Following the advent of the ninth parliament led by President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, the introduction and enactment of yet another amendment to the constitution of the country is not far off.

The proposed amendment to the Constitution of Sri Lanka will mark the 20th instance it will be amended since its introduction.

With this on the horizon, it is vital to look back and educate ourselves on the constitutional history of the nation.

What Is The Constitution?

The constitution of a country is considered the supreme law of the state; the body of fundamental principles according to which a state and its citizens are acknowledged to be governed.

Sri Lanka has had two colonial constitutions and two republican constitutions.

The Two Colonial Constitutions:

The Donoughmore Constitution was the first constitution that was introduced during the British occupation.

Created by the Donoughmore Commission, the constitution served Ceylon from 1931 to 1947.

This constitution enabled general elections with adult universal suffrage: the first time a country under the care of the British Empire observed the one-person, one-vote principle and was given the power to control domestic affairs. Universal suffrage meant that women could vote — and therefore Ceylon became the first Asian country in which women voted at an election.

These reforms also saw the establishment and the transfer of (some) power to the Ceylon State Council, the predecessor of the Parliament of Sri Lanka, which came into being in later years.

Geoffrey Butler, one of the four members of the Donoughmore Commission, writing to D R Wijewardene (founder of the Associated Newspapers of Ceylon Ltd.) said, “After all, a Constitution is so much more than a mere document. It is a piece of history and demonstration of ideas. I felt that Ceylon was at a turning point in history. It is unquestionably the most politically advanced of the Colonies…”

However, the Constitution was not without its faults; the reforms required residence qualification to vote, which prevented migrant Tamil labourers from voting. Communal representation was replaced with territorial representation. Ultimately, this led to Tamil politicians boycotting the first election held under the new constitution, the 1931 Ceylonese State Council election.

The Soulbury Situation

In 1944, the second colonial constitution was introduced to the country, under the guidance of the Soulbury Commission, which was similar to its predecessor the Donoughmore Commission.

The reforms brought forward by the constitution ushered Dominion status ( a semi-independent Commonwealth realm) and eventually granted independence to Sri Lanka in 1948.

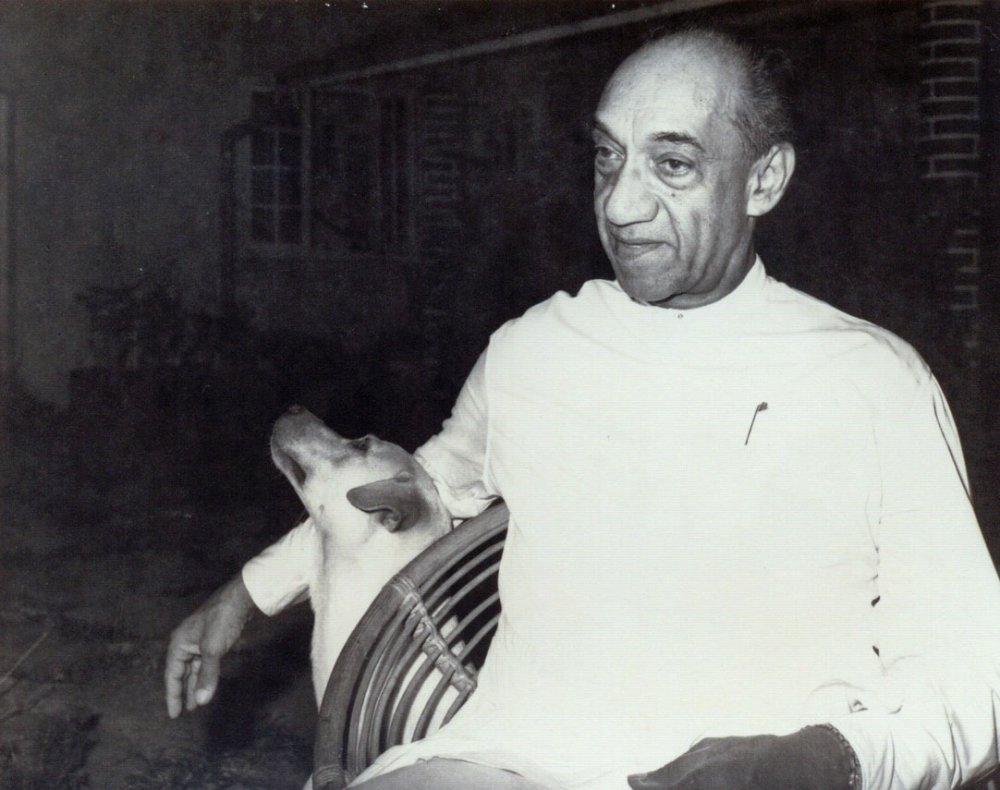

The constitution was drafted by D. S. Senanayake, who led the Board of Ministers under the advice of Sir Ivor Jennings, an eminent British scholar. The draft abandoned the Donoughmore Constitution and the formulation of a model akin to the Westminster system practised in the United Kingdom.

