Ihthisham Lye (27) felt a pain in his throat the moment he stepped out of the airport, after returning from a business trip to Malaysia on March 4. He recognised the signs of oncoming fever. “My wife was worried because the antibiotics I took did not work,” he told Roar Media.

With COVID19 fears at an all-time high, Lye had himself admitted himself to the National Infectious Diseases Hospital (IDH) in Angoda, where a majority of the suspected and confirmed cases are being treated, for testing.

“My wife was anxious until the results came out. It was negative. It was quite a relief for our families. Everyone was worried,” he said.

Although Lye was in the clear, doctors at the IDH instructed them both to strictly adhere to two-weeks of self-quarantine, as the possibility of symptoms developing later was very real.

What Is Self-Quarantine?

What self-quarantine, or self-isolation entails has been subject to much speculation. In essence, it is a set of rules applied to a large number of healthy people, to ensure no one else in your family, or environs, are infected with the virus, that you may have potentially been exposed to.

Those in self-quarantine aren’t necessarily sick. However, since most of them have returned from abroad and COVID-19 has spread globally, they could develop symptoms of the disease within 14 days of returning.

People who may have been in contact with someone in Sri Lanka, who have subsequently tested positive for COVID-19, are also advised to enter self-quarantine, where they are monitored for any developing symptoms.

In the barest of terms, while in self-quarantine, you cannot leave your room or residence. You are not allowed to interact with your family and you spend your days all by yourself.

As per the home quarantine guidelines drawn up by the Epidemiology Unit of the Ministry of Health, those in self-quarantine must:

- Stay indoors for 14 days (later, this was extended by a week, bringing the total to 21 days). This is to prevent community transmission

- Use a well-ventilated room, separate from the rest of the household

- Maintain at least one-metre distance from family members/other people

- Use a separate toilet if possible (if shared, the toilet must be cleaned regularly, and this includes taps, doorknobs and utensils with soap and water

- Be sure to use separate towels, bedding, cups, plates, etc.

- Have towels, bedding other linen washed separately

- Not entertain visitors

- Wash hands well and regularly, for at least 20 seconds with soap and water and also maintain alcohol-based hand hygiene in instances where hand washing facilities are inadequate

- Avoid touching eyes, nose and mouth with unwashed hands

- Monitor body temperature twice a day.

- Dispose of any used face masks and gloves in a closed container

According to Dr Sumudu Hewage, a Community Physician attached to the Ministry of Health (MoH), the best way to go about this, was to act as though you may be potentially infected. “You [will be] doing a service to the rest of the society by staying at home and stopping the spread of this disease,” she said.

Home Vs A Quarantine Centre

When Areeb Thassim (20) was first instructed to self-quarantine, he was relieved. A medical student in the Netherlands who arrived in the country in early March after a transit in Dubai, he had initially been told he would be taken to a quarantine centre, along with several others.

“We were taken to a separate building within the airport premises, where we were sprayed with disinfectants. They made us sign some forms and put us in a room, with a bunch of buses waiting outside. Nothing was initially communicated to us. With no food or water for over three-and-a-half hours, people became pretty panicked,” he told Roar Media.

They were, however, finally let go under strict instructions to self-quarantine. “Everyone was more than happy to do that,” Thassim said, although he has found the period of isolation less than appealing. “It has been really boring. I do see my family around the house from a distance. But I sleep most of the day now because I’ve really got nothing else to do.”

As part of its clampdown against COVID-19, the government opened in quick succession 44 quarantine centres across the country. Operated by the tr-forces, the quarantine centres housed in excess of 3, 000 returnees from ‘high-risk’ countries, like Iran, Italy and South Korea, and later, India and Europe as a whole. But numbers have since reduced as more and more leave having completed their two-week period in quarantine.

All others returning to Sri Lanka were instructed to self-quarantine at home, under the supervision of Public Health Inspectors (PHIs).

These PHIs, assigned by the MoH, conduct daily monitoring throughout the 14-day quarantine period, whether through personal visits, telephone inquiry or SMS.

If symptoms develop, PHI officers inform the MoH and regional epidemiologist, and transfer the patient via ambulance to the nearest designated hospital.

“In the last week, the police came to check on me twice,” Thassim told Roar Media. “I’ve [also] received two phone calls from them and [from] officers of the MoH. They didn’t physically see me, they just wanted to make sure I was at home and wasn’t displaying any symptoms, which they asked my father about. No one came into physical contact with me.”

Until Entirely Eradicated

Thassim’s 14-day quarantine period is coming to a close soon and he cannot wait to leave his room.

