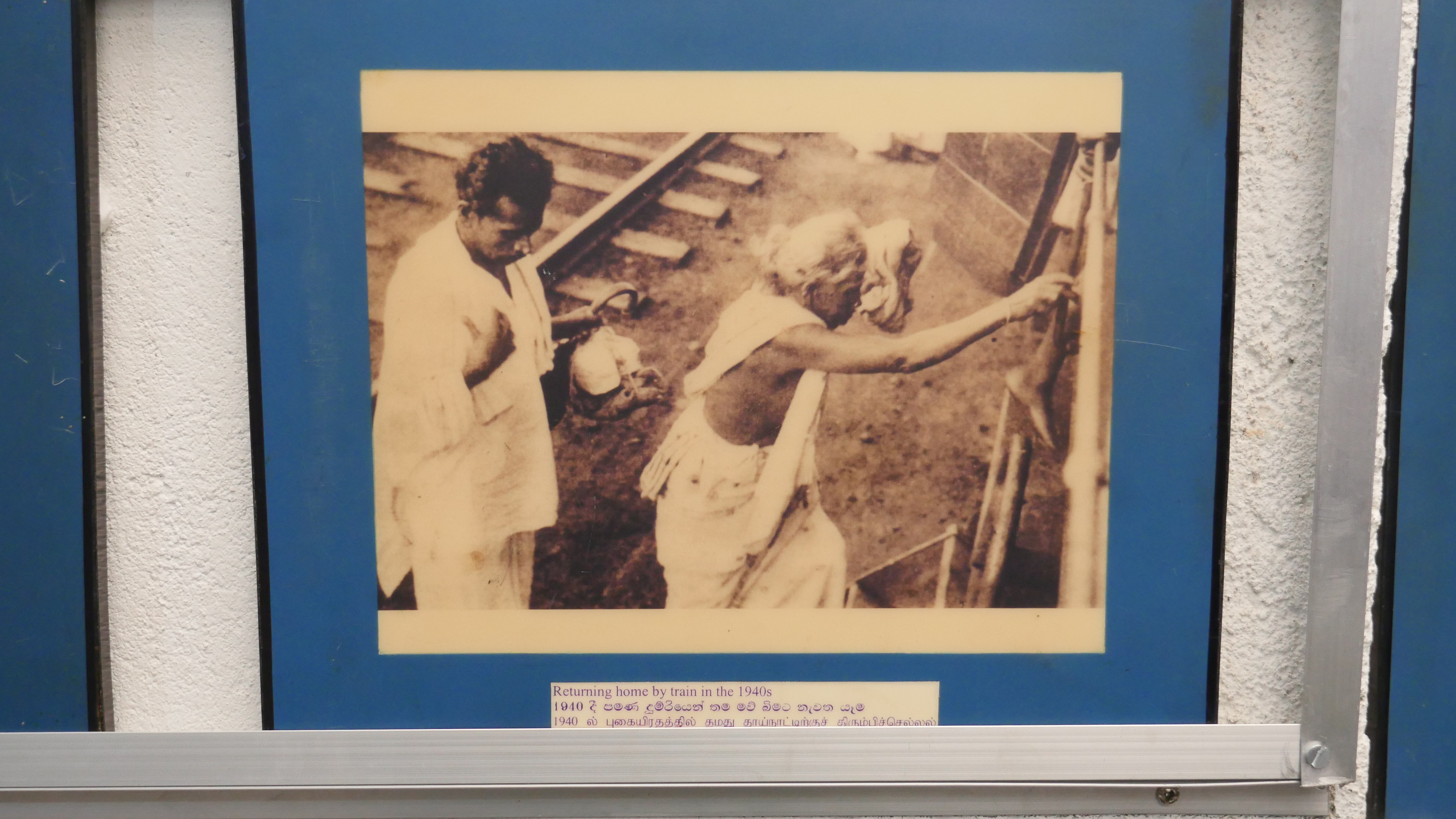

Nearly 200 ago, thousands of Indian Tamils embarked on an arduous journey from their homeland. Many were fleeing the oppressive caste system in search of a better life. They walked mile after weary mile from their villages to ports, where waiting boats and catamarans carried them across the Mannar Gulf to their new home in Ceylon. From Ceylon’s North, they journeyed once more – on foot, battling exhaustion, disease and death, to its hill country, where they began their new lives on coffee plantations. They stayed on there in squalid conditions as indentured labourers, little knowing that decades later, their children and grandchildren would still be toiling in the same hills, dealing with unchanged conditions.

