“February 3 midnight. As the clock’s hands veered to a minute past, the burst of crackers heralding the ‘appointed day’ for Lanka’s independence crashed into the silence of the night.” – Ceylon Observer, February 4, 1948.

Thus began celebrations to mark Ceylon’s long-awaited independence from the British. At 7:30 the next morning, in a ceremony held at the Queen’s House, Sir Henry Monck-Mason Moore was appointed Ceylon’s first Governor-General to the ringing sounds of a gun salute. Later that day, the lion flag was hoisted at a ceremony at the Assembly Hall at Torrington Place, signalling Ceylon’s new status as a free country.

“I very vividly remember the Union Jack coming down, and the Lion Flag being hoisted,” said 96-year-old veteran journalist, editor and author, Kala Keerthi Dr. Edwin Ariyadasa. Although only an undergraduate at the time—too young to be an active participant in the independence movement— he said “[we] knew that we were participating in an important historical event.”

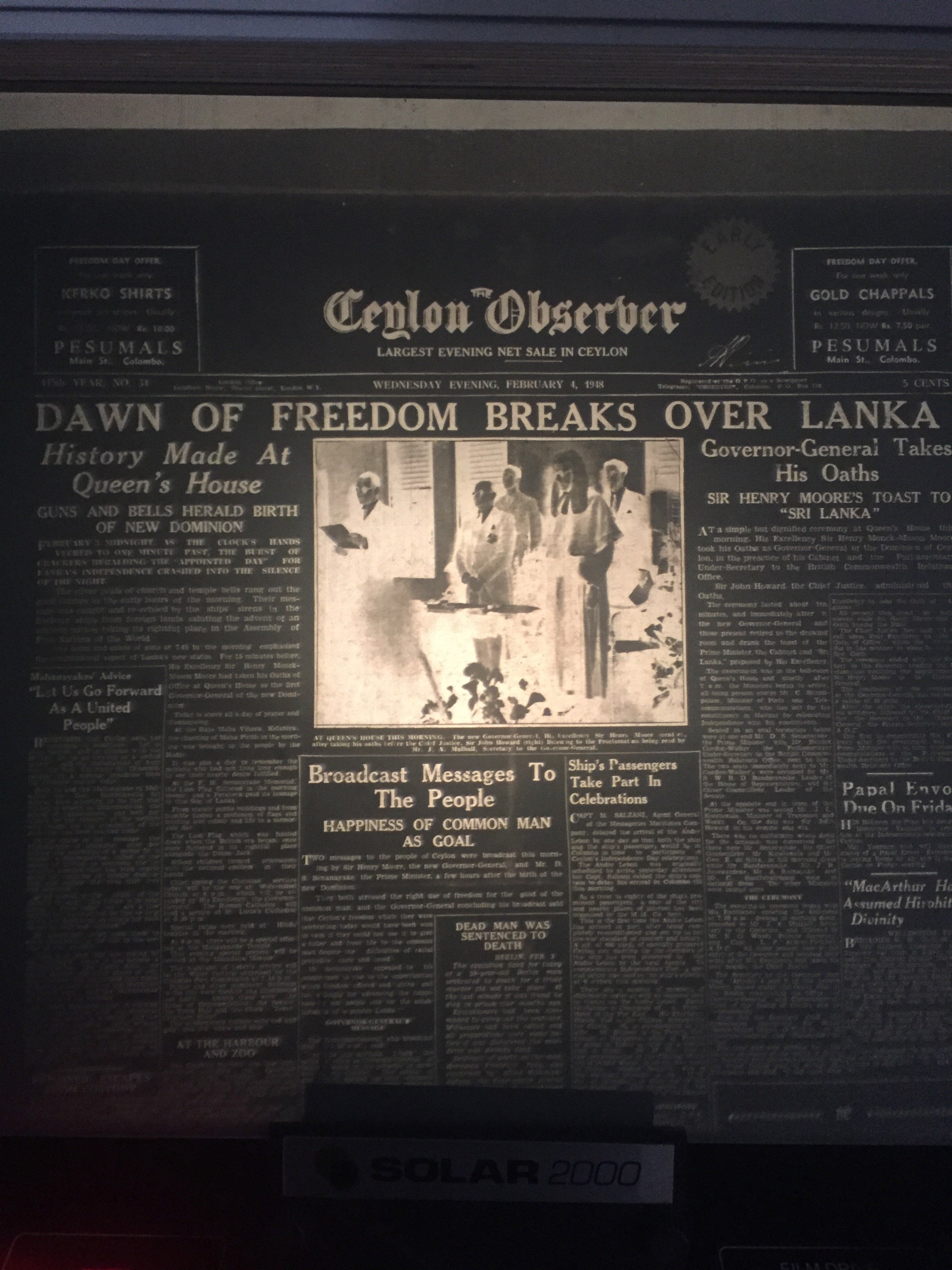

The newspapers the next day were filled with reports of the celebrations that took place on February 4. Under the headline, ‘DAWN OF FREEDOM BREAKS OVER LANKA’, the Ceylon Observer evocatively described the ‘silver peals of church and temple bells’, that were ‘re-echoed by the ships and sirens in the harbour,’ as Ceylon took its ‘rightful place in the Assembly of Free Nations of The World.’

