Across the largest Gulf State, more than hundreds of Sri Lankan workers wait in hope to return home. It has been over three months since the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a COVID-19 pandemic, but none of the stranded workers in Saudi Arabia have yet been repatriated.

Malini* (45) has worked in a number of countries in the Middle East for around 20 years. Now in Saudi, she is employed as a housemaid and undertakes the cooking, cleaning and general upkeep of a large family.

She was recently diagnosed with a cyst in her womb, for which she must soon undergo surgery. “It’s been difficult as I bleed occasionally, and some days are worse than others,” she told Roar Media.

Widowed for 13 years now, her three children want her back during the crisis. She, too, longs to be home with them, preferring also to have her surgery in Sri Lanka, with her family around her.

But she has not been able to return home. “My employer got me the number to the Sri Lankan Embassy in Saudi and I called to explain my situation,” she said. “But when I spoke to a representative I was told that if I had been able to bear the pain the last few months, why can’t I just bear it for longer?”

Stranded

Sri Lanka first began repatriating citizens in March, with a particular focus on students, facilitating flights from countries like India, the United Kingdom, and Australia.

Secretary to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Ravinatha Aryasinha said in April over 27,000 Sri Lankans overseas—including 17,000 migrant workers—had expressed a desire to return home, but focus would be on repatriating students and those on government training, considering the ‘particular vulnerability they faced from a medical perspective’.

However, with increasing pleas from migrant workers stuck in the Middle East, repatriation also began for those in Qatar and Kuwait. A public outcry over pregnant mothers stuck in Dubai led to a special flight on June 18 which repatriated 290 Sri Lankans, including 120 pregnant mothers.

But as each repatriation flight brought in more and more infected cases—flights in May led to a fifth and ongoing patient cluster—fear that healthcare resources could be overburdened has led to authorities delaying some repatriation flights, leaving many migrant workers stranded.

Shehan* (29) is an engineer who has been working in Saudi Arabia for five years now. Planning to join a new organisation, he informed his employers that he would leave in early March. However, the pandemic hit, borders closed and all hope of travel gradually ceased, not a few days after he handed in his resignation.

Earlier, in December, his wife had travelled back to Sri Lanka to spend the initial months of her pregnancy with family to support her. He had intended to join her in March, until they could both leave again for Dubai, where the new job awaited him. But he could no longer do so.

“I never thought I would be stranded in Saudi with no income for months on end,” Shehan told Roar Media. “This is a special time for us, it is also a complicated pregnancy, and I wanted to be there for my wife.”

When Shehan contacted the Sri Lankan Embassy in Saudi he was advised to immediately ask the organisation he was still attached to, not to process his final exit visa, because if they did and he had not left the country within 60 days he would be compelled to make a penalty fee.

“This could [have] even affected future attempts to come back to the country,” he said. “In my case, I was precautioned by the Embassy and my company agreed to hold back. But this was not so for everyone, and many who are stuck here are running out of their buffer time.”

In Foreign Land

“There are roughly 135,000 Sri Lankans in Saudi right now, with around 128,000 making up the working population,” Madhuka Wickramarachchi, Charge d’Affaires at the Sri Lankan Embassy in Saudi Arabia told Roar Media.

Wickramarachchi said six Sri Lankans had fallen victim to COVID-19 in Saudi, “But, they were all above 60 years of age, and had other underlying health issues,” he added. According to him, 30 Sri Lankans in Saudi had been infected by the virus, of which 20 had already recovered, and 10 are still in hospital.

In June, the Sri Lanka Bureau for Foreign Employment (SLBFE) reported that 23 Sri Lankan expatriates had died of COVID-19 in the Middle East, from mid-March to date, including in Saudi.

