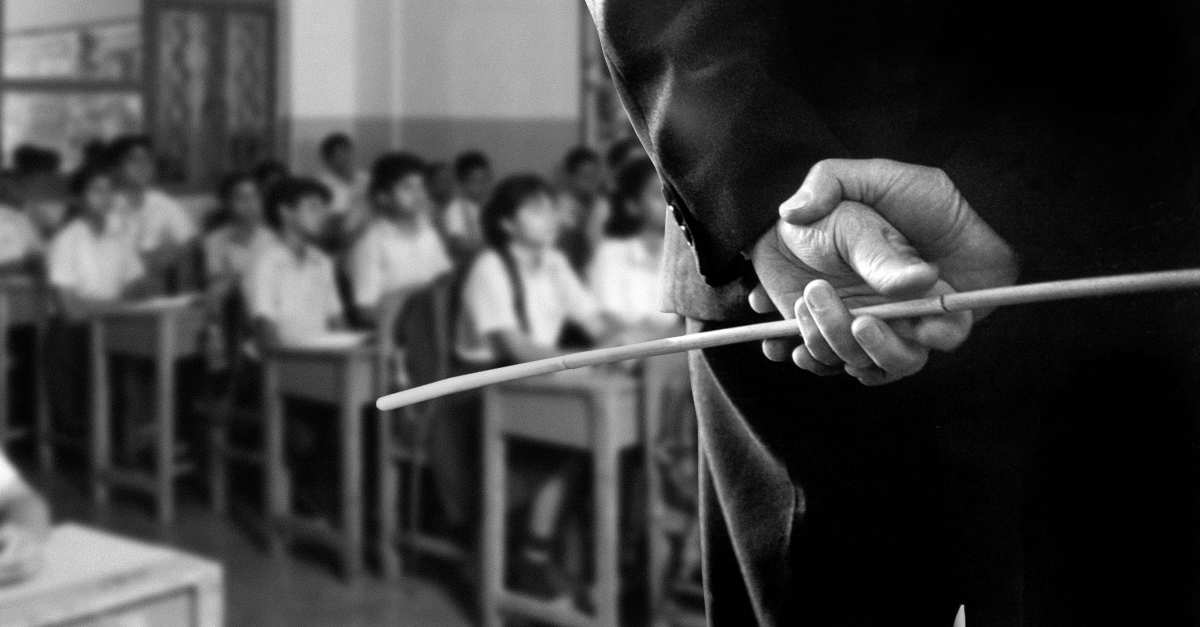

On July 9 this year, Principal W.R.H.M. Jayawardena of Polpithigama National School was sentenced by the Kurunegala High Court to three years’ imprisonment for caning a student in 2011. Two weeks later, a group of civil society organisations, including the Polpithigama Educational Zone Principals’ Association, organised a ceremony in support of Jayawardena, collecting 25,000 signatures on a petition for his release. The widespread support he enjoyed is proof that despite being illegal, corporal punishment in Sri Lankan schools is a practice that is accepted by many teachers and parents. But efforts are now being made to curb the practice.

On October 1 this year, a petition was submitted to President Sirisena by Stop Child Cruelty, a new organisation that has partnered with UNICEF, the Presidential Secretariat and the Sri Lanka Foundation Institute, calling for greater enforcement of Circular No. 12 of 2016, issued by the Ministry of Education, which bans physical punishment in schools.

However, as the case of Principal Jayawardena shows, the issue requires more than just legislation to tackle. “There are certainly problems with the legal system that need to be addressed, but attitudes to the practice will have to change as well,” said Dr Harendra de Silva, Professor Emeritus in Paediatrics, and founder of the National Child Protection Authority (NCPA), the government body responsible for the welfare of minors. A medical doctor by profession, Dr de Silva is passionate about creating awareness about the issue in his individual capacity. “In the ‘80s, when I was working as a doctor in Galle, I started to notice that a lot of children came in with injuries caused by corporal punishment,” he recalled. “That was when I began contributing to the cause, and I wondered how many cases I had previously missed because I wasn’t looking.”

In 2017, Dr de Silva conducted a study involving schools in Colombo, Galle, Monaragala, Trincomalee, Mullaitivu, and Nuwara Eliya. The schools included those representing different ethnicities; sectors (urban, rural, estate); and types (government, private and special education schools). He found that 80% of the students interviewed had experienced some form of corporal punishment, while a whopping 53% had experienced physical abuse. “Corporal punishment and physical abuse exist on a spectrum, and the level of pain or injury determines where you are on the spectrum,” he said, “While you can say one is allowed and the other isn’t, it’s hard to draw the line — ultimately, all forms of harm are unacceptable.”

Harmful Effects Of Harsh Punishment

Harsh disciplinary actions are normalised in Sri Lankan schools, and not restricted to simply caning — other methods used to control unruly children include pinching, pulling ears, forced kneeling, and in extreme cases, choking, throwing objects at the student, and beating. Psychological abuse, such as harsh and insulting language to belittle, scare or humiliate children is also widespread — experienced by 73% of the students in Dr de Silva’s study.

“These forms of punishment are especially harmful during adolescence,” said child psychologist Tehani Gunawardene. “When children are embarrassed in front of peers, their self esteem and confidence is lowered, and other children bully those students that are targeted by their teachers.” A global study carried out by the Institute for Health and Social Policy at McGill University also found that fighting amongst students was lower in countries which prohibit corporal punishment.

