“Amazon promotes your book to people who are interested in them, based on your previous books’ performances. So the more you write, the more Amazon pushes it. It completely eliminates the need for agents, publishers, and everyone else involved.”

-Navin Weeraratne, author of The Hundred Gram Mission.

Getting published is no easy feat. It takes consistency, determination, a lot of luck, and a thick skin—the latter mostly to just keep going after getting rejected by publishers multiple times. Getting rejected (or published) isn’t generally an indication of how good you are as a writer—take J.K. Rowling for instance, whose rejection letters asked her to join a writing class.

Getting published in Sri Lanka is just as—if not—tougher. You will be well-sought after if your manuscript (or self-published book) won a national award or two, but it’s a series of rejections until then, especially if the writing isn’t a novel with the island as its focal point.

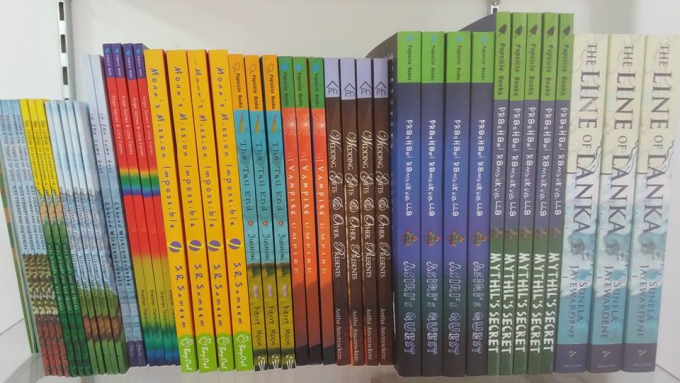

Taking these factors into account, several authors have turned to self and digital publishing to be met with unexpected success. The last two years alone have seen self-published Sri Lankan authors catapult to fame—both locally, and internationally. Roar Media spoke to a few niche authors, and Perera Hussein publishing house, to see what’s in store for Sri Lanka’s literary future (at least in English).

Why Self Publish?

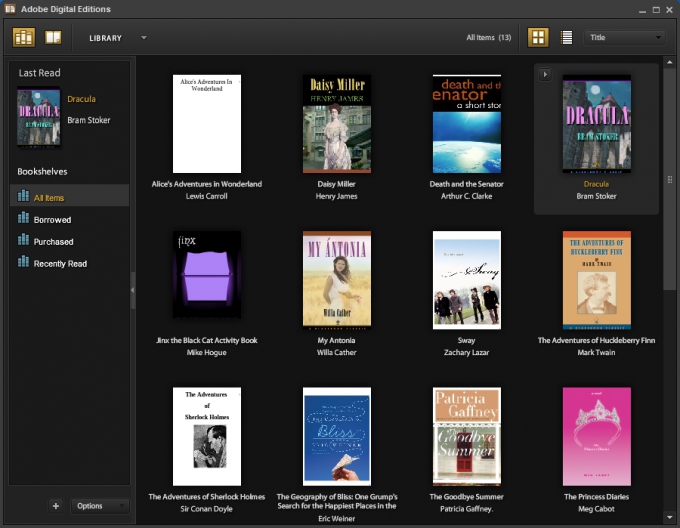

Local authors claim that self-publishing helps them connect directly with their readers, and get instant feedback, especially if they publish digitally. Image courtesy thedigitalreader.com

According to Weeraratne, it’s simply a lot less complicated and a lot more rewarding. This is more so as digital publishing literally pays you a larger percentage of profits from what the book makes, as opposed to traditional publishers.

“Amazon takes 30% of what you make, so you get to keep 70% of it. Traditional publishers, on the other hand, only give you 7% of the profits. With digital publishing, the more people like your books, the more you make—and Amazon keeps pushing your work to readers who are interested in your work, so you get marketed as well,” he explained.

The reason Weeraratne chose to publish online, he said, was because he rather incorrectly assumed that there was no scope in Sri Lanka for sci-fi, the genre he writes in.

Fellow sci-fi authors Theena Kumaragurunathan and Yudhanjaya Wijeratne echo this sentiment, though in their case, it was what several local publishers had told them when turning their manuscripts down.