Nestled deep in the verdant hills of the New Peacock Estate in Gampola, one institution is attempting to preserve and tell the stories of the plantation workers who have been largely forgotten in our national consciousness. The Tea Plantation Workers’ Museum and Archive was started in the year 2007 as an ISD (Institute of Social Development) project with the help of the University of Colombo’s Department of Archaeology. Conceptualised in 1997 by activist P. Muthulingam, who is also the museum’s director, its purpose is simply to safeguard the struggles, traditions and cultural heritage of the estate community. It took a decade for the initial idea to solidify into the simple but compelling trove of artefacts and information it is today.

“There is very little documentation available on this community,” says S Sathiyanaden, the programme officer in charge of the museum. “How did [the estate Tamils] come here? What are their struggles? What is their place in Sri Lanka’s history?”

What is special about the museum is the fact that it has been created within actual line rooms, the barrack-like structures which serve as the living spaces for estate workers. Here, within these cracked and windowless walls, families from the plantation community once lived and slept after hours of toiling in the hills. The museum consists of five such line rooms; each measures about ten by twelve feet. “These rooms are more than a hundred years old,” Sathiyanaden tells us. “You can see how small the living area is. Sometimes, there are three generations of [one] family living in the same small space.”

The first section of the museum is mostly preserved as it was from when estate workers lived there, a sort of snapshot from the past. By the dim light of the lantern hanging from the rafters, we see clothes strung up across the low ceiling; a makeshift bed of sorts, and a suspended blanket which once served as a cradle for a baby. Gandhi, Nehru and Subhash Chandra Bose look benevolently down at us from pictures that were brought all the way from India. “These were personalities that the estate community once considered heroes,” Sathiyanaden explains.

