The elderly man had not seen his family in 40 years. He is sometimes unable to correctly remember numbers. When asked how old he was, Sena Jenejasoriah said, “five-three”. Hospitalised for leprosy, an illness that was incurable a long time ago, Jenejasoriah is disabled, but no longer afflicted by the disease. But he has not been home since the day he was hospitalised.

Jenejasoriah is one of three patients receiving care within the crumbling walls of the Mantheevu Island Leprosy Hospital in Batticaloa. Secluded to an island and cut-off from the rest of civilisation, the hospital houses the country’s loneliest patients.

Jenejasoriah is from Beliatta, Hakmana— some 200 kilometres south of Batticaloa — and was nine when he was first diagnosed with leprosy. “When the wounds showed up on my legs first, my family took me to the Matara Hospital. I remember being admitted there. That was the last time I saw[them],” he told me.

According to Jenejasoriah, he was then transferred from the Matara Hospital to the Mantheevu Island Hospital. He remembers taking a bus to Batticaloa and then arriving at the hospital, where he would remain for the rest of his life. Today, 44 years after he was first hospitalised, a square room in the male ward, furnished with a single bed, a miserable mattress, a makeshift couch and a broken television set is what he calls home. Even the handful of clothes he wears were received through donations.

“I didn’t bring anything when I came here,” he said. I can’t remember exactly where my house is, and I don’t remember how to go there.”

Photo credits: Roar Media/ Kris Thomas

Deformity, Disfigurement and Disability

Leprosy—also known as Hansen’s disease after the scientist who discovered in 1873—has its roots in ancient civilization and is the result of an infection caused by Mycobacterium leprae, a close cousin of the bacterium that causes tuberculosis. The M. leprae that causes the disease evaded medical practitioners until the 1940s, after which a multidrug therapy was formulated and introduced to combat it. Depending on the severity of the M. leprae, a regimen of six to twelve months of rigorous treatment would be recommended.

Usually spread via droplets from the nose and mouth during close and frequent contact with untreated cases, leprosy is no longer as debilitating and horrific a disease as it was once thought to be—although it can lead to progressive and permanent damage to the skin, nerves, limbs, and eyes if left untreated. But the stigma was such in the past that patients with deformities and signs of having contracted the disease were segregated from society, which is how leper colonies came into being.

In pre-Independence Sri Lanka, the powers vested to hospital and government officials through the Lepers Ordinance No. 4 of 1901 saw the quarantine of patients into two leprosariums—the first built in Hendala in 1708 by the Dutch, followed by the one built by the British on the Mantheevu Island, in 1921.

As per the Ordinance ‘harbouring’ a ‘leper’ was not permitted, and Public Health Inspectors were allowed to ‘forcibly’ remove patients to be taken to a colony.

While the Ordinance has largely fallen into disuse, those affected by the archaic legislature remain outcasts with no families or homes to return to. And while Cabinet approval was granted to amend the Ordinance to allow patients at Hendala and Mantheevu leprosy hospitals ‘maintain social relationships’ in 2018, the Legal Draftsman’s Department told Roar Media, the amendments were still being drafted.

But the inmates at the leprosy hospital on Mantheevu Island are not the only incarcerated patients. “At the moment, there are 29 patients living out the rest of their lives at the Hendala Leprosy Hospital,” Dr Champa Aluthweera, Director of the Anti Leprosy Campaign of the Ministry of Health told Roar Media. The patients, many of whom share similar stories to Jenejasoriah and his fellow patients on Mantheevu Island, have no families to return to.

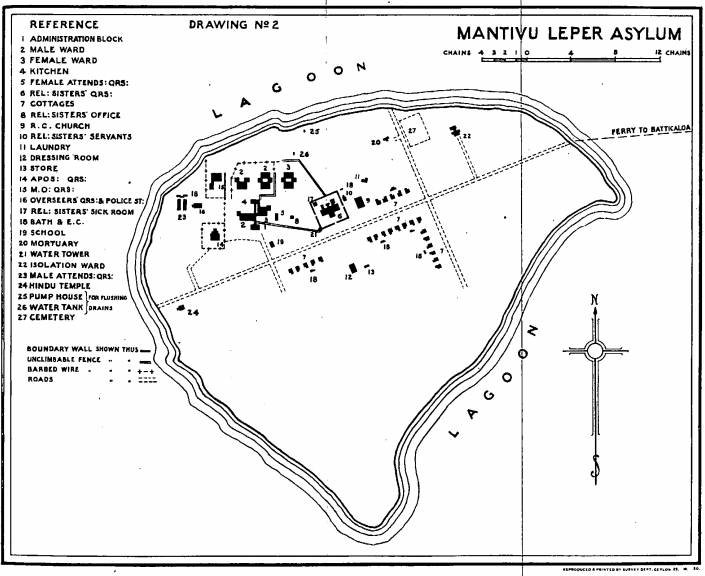

A Hundred-Acre Island

A report by architect, A. Woodeson for the Engineering Association of Ceylon, dating back to 1930, claimed that the hospital maintained over 10, 000 patients and managed twenty-four individual cottages, male and female wards, an administration block, an isolation ward, a dressing station, a laundry, a government school, quarters for the staff, and dormitories for the Religious Sisters of the Franciscan Order who nursed the patients. The hospital staff included one medical officer, two apothecaries, one overseer, 16 labourers and 16 attendants.

