Nearly 10 years have passed since the end of Sri Lanka’s ethnic conflict—but the whereabouts of thousands of missing people are still unknown. Families, especially in the North and East, still continue to seek answers regarding lost ones.

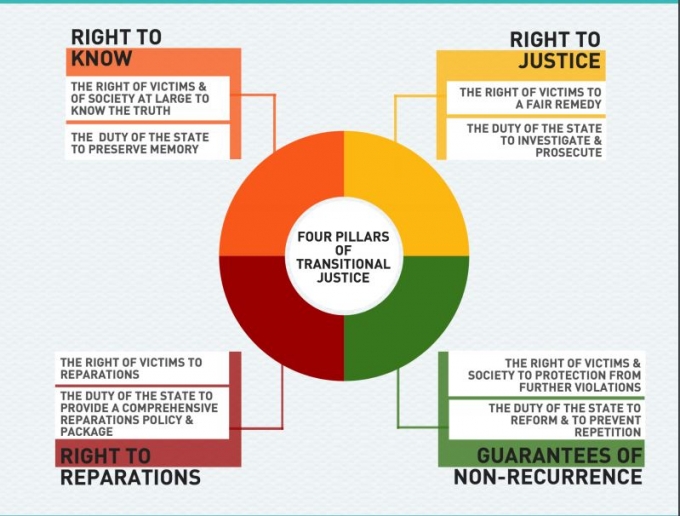

In an attempt to address these issues, legislation to establish an Office on Missing Persons (OMP) was passed in August 2016. This is one among four establishments recommended by a 2015 UN Resolution titled ‘Promoting Reconciliation, Accountability and Human Rights in Sri Lanka,’ and is part of the country’s transitional justice mechanism. For clarity, transitional justice is a set of judicial and non-judicial measures to address massive human right violations.

Graphic courtesy: cpalanka.org

Following numerous delays, the office itself came into being only this year, in March 2018.

Why Do We Need An OMP?

On 28 February, President Maithripala Sirisena appointed seven commissioners to serve at the OMP for a three-year period. President’s Counsel Saliya Pieris is serving as the Office’s first chairperson.

In an exclusive interview with Roar Media, PC Pieris highlighted the necessity of having an OMP, and of providing an answer to families of those who have disappeared.

It is estimated that at least 16,000 people have gone missing in the North and East. Of these, at least 5,100 are from the military. Likewise, there are several tens of thousands who have gone missing in the ’87-’89 conflict [which was the JVP insurrection], PC Pieris stated.

“One of the key objectives is to trace the missing. The law mandates that we have to establish a tracing unit, which would be empowered to investigate and enquire. There could be the involvement of experts, like forensic experts as well. The OMP will be given power to request courts to exhume or excavate [graves] as well,” he said, adding that apart from informing the relatives of the missing, the other mandate of the Office is to ensure non-recurrence of disappearances.

Criticism And Conflict Of Interest

“Each step of the process thus far to establish the OMP has been marked by slow progress, a regrettable lack of transparency, poor engagement with victims and troubling political actions to undermine the independence of the institution.”

– Ananda Galapatti and Professor Savitri Goonesekara.

Despite the Office on Missing Persons being the first of the four transitional justice mechanisms, and the only project which has made headway to date, civil society and organisations have a number of concerns. These include issues over ‘delays and errors’ in establishing and running the OMP, the lack of transparency in appointing committee members, and the conflict of interest in having the Office under a ministerial portfolio directly under President Sirisena.

Another major concern was the appointment of retired Major General Mohanti Pieris as one of the committee members. The move was condemned as being ‘most fundamentally insensitive’ by Tamil civil society activists as well.

When Roar Media highlighted these concerns, including how appointing a former military person could make the family members of missing youth in the North and East feel alienated, PC Pieris claimed that such perceptions were wrong.

“The missing and disappeared includes members of the armed forces. The commissioners represent a cross sections of professionals, civil activists, and more. The office represents a cross section of various stakeholders,” he reiterated, adding that where Major General Mohanti Pieris is concerned, there is no conflict of interest or cause for concern, especially given her contributions to humanitarian work.

Current Duties, Responsibilities, And Status.

Families of missing people have been protesting continuously for the last year in Kilinochchi, with intermittent protests before that in Colombo as well. Image courtesy: japantimes.co.jp

PC Pieris recognises the challenges ahead of him, and that it would take an indeterminably long time to address them.

Currently, the Office is still in its ‘embryonic stage’, where only the commissioners (and a secretary) have been appointed. Regional offices in the North and East are yet to be established, along with the required staff. He points out that both recruitment and procurement (of resources) will take time, given bureaucratic paperwork.

In addition to this, the OMP will also have to work with families of missing persons who do not harbour any faith in yet another government mechanism. President Sirisena had, at a meeting with the families of the disappeared last June, promised to release the list of names of those who surrendered to the military during the final stages of the war; his failure to follow up on the promise has further disillusioned the families seeking answers.

“We do realise that the families of those who are disappeared are skeptical of institutions established by the state, but the OMP will reach out to them and we will consult them on how we should proceed. We’ve already started discussions with some of the families,” Pieris said.

Meanwhile, the mandate of the OMP does not have any time restrictions. Neither does it restrict itself to investigating people who disappeared only during the civil conflict. According to PC Pieris, there are four categories of the missing and disappeared which falls under the OMP’s mandate. These are:

- Those who went missing in the aftermath of the North and Eastern conflict.

- Those who went missing during times of political or civil conflict in Sri Lanka—which includes the 1971 insurgency and similar instances.

- Those from the armed forces and police who are missing in action, and

- Enforced disappearances—including those of journalists and white-van victims.

The OMP is currently unable to state how long it would take to launch investigations and find answers as to what happened to the missing persons. However, they intend to begin with a central tracing unit in Colombo, and to include investigators in the regional offices which they hope will be established soon.

PC Pieris is confident about the office maintaining its independence, and remaining unbiased. When asked about the demands of families of the missing persons for international intervention, Pieris pointed out that there is very little an international body could do to address the issue.

“Practically, international intervention has always been very limited. That is not the answer to findings to the families of the disappeared. We need a strong, independent, domestic mechanism,” he said.

Government processes move at incredibly slow speeds. To date, it’s reported that seven women waiting for news of their disappeared family members have already died. Pieris states that the office has already started preliminary work. Hopefully, the remaining families will get closure soon.

Cover image courtesy: Reuters