This meant that a House of Representatives was created, with power over domestic affairs, but exclusive authority over the defence and external affairs continued to be relegated to the British governor-general of Ceylon. A cabinet of ministers with a prime minister was responsible for the House of Representatives under the reforms brought forward by the constitution.

The main concern of minority representation following the Donoughmore Constitution was addressed through the Soulbury reforms when the electorates were delimited (setting out electoral boundaries to fix constituencies) in a new way to ensure that minority groups would secure more seats.

Even after gaining independence from Britain on 4 February 1948, the country remained a commonwealth of the British Empire. It was not until 16 May 1972 that the nation officially proclaimed itself as an independent republic.

The First Republican Constitution

The first republican constitution of the nation witnessed the country’s name being changed from ‘Ceylon’ to ‘Sri Lanka’.

Replacing the Soulbury Constitution with a new and improved one became a priority after the United Front alliance led by Sirimavo Bandaranaike won the 1970 general election with a two-thirds majority.

In their mandate prior to the election, they noted, “We seek your mandate to permit the members of Parliament you elect to function simultaneously as a Constituent Assembly to draft, adopt and operate a new Constitution. This Constitution will declare Ceylon to be a free, sovereign and independent Republic pledged to realise the objectives of socialist democracy; and it will also secure fundamental rights and freedoms to all citizens.”

However, Radhika Coomaraswamy in her essay titled ‘The 1972 Republican Constitution in the Postcolonial Constitutional Evolution of Sri Lanka’, highlighted: ‘The 1972 Constitution was in many ways a symbolic assertion of nationalism, twenty-five years after independence.’

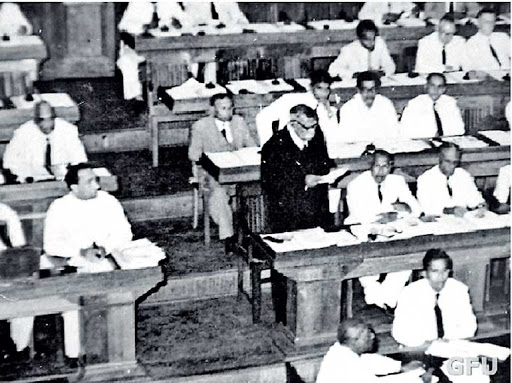

Accordingly, Bandaranaike convened a number of committees to draft a new constitution that was tabled in parliament, voted in and adopted on 22 May 1972 by a vote of 119 for and 16 against. The constitution was challenged by opposing parties—the United National Party (UNP) and other Tamil parties—who walked out of proceedings.

Under the reforms brought forward by the new constitution the following points can be identified as being key features:

- Sinhala was identified as the official language of the state

- Sri Lanka was declared a unitary state — the central government is supreme and may delegate powers to administrative units

- Buddhism was given a priority position

- Parliament term was restricted to six years

Enter J. R. Jayewardene

In the 1977 general election, the UNP won majority power in parliament. This was the largest victory a single political party managed to achieve in the country’s political history.

Making use of this momentum, the UNP’s J R Jayewardene sought to abolish the 1972 constitution with a new legislature. Accordingly, the new constitution that came into being on 7 September 1978 provided for a unicameral parliament and a powerful Executive President. Jayewardene became the country’s first executive president, after the new reforms were passed, and R. Premadasa was appointed the Prime Minister.

The new reforms introduced a form of multi-member proportional representation for elections to parliament, which was to consist of 196 members. However, the role of the parliament was somewhat reduced with the inclusion of the executive presidency; now the president could dissolve parliament a year after it was elected.

The reforms also introduced the use of referendums to approve critical changes to the constitution.

Since then, the constitution has gone through several amendments. Most provisions of the constitution can be amended by a two-thirds majority in parliament.

Following are the amendments:

First Amendment (20 November 1978): This amendment held that certain cases heard by the Court of Appeal could be transferred to the Supreme Court.

Second Amendment (26 February 1979): Amendments made to the procedure of resignations and expulsion of Members of Parliament.

Third Amendment (27 August 1982): To enable the president seek re-election four years from the first term. Accordingly, the president must declare his intention to appeal for a mandate for a further term, at any time after the expiration of his first term of office.

Fourth Amendment (23 December 1982): Extension of term of parliament. The amendment came into effect after a referendum held in December 1982.