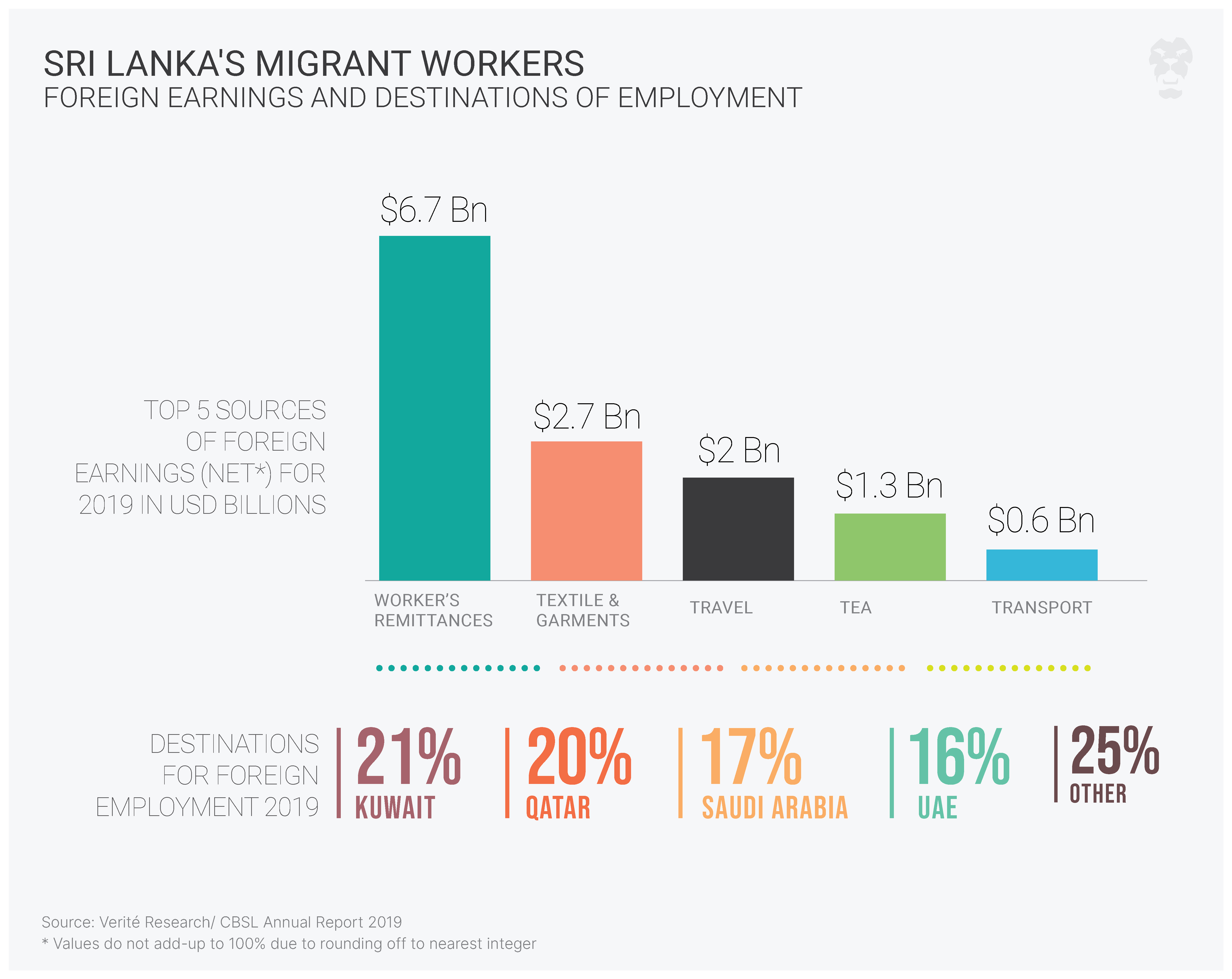

Sri Lankan workers have had a long-standing relationship with the Middle East having travelled for work from the 1970s. Since then, the Government has continued to encourage migration, especially of domestic workers, this considered at the time a strategy towards solving severe unemployment and alleviating poverty. Their remittances are still the largest contributor to foreign earnings in Sri Lanka today.

