Hot on the heels of the ‘no-confidence’, or ‘no-faith’ motion against Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe last month, the ‘Joint Opposition’ (JO), the largest opposition group in Parliament, is in talks to bring a no-confidence motion against Opposition leader and Tamil National Alliance (TNA) chief Rajavarothiam Sampanthan, on charges he sided with the government during the no-confidence motion brought against the Prime Minister. The JO is of the opinion that as the leader of the Opposition in the government, Sampanthan is duty bound to vote against the government. A final decision on if it would bring a no-confidence motion would be made after Parliament reconvenes on May 8, having been prorogued by the President on April 13. Meanwhile, Sampanthan made it clear in Trincomalee this week, he was prepared to face any no-confidence motion.

The JO has effectively wielded the no-confidence motion tool, having just weeks ago – on March 2 – brought a much publicized no-confidence motion against the Prime Minister, in which it laid a number of charges against the Premier, particularly that of economic mismanagement in the the three years since the coalition government took over administration, involvement in the Central Bank Treasury Bond scam and failing to curb anti-Muslim riots that broke out in Kandy last month, while functioning as Law and Order Minister. The ministry was later given to Ranjith Madduma Bandara.

That no-confidence motion was taken up for debate on April 4, and successfully defeated after a majority of the minority coalition parties—particularly the TNA and the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress (SLMC)—stood by the Prime Minister, isolating the JO and part of the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) that said it would support the motion against the Prime Minister. The Marxist Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) also supported the JO in its motion against the Prime Minister. Despite this apparent show of support, 122 Members of Parliament voted against the no-confidence motion, 76 voted in favour of, while 26 (mostly SLFP-ers who had initially pledged support) abstained from voting.

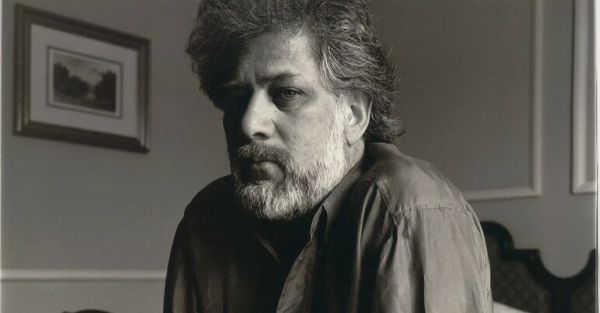

S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike faced a no-confidence motion in 1957. Image courtesy wikipedia

Crackers were lit late that night in Colombo and the suburbs as United National Party (UNP) supporters celebrated the triumph of its leader Ranil Wickremesinghe, over discontented members of the national unity government. As the unity government heads towards its fourth year in administration, it was made clear the interminable leader of the UNP enjoys a clear majority in the house. But this comes in the wake of President Maithripala Sirisena attempting to oust Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, when the results of the local government elections held on February 10 indicated the JO’s Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) had gained traction with the masses.

It was President Maithripala Sirisena’s attempt to oust the Prime Minister that acted as catalyst for the JO to bring a no-confidence motion against the Prime Minister, in the hopes of defeating him at a vote in Parliament and forcing his resignation. Such a scenario would have allowed the JO to partner with the SLFP, displacing the UNP in the national unity government. Since the JO—an ‘unofficial’ political party—is made up primarily of SLFP supporters (siding with former President Mahinda Rajapaksa in his disapproval of the alliance with the UNP), this would have made for an ideal situation for many of those against the policies and values of the liberal UNP.

The First Time?

This is not the first time the JO, which coalesced in the aftermath of the 2015 General Election, has brought a no-confidence motion against a member of the coalition government. But it is the first time it has considered bringing a no-confidence motion against a member of the opposition. This is not, however, unprecedented. In 1981, members of the UNP government brought a no-confidence motion against the (then) opposition leader and Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF) chief Appapillai Amirthalingam, which was passed in parliament. It was the first time a no-confidence motion had been brought against the leader of the opposition by the sitting government. The no-confidence motion against R. Sampanthan is equally farcical, and only indicates the JO’s desire to be considered leaders of the opposition in Parliament.

Earlier on, in 2016, and once again in 2017, the JO submitted no-confidence motions against Ravi Karunanayake. While Karunanayake defeated the first motion (145 against, 51 for, 28 absent), he publicly resigned over the second no-confidence motion that accused him of involvement in Central Bank bond scams of February 2015 and March 2016. His resignation was seen as a major victory for the JO.