Many people who have experienced corporal punishment in childhood later perceive those incidents as less traumatic than they seemed at the time, and believe that they haven’t had an adverse effect on them. However, the reality is that the lasting impact of violence can be hidden, and vary from individual to individual. Younger students who see violence being used to settle issues, may later come to think of it as the norm. This defective pattern of conflict resolution could lead to their own use of violence in later life.

“When a child is beaten, the trauma or impact may not be in the conscious mind,” Dr de Silva explained. “But it becomes embedded in the unconscious mind. What we mean by the unconscious mind is the limbic system, which is closely linked with emotion and instinct. Our conscious mind can control the unconscious mind, but in moments of stress or frustration, we are controlled by the limbic system.We see this when bilingual people swear in their mother tongue when they become angry. A father or a teacher who becomes angry may revert to what their unconscious mind has learned.”

Advocacy Against Corporal Punishment

According to Dr Tush Wickramanayake, founder of Stop Child Cruelty, there are many problems with both the legislation against corporal punishment and its enforcement in Sri Lanka. The foremost of these is the fact that the laws are ‘vague and contradictory’. “According to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, to which Sri Lanka is a signatory, corporal punishment is defined in Section 11 as ‘any punishment in which physical force is used and intended to cause some degree of pain or discomfort, however light’.

However, the 1995 Amendment 308(a) in Sri Lanka’s Penal Code defines only those actions which cause an ‘injury to health’ as a criminal offence. This definition excludes punishments like forced kneeling or pinching. Further, Article 82 of the Penal code states that “Nothing, which is done in good faith for the benefit of a person under twelve years of age, by or by consent, of the guardian of that person, is an offence.” Not only does this create an ambiguity in the law, but it also makes it very difficult to prosecute cases of physical abuse, as both parents and teachers often believe that corporal punishment is ultimately in the best interests of the child.

Dr Wickramanayake herself had to deal with this issue when her daughter was subjected to corporal punishment at an international school she was enrolled in. “She and nine of her classmates were forced to kneel outside the classroom for not bringing reading material that day,” she recalled. “When I tried to do something about it, I was blocked at every level: the school, the police, the child protection authority, and the courts.” Dr de Silva recalled an incident where a father lodged a complaint against two teachers who beat his son, but when he checked up on the progress of the case at the police station, there was no record of it in the books. “When a policeman receives a complaint, if he is not sensitive to the issue, and if he himself accepts corporal punishment as necessary and harmless, as many in Sri Lanka do, then he is simply going to discard it,” he said.

Changing Teaching Methods

The argument for better teaching techniques that focus on positive instead of punitive discipline is not a new one. For example, introducing a reward system for younger children using token stars—gold for good behaviour and black for bad behaviour—has been widely used at the primary levels. However, the goals of this system can also be misunderstood. Dr Wickramanayake recalled that the use of black stars for bad behaviour in her daughter’s school did not have the same impact as a reward.

Instead, she advocated for the adoption of a ‘rainbow system’, in which groups of children are encouraged to complete tasks in order to move up the rainbow, with a reward for each step. Each reward “could be as simple as taking their class outside,” she said. She noted that for teenagers, withdrawing privileges for misbehaviour worked better than rewards for good behaviour. Gunawardene explained that this technique, which reinforces good behaviour with rewards and removes privileges as a deterrent, is called ‘applied behaviour analysis’. However, she emphasised that “it must be consistent for it to be effective.”

Simply explaining to a child what he or she did wrong can also be very helpful, according to a study conducted by child psychologist Dr Piyanjali de Zoysa. Not only does verbal discipline help build a relationship with the child, but it also helps develop the child’s cognitive capabilities. By considering their own actions, children internalise the values the teacher wants to impart. In contrast, with physical or emotional punishment, the child may think that it is more important to avoid getting caught than to change their behaviour. Interestingly, Dr de Silva’s report found that positive disciplinary techniques are also being used in Sri Lankan schools alongside corporal punishment. However, teachers often attribute improvements in behaviour to direct physical punishment—which yields immediate yet short term results—overlooking disciplinary techniques that yield results gradually.

“The thing is, teachers have to deal with large classes, of up to 50 students,” said Gunawardene. “The difficulty in controlling a class of this size is compounded by a lack of space, and even a lack of fans in many government schools.” She also noted that the highly competitive school system places additional stress on teachers as well as students, adding that few have any specialised teaching qualifications, and even those that do are not taught class management techniques that use positive discipline. “While these difficulties may explain why teachers may resort to violence to manage and discipline students, it does not justify it,” Dr Wickramanayake said, “There is a culture which accepts and even encourages physical punishment.”

However, both Gunawardene and Wickramanayake agree that it is not constructive to blame and blacklist teachers who use corporal punishment, since this approach does not deal with the root cause. Dr de Silva noted that taking the legal route also has its limitations. “Teachers who don’t punish their students physically, for fear of the law, often turn to emotional abuse, which also affects children heavily,” he said.

Instead, he suggested other ways to change the culture that accepts and encourages severe punishments, such as conducting workshops for teachers. Dr de Zoysa found that seminars, whether large or small, helped to change the attitudes of parents. She explained that many parents were under the mistaken notion that corporal punishment was the way to ensure that their children are successful. By teaching parents other ways to encourage their children to be happy, there was more engagement with her programmes. While these measures do not offer instant redressal, activists hope that will slowly change the attitude of the Sri Lankan public towards this critical aspect of childhood education.

Global Information on Corporal Punishment: https://endcorporalpunishment.org/