The survey report outlined: “The institution is a wonderful example of efficiency and cleanliness and reflects great credit on the Medical Officer and staff who are keen on their duties. The Medical Officer is a thorough optimist and the Religious Sisters are splendid examples of quiet unwearying devotion.”

Over the past 80 years, however, the situation at the Mantheevu Leprosy Hospital has changed for the worse. The land is thick with shrubs and imposing trees. Towering grass fields have invaded the paved road—now, diminished to a sandy walking path—from the small jetty to the hospital premises.

The cottages that once housed patients have been abandoned and are falling apart.

The wards are in a state of decay; the walls now brown with the constant bombardment of bird droppings [there are more birds on the island than people] and the walkways chipped off of its cement, exposing the brickwork underneath.

Apart from the one ward at the hospital which houses the three patients, only the haunted mansion-esque administration office, a grey water tank, an old church and a Hindu kovil stand.

Photo credits: Roar Media/Kris Thomas

‘There Used To Be Many…’

Ponniah Punnuthuraih is the oldest surviving patient at the Mantheevu Island Leprosy Hospital. At the age of 63, his mind is a patchwork of scattered memories—except for his first day at the hospital, when he was only five years old.

“There used to be many. I remember there were as many as 50 other [patients] here. But not any more,” he said.

Punnuthuraih’s room is similar to Jenejasoriah’s one: it contains one bed and a tiny cupboard in which he keeps his neatly folded sarongs and shirts, alongside his plate and cup. He is the only patient to own a working radio and a television set. “That’s how I spend my time; watching TV and listening to the radio,” he said. “I bathe. [And] I eat when the food is brought in.”

Like Jenejasoriah, Punnuthuraih has no home he can return to.

Photo credits: Roar Media/Kris Thomas

‘No Proper Rehabilitation’

Despite the World Health Organisation (WHO) declaring that leprosy was eliminated from the world in 2000, there has been an influx of new cases in various parts of the world. In Sri Lanka alone, Dr Aluthweera noted, approximately 2, 000 new cases are reported islandwide every year.

“The number of new cases [were] static over the years. Even so, 2, 000 new cases in comparison with a population of 21 million individuals, is still an alarming status,” she said.

However, none of those recently affected are subjected to the ostracism Jenejasoriah and Punnuthuraih faced when they were diagnosed. Most new cases, upon diagnosis, are treated and cured completely. Nevertheless, colonies which stood the test of time have endured, not only in Sri Lanka but also elsewhere in the world.

In India, there are approximately 700 active colonies, with self-imposed patients. Even the largest US sanctioned colony on Molokai, Hawaii, that shut its doors in 1969, continues to home six patients who chose to stay back.

In Sri Lanka, the 29 patients at the Hendala Leprosy Hospital will live out the rest of their lives there, with no home or families to return to.

Punnuthuraih says he would love to see his family even one more time, but he has no memory of how to get home, or even where his home is. “I have no land to my name, no money, and no skills. I can’t find employment. I don’t know anyone outside of the people here [on the island]. I’ve lived here my whole life. So why should I go back?” he asked.

Sri Lanka has no comprehensive programme of rehabilitation for the many disabled leprosy patients. At present, the Mantheevu Leprosy Hospital comes under the administration of the Batticaloa Teaching Hospital, but when asked why the three patients of the Mantheevu Leprosy Island continue to live isolated lives, Hospital Director Dr Kalaranjani Ganesalingam said: “The patients have not been relocated elsewhere due to the instructions received by the Ministry of Health. The instructions came in during the tenure of my predecessor. I have not received further instructions that said otherwise.”

While Dr Ganesalingam, in her capacity as a medical practitioner accepted that the patients require rehabilitation and reintegration into society, she noted cryptically, “Whenever and whatever they [the patients] need, we [Batticaloa Teaching Hospital] provides.”

However, Former Director of the Batticaloa Teaching Hospital, Dr Ibra Lebbe told Roar Media there had never been any instructions from the Health Ministry relating to the conditions of the patients at the island hospital.

“It is up to the Ministry to make a decision to relocate the patients elsewhere. However, the matter was never discussed during my tenure. There are institutions that can coordinate these discussions—they have all the rights to do so. [But] Even during my tenure, there was no proper programme to rehabilitate these patients,” he said.

So what do these patients make of each other? For Jenejasoriah and Punnuthuraih (and their absent inmate), life outside the island is impossible to imagine. They are unsure of their ability to live within a community.

It was Jenejasoriah, who took my notebook in his stubby misshapen fingers and scribbled nonsense to show me he could not remember how to write, who put it best.

“Even if I go home, even if I find them [family] I’m afraid they will not take me back. They will hate me.”