There have been several other instances during which no-confidence motions have been brought against various members of parliament. This latest against the Prime Minister, is, in fact, the 47th instance of a no-confidence motion. There have been 23 no-confidence motions against governments, 13 against ministers, six against Speakers and Deputy Speakers, one against an opposition leader and another one against a chief justice (Shirani Bandaranayake). The no-confidence motion against Ranil Wickremesinghe is, however, the third no-confidence motion brought against a Prime Minister—the previous two being S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike in 1957 and Sirimavo Bandaranaike in 1975. Both were defeated, with S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike receiving 45 against and only 1 for, while Sirimavo received 100 votes against and 43 for.

Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike also faced a no-confidence motion in 1975. Image courtesy biography.com

But What Exactly Is A No-Confidence Motion?

A no-confidence motion is a statement by a number of members of parliament that demonstrate the elected parliament no longer has confidence in a member of the government—or a head-of state—to hold that position.

Cited as reasons for losing faith are if the elected government feels the person concerned is no longer fit to hold that position because they are inadequate in some respect, or they have failed to carry out obligations, or have made decisions that are detrimental to the functioning of the parliamentary body.

In the case of Ranil Wickremesinghe, the 14 reasons were submitted by the JO to demonstrate their lack of faith in his leadership, while in the case of the proposed no-confidence motion against Sampanthan, the allegation is that he acted in the interest of the government, rather than in the interest of the opposition, which role he is expected to play as the leader of the opposition in Parliament.

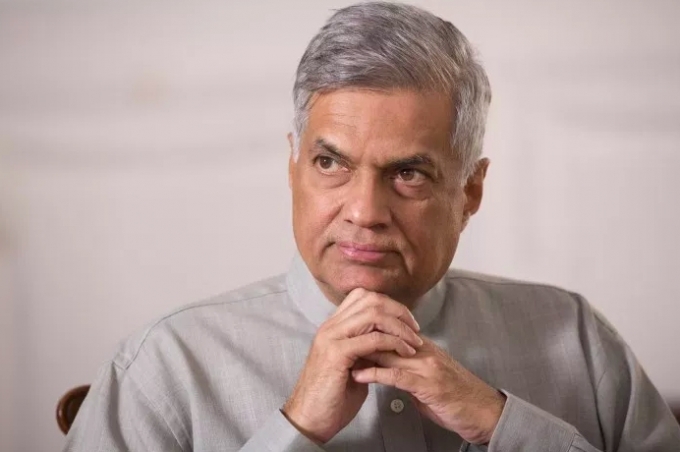

Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe successfully defeated the no-confidence brought against him. Image courtesy vasalaviththi.com

Fallout

Before April 2015, had the no-confidence motion brought by the JO been successful, it could have forced the Prime Minister to resign or be dismissed, allowing the JO a greater hand in the machinations of the government. With the passage of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution in April 2015, however, the Prime Minister’s position in office is constitutionally guaranteed. As per the 19th Amendment, 46 (2), the Prime Minister can continue to hold office unless he (a) resigns his office by a writing under his hand addressed to the President or (b) ceases to be a Member of Parliament. The 19th Amendment obliterates the clause (47) included in the 1978 Constitution that allows the President to remove the Prime Minister, effectively assuring the position of the Prime Minister in Parliament. Had the no-confidence motion against the Prime Minister been successful, rather than force him to resign or be removed, it would have been effective in discrediting him and the UNP-component of the coalition and done damage to an already fragile coalition government. Be that as it may, the no-confidence motion against Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe was successfully defeated by a majority of 46 votes, just as the previous no-confidence motions against Prime Ministers S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike and Sirimavo Bandaranaike were defeated in Parliament.

The no-confidence motion against R. Sampanthan too – if it is brought to fruition – is likely to have no impact on the status of the TNA as the opposition in government. Given that the TNA supported Premier Ranil Wickremesinghe during the no-confidence motion brought against him, it can be expected that members of the UNP in Parliament will vote against the no-confidence motion brought against TNA leader R. Sampanthan. The move – members of the ruling party voting for a member of the opposition – will be just as unprecedented as members of the opposition voting for the Prime Minister, as they did during the no-confidence motion against Ranil Wickremesinghe. The JO is likely they will face defeat should they choose to bring a no-confidence motion against Sampanthan, but, as Sampanthan himself pointed out, any party has the right to bring a no-confidence motion against any member of Parliament, and what remains to be seen is how this latest complication will play out.

Cover: The Joint Opposition is considering a no-confidence motion against Opposition Leader R. Sampanthan. Image courtesy srilankamirror