Despite winning 2016’s National Literary Award, Kumaragurunathan’s book, First Utterance is difficult to categorise: is it poetry, prose, or drama? And what’s the scope for novellas—are there any readers? These were questions which discouraged publishers from accepting his manuscript.

“My luck with publishers went down to industry economics. Publishers usually focus on poetry, short stories, and novels. Up and coming authors have it a bit more difficult—I was asked to make everything in First Utterance prose, and publishers wanted changes I didn’t agree with,” he said.

The Pros And Cons

Literary events and festivals often bring self-published authors into the limelight. Image courtesy Daily Mirror.

After approaching both local and international publishers, Kumaragurunathan eventually decided to print the novella himself. Not having a publisher, however—for a printed book as opposed to an ebook—entailed a lot more responsibility and hard work; from designing, to the layout, proofing, editing, and marketing.

“You need to have a lot of time, and the work doesn’t end after you eventually publish—as a writer, you need to take care of both the online and offline marketing, which is difficult as most writers don’t have the know-how. You also need to be open to a lot of brutal criticism, and you need to make the editing process as rigorous as possible,” he stressed, concluding that one of the larger risks a self-publishing author has to take is the financial cost.

Conversely, winner of 2017’s National Literary Awards Amanda Jayatissa “didn’t think too much about the marketing angle”. Nor did she worry about overall design and layout as much: both being simplified thanks to digital tools.

“Publishing on Amazon is relatively simple: they give you guidelines on how to format it and lay the book out, so you already know what to do. However, having an agent gives you a bit more backing—ratings, reviews, and all that,” she added.

Her primary focus though was to just get the book out. Many agents she approached expected the novel to be about Sri Lanka—as opposed to steampunk, a completely new genre to the island. Having decided to publish digitally, the book immediately made its way to Amazon’s hot new book list within its first day of being published.

About Taking The Traditional Route

Getting published is always a big deal. Image courtesy facebook.com/gihanbookshop

“I’ve always told writers not to self-publish, but I think I’m wrong. Traditional or not, writing a book and getting it out there is really hard, but Yudhanjaya [Wijeratne] has proved all that wrong,” last year’s State Literary Award winner Nayomi Munaweera said.

Following multiple rejections from publishers in the USA, Munaweera approached Perera-Hussein publishers, where one of her two pitches was selected.

“After Perera-Hussein said yes, it got picked up in India and then publishing houses in the US got interested and had a bidding war. St. Martins gave me a two-book deal,” she said.

However, she advises new writers to have an established platform before self-publishing, and to ensure that what they write is really good else “it’s not going to do well”.

Meanwhile, co-founder of Perera-Hussein, Ameena Hussein, explained that publishers “bring a curated experience to readers”.

“Our criterion for publishing is simply a good story, related well. Our reading public or target market is Sri Lankans like us, who appreciate Sri Lankan stories or simply good books. Many authors approach us, unsolicited, with manuscripts. We read the manuscripts, assess them and publish the ones we feel will resonate and have a good readership. There are many manuscripts we reject. It’s purely subjective, I should add,” she said.

While Perera-Hussein publishes established authors like Yasmine Gooneratne and Carl Muller, they also publish new authors who then shoot to fame; Hussein cites Munaweera and Shankari Chandran as their most recent examples.

Speaking about how traditional publishing houses are affected by digital publishers like Amazon, she stated that most of Perera-Hussein’s books exist in electronic form as well.

“In some cases, we feel that e-books will do better for particular stories than printed books. This can also be a low-risk test mechanism, and if your story does well in e-format, you could consider a traditional book,” she added.

Finding A Balance

Wijeratne recently signed off a four-book deal with HarperCollins, one of the Big Five where English publishing is concerned. Despite this, he’s a strong advocate of self-publishing. While being signed on by HarperCollins means a lot to him as an author, his approach towards writing and publishing is the same.

“Whatever a publisher will pick up will go to a publisher. Whatever doesn’t will be handled by me,” he explained.

Jayatissa acknowledges the benefits of having an agent but does not foresee changing what she writes to accommodate what an agent or a publisher would require.

“If they refuse, I’m more than happy to just keep self-publishing,” she concludes.

Cover image courtesy of culturenorthireland.org