Reflecting on his memories from that day 71 years ago, Dr. Ariyadasa said he had shared the sentiments of most people in the country at the time. “We wanted independence, our own rulers,” he said. Recalling the jubilant crowds that thronged to the city to watch the ceremony, he said, “The people were crowded as far as I could see. There was a certain amount of rejoicing at that moment.”

Several events were organised for that day: a morning mass at the Cathedral Church in Mutwal, maha pirith at the Raja Maha Viharaya in Kelaniya, and the highlight of the evening — a ‘Water Festival’ organised for the public by the Colombo Port Commission.

“Long after midnight, thousands flocked to Fort for illuminations and the water pageant. Colombo was robed in splendour, with gaily decorated streets, pandals, flood-lit buildings and a riot of vari-coloured illuminations,” said the Ceylon Observer, describing the occasion.

In his address to the nation, Prime Minister D. S. Senanayake called upon his countrymen to “transform this newly-won freedom into an instrument of happiness for the people, prosperity for the country and advancement of peace in the world,” describing the attainment of political freedom as “second in importance only to the message of spiritual freedom delivered by the Lord Buddha.”

However, Dr. Ariyadasa said the focus of the people were elsewhere: “We had only one particular thing in mind — taking it over from the British. That we were repossessing our heritage, getting our kingdom back for ourselves. Other details did not quite matter at that point,” he said.

A Lack Of Vision

Perhaps it is this conspicuous lack of vision that has led to the current vacuum in the body politic. Trade unionist Peter D’Almeida, (61), questioned the very meaning and impact of independence from the British.

“Freedom from what?” he asked. “Because we just passed on the rule from British capitalists interests to Sri Lankan capitalist interests.”

Although he acknowledged that there was certainly a movement across all of Britain’s colonies to overthrow British imperialism, quoting Colvin R. de Silva, a founder of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party, the first Sri Lankan Marxist political party, he described the events of February 4, 1948 as a “bland moment” for all but those involved in the struggle.

“And it was not a big struggle in Sri Lanka. We got it because of the struggle in India,” he said.

D’ Almeida said that despite 70 years of independence, Sri Lanka had continued to retain “the worst of British institutions”— a parliamentary system “that has failed us”, an education system geared to “churn out people for the industrial age” and other forms of governance that were not the “best for us.”

Highlighting the fact that the recently inaugurated Matara-Beliatta was the first built since the British ceded power to Sri Lanka—and that too, with funds provided by the China Exim Bank—he said, “Seventy years later…we are completely dependent on foreign nations…and we have replaced British colonialism with Chinese imperialism.”

“So, I don’t know if throwing out the British made a change to the aspirations people had of a different type of society,” he said.

Money Matters

Pesala Karunaratne (34), President of the Colombo Chapter of the Young Professionals Organisation (YPO) of the United National Party (UNP), was also critical of Sri Lanka’s dependence on foreign nations.

“The way I see it, independence is to be able to act as a sovereign nation, to operate without interference,” he said. “But instead, we have become economically dependent. And as a result, we are still ruled by the conditions imposed on us by other nations.”

Pointing out that Sri Lanka had no competitive advantage as a country, and hence, no bargaining power in the world, Karunaratne said leaders needed to look for long-term solutions to the issue.

“Today we are reliant on the Chinese; sometime ago, we were reliant on the West,” Karunaratne said. “We need to train our labour for tomorrow’s industries. Policymakers must be able to assess what industries will be in demand in the next five or so decades, and adjust our education system to produce that market-ready labour,” he said, warning that unless this happens, Sri Lanka would continue to be dependent on other countries.

A Sense of Responsibility

“In terms of our generation, independence wasn’t hard-fought; it wasn’t hard-won by us. It was more of a legacy, an endowment, part of my inheritance,” said Manisha Dissanayake, a 25-year-old lawyer and the founder of The Arka Initiative, an organisation that works to support to men and women on issues surrounding sexual and reproductive health.

While some of her earliest memories are of colouring in a black-and-white picture of the flag, which was later tacked to a waving ekel stick, it was only later, as she became more socially and politically conscious, that Dissanayake began to understand the true meaning of independence.

“I really started to understand that independence was not this abstract concept, but rather, something that thrusts upon us a certain obligation and accountability, to make something of what we have gotten,” she said.

In determining what contribution her generation could make to taking Sri Lanka forward, Dissanayake feels the youth is positioned to play a specific role — “to bring something fresh to the table…to breathe new life into stagnated conversation, into certain prejudices that haven’t gone away.”

Although declining to assess how well Sri Lanka had done since independence was granted, considering it a “difficult question that can’t be arrived at through a quantitative assessment or a balancing exercise,” Dissanayake advocated for a “culture of service” and more youth engagement to overcome any deficits.

“We need to foster a culture of service,” she said, “to individuals, the community and our country. The moment that young people feel a sense of responsibility, I think that’s when we can really start to move.”

.jpg?w=600)