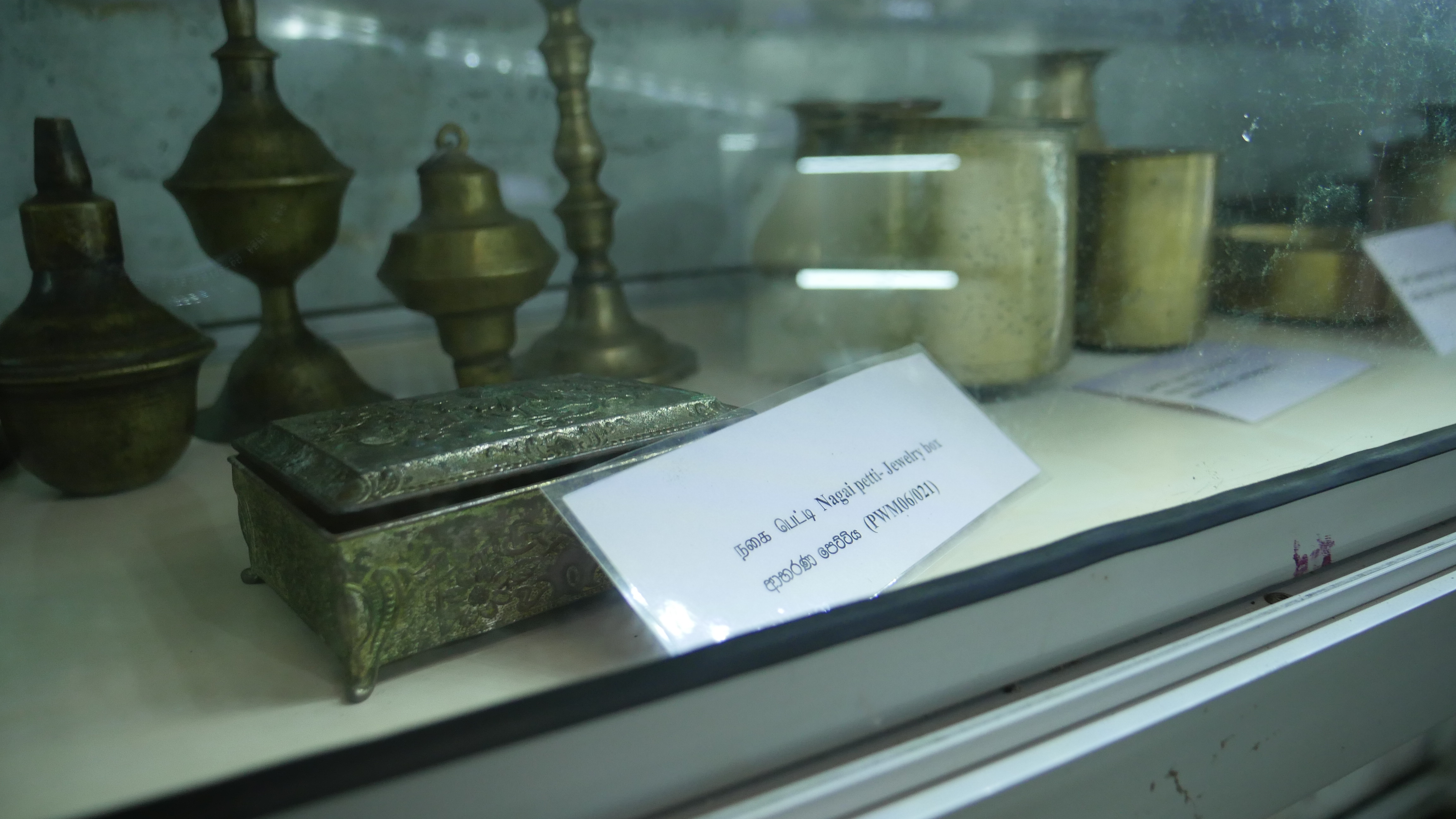

We also see various cooking utensils, household goods and tools. Some of them are easily identifiable, such as a grinding stone, a few copper water jugs, intricate brass lamps, milk pots and ladles. But there are also objects that carry particular cultural resonance for the community, such as a thukku peni (lunch basket), a sambar vaali (a copper curry bucket) and a poosai thattu (a tray used to carry flowers and grain during prayers).

Each exhibit carries the heft of nostalgia. One of the kudams (or water pots), for instance, belonged to a tea plucker called Meenatchi, and was given to her by her parents as dowry. The standing lamp (siru kutthu vilakku) came from a family in the Gomara estate, and was used to light up their places of worship.