“It’s definitely gotten lonely. A couple of days are okay but knowing you don’t have a choice is worse,” he said.

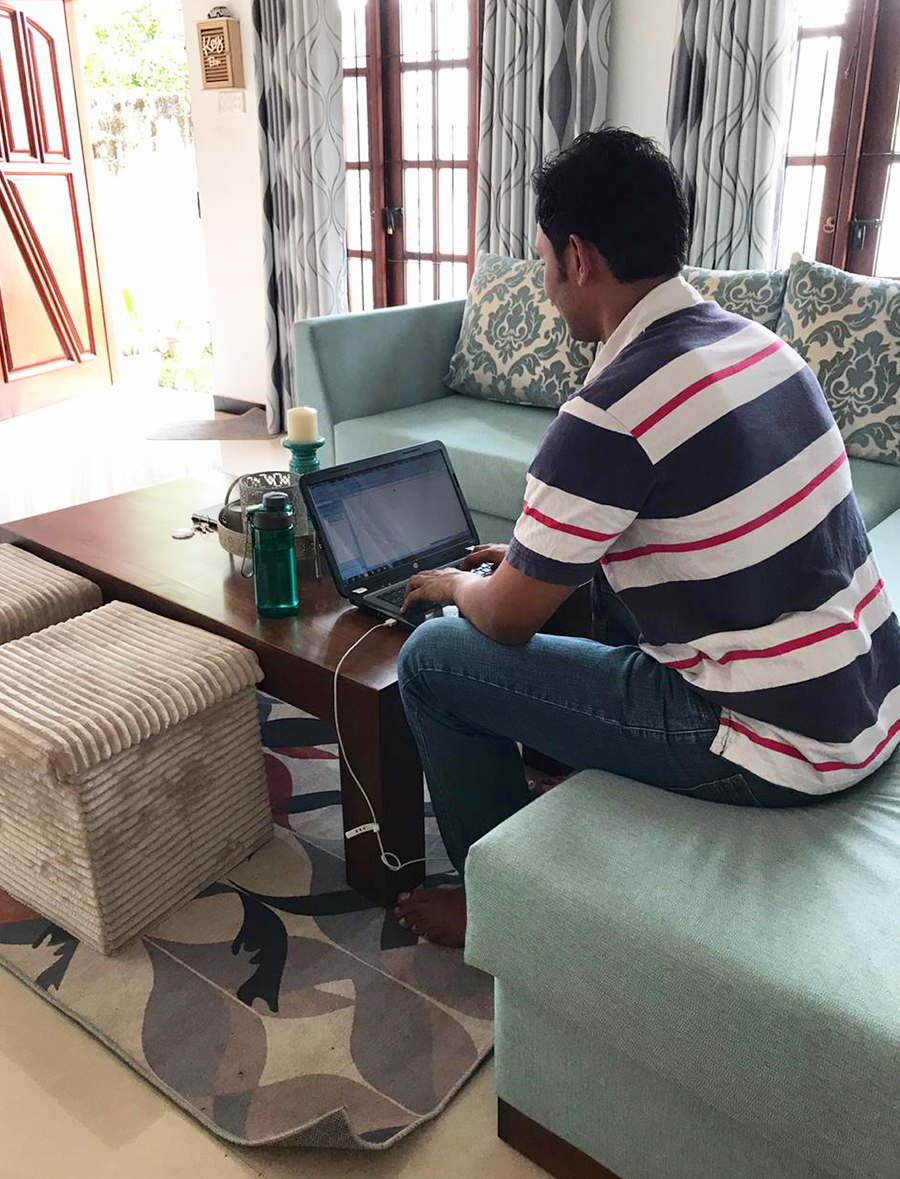

To pass his boredom away, Thassim spends most of his day in front of the laptop or on his phone, studying, working, watching movies or video calling his friends.

“I eat alone in the kitchen where the meals are set up and kept ready for me. I work out a little in my room sometimes, but to be honest, it’s really hard to motivate myself to do much. I take a walk because staying in the room all day, I think would probably kill me,” he said.

It’s different for Lye. For a person whose time is mostly spent on travel, the self-quarantine period has been a welcome change in pace in which he finds solace.

“It’s actually good for me this time during the quarantine. My wife and I get to spend more time together. We usually don’t get to see each other this often because we both work full time,” he said.

This COVID-19 crisis is far from over in Sri Lanka. Each day new cases are reported and more people are moved into quarantine centres or advised to self-quarantine based on exposure. Until this affliction is completely eradicated, we must do our part, however difficult it is to limit the spread of the virus and to protect our loved ones, community, and country.

.jpg?w=600)