadow; apart from a period as Principal of the Ramanathan College for girls, which Ramanathan founded at Chunnakam, Jaffna in 1912. Vythilingam informs his readers with his accustomed verbosity that:

“To say that she, though heir to an alien culture and an alien upbringing, in every way exemplified the noblest traditions of Hindu womanhood by unquestioning obedience to her lord’s will, by perfect trust in and passionate adoration of him, by cheerful and complete subordination of her personal comforts to his is not to be guilty of an overstatement. His happiness, his comfort, his peace of mind was her supreme concern. She fulfilled his wishes with scrupulous attention to detail both when he was alive and after he was dead, never pausing to consider whether the wish accorded with hers. “My Master willed it,” she would say, “and therefore it must be done.”

By sublimating her own needs to Ramanathan’s, even after his death, she proved an exception to the norm; the other female mystics who had come to Sri Lanka, Madam Blavatsky, Annie Besant, Marie Musaeus Higgins, Elise Pickett, Sister Sanghamitta and Sister Padmavati (Catherine Shearer) proved to be strong-willed and steeped in theosophical ideas of gender equality. Even Florence Farr, Ramanathan College’s first principal, according to Kumari Jayawardena, in The White Woman’s Other Burden, chafed under the conservatism of an institution meant to produce ideal Hindu wives. Lilavati’s exaltation of Ramanathan extended to other males, to the detriment of her own gender: in Western Pictures for Eastern Students, she mentions women very rarely. Most unpardonably, I feel, she fails to even mention Sister Sangamitta, who first introduced Phelps to Ramanathan’s beliefs.

She also exhibited a degree of racism, strange in a Theosophist, even stranger in one who had married a non-White. She expresses this, as well as disdain for the British proletariat, in Western Pictures for Eastern Students:

There are· indeed thousands of “bushmen” in London, drawn from the body of the unemployable and unemployed. One need not go to Australia to look for them, ugly black creatures, a disgrace to humanity. Here in London their bodies are brawny. But their souls in both cases are as black as ever.

After Ramanathan’s demise in 1930, Lilavati donned the white robes of a Hindu widow, and would meditate in Kodaikanal where they had three houses, and later in the temple she built. In 1931 she published a short English version of The Ramayana, a copy of which she sent to Mahatma Gandhi. She supplemented its main text of 181 pages with 92 pages of notes. In 1942, the University of Ceylon conferred upon her the Honorary Degree of Doctor of Laws, in recognition of her services to education. She lived her final years with her daughter and son-in-law on the campus of Ramanathan College, and passed away aged about 80, on 31 January 1953. Her subordination to her husband meant that she left little by way of a legacy to future generations, a pity, in light of the considerable literary and artistic abilities she exhibited before her marriage, that she left such a small mark on history.