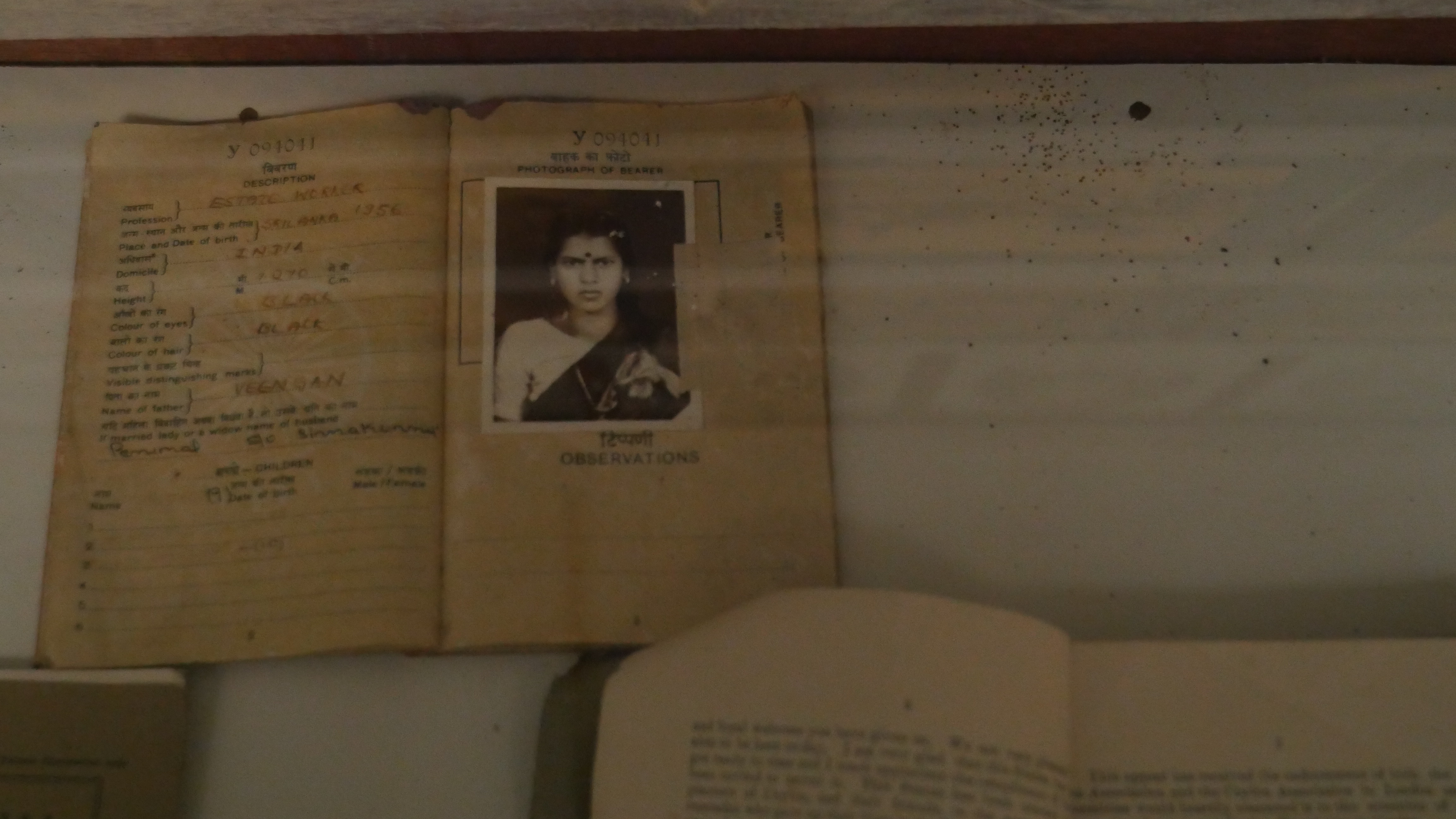

Another section of the museum contains cultural and ritualistic items like traditional musical instruments and symbolic ornaments, including a conch shell which was sounded during festivals and funerals, and a small udukku drum which was used by fortune tellers. Further inside is a gallery-like room that documents the history of Sri Lanka’s tea and coffee industry with photographs, records, several old books (including a copy of Ferguson’s Ceylon Directory, a comprehensive directory of the country, and its coffee and tea plantations, in the 19th and 20th Centuries), and even an old poem written by Ceylonese trade unionist C. V. Vellapullai called In Ceylon’s Tea Garden, which details the struggles of the estate worker.