In 2019, foreign worker earnings brought in 6.7 billion USD, and according to think tank Verité Research more than 75 percent of migrant workers are in the Middle East.

“In Saudi, the majority of workers are domestic workers, which includes housemaids, drivers, gardeners, and helpers,” Wickramarachchi said.

Saudi Arabia recorded its first case on March 2 and set in place curfew hours and subsequent lockdowns in certain areas by March 23. Two months later, in late-May, the country began to ease its lockdown. It is, however, currently battling a second-wave of COVID-19 infections, as coronavirus cases hover between 3,000-4,000 daily. Considered one of the hardest-hit Arab countries, Saudi had surpassed 180,000 confirmed cases and 1,551 deaths, at the time of writing.

The country’s large landmass had made it more difficult to reach out to Sri Lankans residing there, Wickramarachchi explained. However, he added that the Embassy had worked hard to get in contact with, and aid as many Sri Lankans as they could by setting up a hotline, distributing rations and sending tokens to workers in more remote areas through WhatsApp, which would enable them to obtain basic necessities.

The Sri Lankan Government announced that it has sent Rs. 42.6 million to Sri Lankan Missions in the Middle East and elsewhere, for basic rations, medicines and safety equipment. While, Wickramarachchi confirmed that the Embassy in Saudi received around Rs. 1.075 million from government sources.

One other major challenge the Embassy is dealing with is facilitating Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) tests for workers before they leave, which would incur quite a cost. According to Wickramarachchi the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has set up free testing for nationals and residents. But, it is still prioritised for those with symptoms, leaving many without recourse. He added, however, that Sri Lanka authorities are in negotiations with the Saudi government to conduct at least 1,000 tests for workers.

To Return

“We keep hearing about flights from other countries and people going back, while we have heard nothing definitive over the past months,” Shehan said.

In desperation, a group of stranded Sri Lankans had earlier emailed the Sri Lankan Ambassador in Saudi Arabia, giving details of those already on exit visa status and confirming the fact that these workers are willing to pay for their tickets and for quarantine centre facilities. But, they are yet to receive any response.

For both Shehan and Malini, the hardest part has been months of waiting and not knowing. Shehan in his apartment alone, Malini at her employer’s house, one of the many foreign domestic help.

“This has been the most difficult time in my life,” Shehan said. “In addition to money, I have struggled mentally during this time, and I’m feeling so depressed. But I know people who have it worse, who cannot even afford to have three meals,” he said.

A video posted to Facebook on June 6 showed five Sri Lankan workers stranded in what was described as a 10 x 10 room in Saudi Arabia. These workers were not in possession of masks or gloves, had no work, were struggling to find food and were begging to be repatriated.

In the video, the workers talked about the harsh conditions they were dealing with, having to bathe using a bidet in the one bathroom. They also claimed they had not received any rations and could not contact the Embassy—“they just cut our calls,” one of them said.

Video posted on Facebook on June 6 shows Sri Lankan workers stuck in Saudi Arabia telling their story.

Workers in the Middle East fall under the kafala system of sponsorship-based employment, recognised as highly exploitative. There is a long, documented history of discrimination, abuse and even death at the hands of the Saudi government or employers.

Wickramarachchi explained that while it was the United Arab Emirates (UAE) that had the most number of migrant workers from Sri Lanka, followed by Qatar and Kuwait, and then Saudi, “the decision to repatriate citizens lies with the Sri Lankan government”.

He further added that while there are plans for a repatriation flight that could accommodate 290 people in July, there has been no official confirmation of this. At this juncture, the Embassy is only gathering information on the people who may want to leave.

Shehan has received a call asking for personal information and telling him what the flight will cost, but Malini has not been communicated with, at all.

“I am not here because I like it,” Malini said. “We have suffered and struggled and come here, and I have nine people depending on my salary. I am still in a foreign country, and isn’t the Embassy supposed to be our representative? Why isn’t anyone doing anything?”