Fifth Amendment (25 February 1983): To provide for a by-election when a vacancy in parliament is not fulfilled.

Sixth Amendment (8 August 1983): Prohibiting violation of territorial integrity: the amendment prohibited citizens from advocating for the establishment of a separate state within the country. The amendment was criticised at the time, as it followed the 1983 Black July riots.

Seventh Amendment (4 October 1983): Dealt with High Court Commissioners; the creation of Kilinochchi District which brought the number of administrative districts in the country to 25.

Eighth Amendment (6 March 1984): President’s powers increased to appoint President’s Counsels.

Ninth Amendment (24 August 24 1984): Amendment to adjust the salary scales of public officers who are not qualified to be elected as Members of Parliament.

Tenth Amendment (6 August 1986): To repeal the section requiring a two-thirds majority for Proclamation under the Public Security Ordinance.

Eleventh Amendment (6 May 1987): Reformed judicial powers of the High Court to address first time offences; to provide for Fiscals and Deputy Fiscals (prosecutors) for the whole island; also relating to sittings of the High Court, the number of minimum judges at a Court of Appeal case was amended.

Twelfth Amendment (25 September 1987): Even though it was proposed on 25 September 1987, it was not enacted due to technical errors.

Dr Asanga Welikala, an expert in constitutional law who is currently Director of the Edinburgh Centre for Constitutional Law, explained to Roar that the bill for the 12th Amendment was presented in Parliament by MP Dinesh Gunawardene, who was then a member of the Opposition.

“In terms of Standing Order 47(5) which then prevailed (now repealed), the procedure for a bill for the amendment of the constitution required a ‘Ministerial Report’ to Parliament. The then government did not provide such a report and the bill fell,” he said.

“However, due to a procedural anomaly, the unsuccessful bill was counted as an amendment for the purpose of numbering constitutional amendments. Therefore, even though there was in fact no Twelfth Amendment, when the next amendment to the constitution was enacted on 14 November 1987, it was numbered as the Thirteenth Amendment. That numbering has since been followed, enshrining the phantom Twelfth Amendment in the annals of constitutional history.”

Thirteenth Amendment (14 November 1987): To make Tamil an official language and English a link language; the establishment of Provincial Councils and the devolution of power to the provinces; reforms to Appeal Court powers; amendments to the Public Security Ordinance.

Fourteenth Amendment (24 May 1988): Extension of the president’s legal immunity; increase number of Members of Parliament to 225; the validity of referendum; appointment of Delimitation Commission for the division of electoral districts into electoral zones; proportional representation and the cut-off point to be 1/8 of the total polled; apportioning of the 29 National List members.

Fifteenth Amendment (17 December 1988): To repeal Article 96A in order to eliminate electoral zones.

Sixteenth Amendment (17 December 1988): To make provision for Sinhala and Tamil to be languages of administration and legislation.

Seventeenth Amendment (3 October 2001): To make provisions for the Constitutional Council and Independent Commissions, which includes the Election Commission, Judicial Services Commission and the Police Commission; amendments to the appointments made by the president.

Eighteenth Amendment (8 October 2010): To remove the limit to the re-election of the president and to propose the appointment of a Parliamentary Council that decides the appointment of independent posts like members of the election and human rights commissions and Supreme Court judges.

Nineteenth Amendment (28 April 2015): To annul the 18th Amendment and reintroduce the 17th Amendment that established independent commissions and limited the powers of the executive president; to limit the term of the president’s office to five years while the president continues to function as the Head of State, Head of Cabinet and Head of Security Forces.

The Proposed 20th Amendment

The proposed 20th Amendment to the Constitution has been in the pipeline for over two years since being introduced in 2018. The proposal was tabled in parliament by the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) with the explicit aim to abolish the executive presidency, which was weakened by the 19th Amendment.

However, the drafted reforms proposed by the government, which was gazetted earlier this month, are completely different from those put forward by the JVP.

The new Rajapaksa government has claimed that it will effectively repeal the 19th Amendment but retain some of its “salient features“.

According to Cabinet co-spokesperson Minister Keheliya Rambukwella, these salient features include the two five-year term limits imposed on the president.

A five-member committee composed of Rambukwella and Ministers G. L. Peiris, Dinesh Gunawardena, Nimal Siripala de Silva and Ali Sabry has been tasked with reviewing all Cabinet papers, notes and drafts already presented on constitutional reform. The committee is also responsible for proposing a panel of eminent persons to formulate a new constitution.

“[Constitutional reform] was in our election manifesto, it was clearly stated with regard to the 19th amendment. The public has mandated it,” Rambukwella noted in August.

Read more about the 20th Amendment and the reforms proposed here.