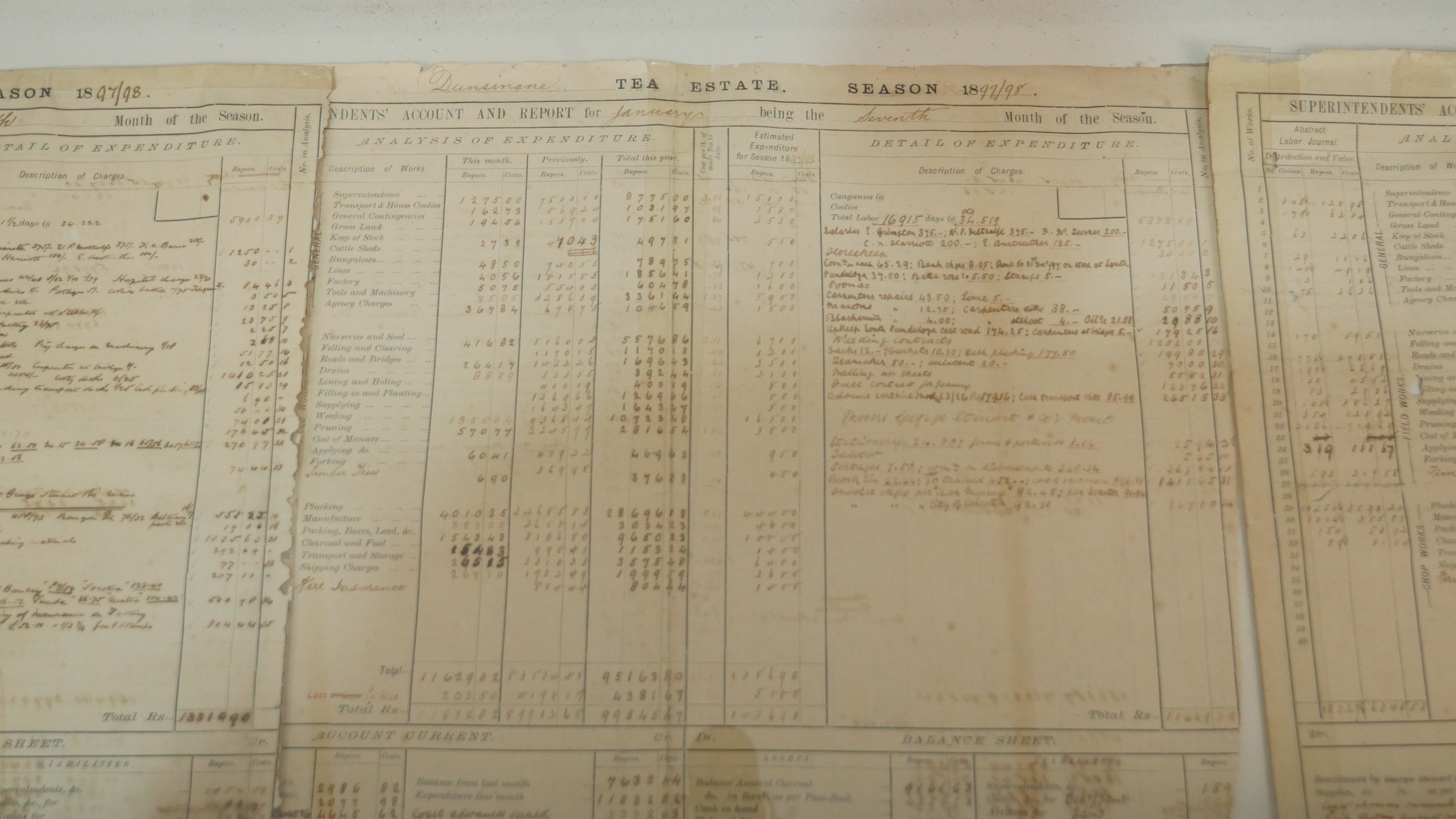

Sathiyanaden also shows us around the archives, which contain everything from ola leaf manuscripts dating back more than a hundred years to old ledgers that plantation managers maintained to keep records of finances, yield and other plantation-related matters.

As we leave, the words of the poet Vellapullai— simply printed on white paper and laminated, as a result of the museum’s sparse budget—remind us of the sombre and mostly forgotten struggles of the community.

My men!

They lie dust under dust

Beneath the tea,

No wild weed flowers

or memories token

Tributes raise,

Over the fathers’ biers!

O shame! What man

Ever gave them a grave!

Only God in his grace

covered them with His grass.