Before the late 1950s, books rarely appeared in colour, because of high printing costs. Then, the German-Polish-British publisher Paul Hamlyn struck a deal with Artia, a state-controlled publishing house in Czechoslovakia (then in the so-called Eastern Bloc), which had high-quality but low-cost, four-colour presses. As a result, not only did Hamlyn bring out a whole series of legendary British-authored books, such as Marguerite Patten’s Cookery in Colour, but also English translations of Czechoslovak books.

One such book was The Monkey King, a translation from the Czech by George Theiner of a compilation of stories from the Ming Dynasty Chinese author Wu Chengen’s Journey to the West (Xi You Ji), containing beautiful, sinoesque illustrations by Zdeněk Sklenář—recently returned from China.

Media Icon

This book had its greatest impact in Czechoslovakia, where it inspired a play, Monkey Sun and a more recent audio-play on CD. However, these represent merely a fraction of the literary, artistic and dramatic works about the legendary Sun Wukong, the Monkey King.

Apart from the Hamlyn book, there were many translations or retellings of Journey to the West, the most notable being an English translation by Arthur Waley and Anthony C Yu’s complete translation. It also inspired the science fiction writer Cordwainer Smith’s only novel, Norstilia, as well as a host of graphic novels, giving birth to almost an entire genre of art.

The story inspired a further six stage plays, including two musicals, and an astonishing 30 films to date. It also spawned a no-less-amazing 14 television series, including an international co-production released this January, The New Legends of Monkey. The creators of the ‘genre-bending’ television series Into the Badlands, Alfred Gough and Miles Millar, based it loosely on Journey to the West.

The Monkey King also features in online video games, such as Oriental Legend, League of Legends and Enslaved: Odyssey to the West.

Xuanzang

The core of the tale lay in the real-life adventures of the Tang era Mahayanist scholar-monk Xuanzang (c. 600-664), who set out from the Tang capital Chang’an (modern Xian), and travelled through Central Asia along the Silk Road to India. The 17-year-long journey, as much a pilgrimage as an exploration, took in the Mahayanist Fifth Buddhist Council organised by the Vardhana emperor Harsha at Kanauj (in north India), as well as the main Buddhist sites, ranging from Bamiyan in modern Afghanistan to Kanchipuram in modern Tamil Nadu.

From Tamil Nadu, he intended to follow in the footsteps of Faxian to Sri Lanka (Sang-Kia-Lo or Sinhala), at the time considered a sort of Buddhist superpower, but news of calamities in the island caused him to desist. Nonetheless, he included a long and illuminating description of the island in the encyclopaedic Great Tang Records on the Western Regions (Dà táng xīyù jì), which he wrote for the Tang emperor Taizong.

Xuanzang returned to China bearing 657 Sanskrit Mahayana and Theravada texts, as well as seven Buddha statues and more than a hundred relics. In order to house these, having been made abbot of the Da Ci’en monastery in Xian, he obtained the permission of the the Tang emperor Gaozong to build the new Giant Wild Goose Pagoda inside. He translated and wrote commentaries on many of these texts, earning for himself the nickname Sanzang Fashi (teacher of the Tripitaka Dharma).

Mahayanist Epic

Wu Chengen, a jaded mandarin in the Ming civil service, retired to his hometown Huai’an, in Jiangsu province, where he devoted himself to writing prose and poetry. He included a fair amount of the latter in his novel, Journey to the West, which in opposition to the classical style of writing favoured by authors at the time, he wrote in the “vulgar tongue” or the language of the common people. His literary sources were similarly common: he drew upon a wealth of folklore surrounding the legend of the Monkey King, which he interpolated into historical material. Around the bare bones of the tale of Xuanzang’s expedition through central and south Asia, Wu Chengen built up the quintessential Mahayana Buddhist epic.

Very little of the factual historical material remains. Journey to the West must be seen principally as an allegory—and, in part, a satire on Ming Chinese society, state and clergy. Not even the celestial bureaucracy, portrayed as a caricature of its earthly imperial counterpart, is spared his cruel wit. This irreverence—in stark contrast to the conventional Confucian values of the other classics—appealed to the followers of Sun Yat Sen (such as the scholar Hu Shih, later Chinese ambassador to Washington), as conferring the authority of tradition to the new, revolutionary ideologies. This played no small part in the global diffusion of its popularity.

Ancient Superheroes

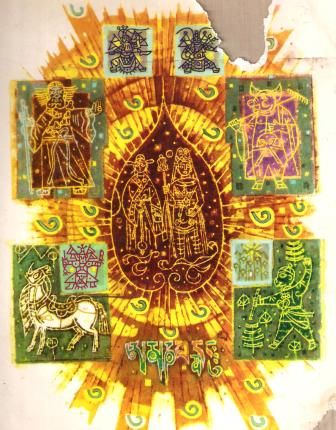

The story tells of a ‘stone monkey’, born of a union between Earth and Wind, who becomes the monarch of the monkeys inhabiting the ‘Mountain of Many Flowers’. Gaining from a Taoist sage the name Sun Wukong (or ‘monkey who understands emptiness’) and the knowledge of immortality, he wreaks havoc in Heaven. The Buddha subdues him and imprisons him under a mountain of five elements, but the goddess Guanyin (Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara) promises his freedom if he escorts a Chinese monk, Tang Sangzan (Tang master of the Tripitaka), to the ‘Western Paradise’ to obtain the Tripitaka canon from the Buddha. Together with Pigsy (a pig spirit), Sandy (a water spirit) and a dragon/horse, Sun and Tang Sangzan have many adventures before accomplishing their task.

The character of Tang Sanzan (rendered as Tripitaka in translations), while pure and kind, is far from that of the brave and resolute Xuanzang. He is portrayed as being whiny, small-minded, sluggish, and lacking in judgement. He must be saved constantly by his disciples, a Lois Lane to their collective Superman. However, these old-time superheroes lack the fascistic perfection of their 20th century comic-book counterparts, being prone to anger, alcohol, gluttony and lust.

Why Monkey?

How did Sun Wukong come to be the central character of the epic? Indeed, how did he come to figure in it at all?

One school of thought, epitomised by Meir Shahar of Harvard University, sees a link between Journey to the West and a mythological corpus of scripture and folklore surrounding Lingyin Si monastery in Hangzhou. The monastery, founded by an Indian monk, Huili or Matiyukti, on Feilai Feng mountain, came to be associated with gibbons, who co-existed with the monks living in the caves and grottoes that dotted the mountain. Very early, legends began to spring up about magic monkeys, which bore parallels with the Sun Wukong legend. Feilai Feng bears a resemblance to the ‘Mountain of Many Flowers’.

Lingyin Si is Chinese for Vulture Peak, the name of the mountain (Gijjhakuta or Gṛdhrakūṭa), near Rajagaha in Bihar, where the Buddha expounded his doctrine. Vulture Peak transformed itself in Mahayanist belief into a kind of heaven, and in Journey to the West, Tang Sangzan and Sun Wukong attain Buddhahood on this mountain. An early legend held that Huili and a monkey disciple went in the opposite direction, from Rajagaha to Hangzhou, where they recognised Feilai Peak as Vulture Peak, which had followed them through the air. Feilai Fang means ‘the peak that flew here’. The story of Huili’s monkey is so similar to the later legends of Sun Wukong that there must be a link.

Hanuman

However, another school of thought, starting with Hu Shih, considered that the mythological South Asian monkey deity Hanuman, might have been the origin of the Sun Wukong legend.

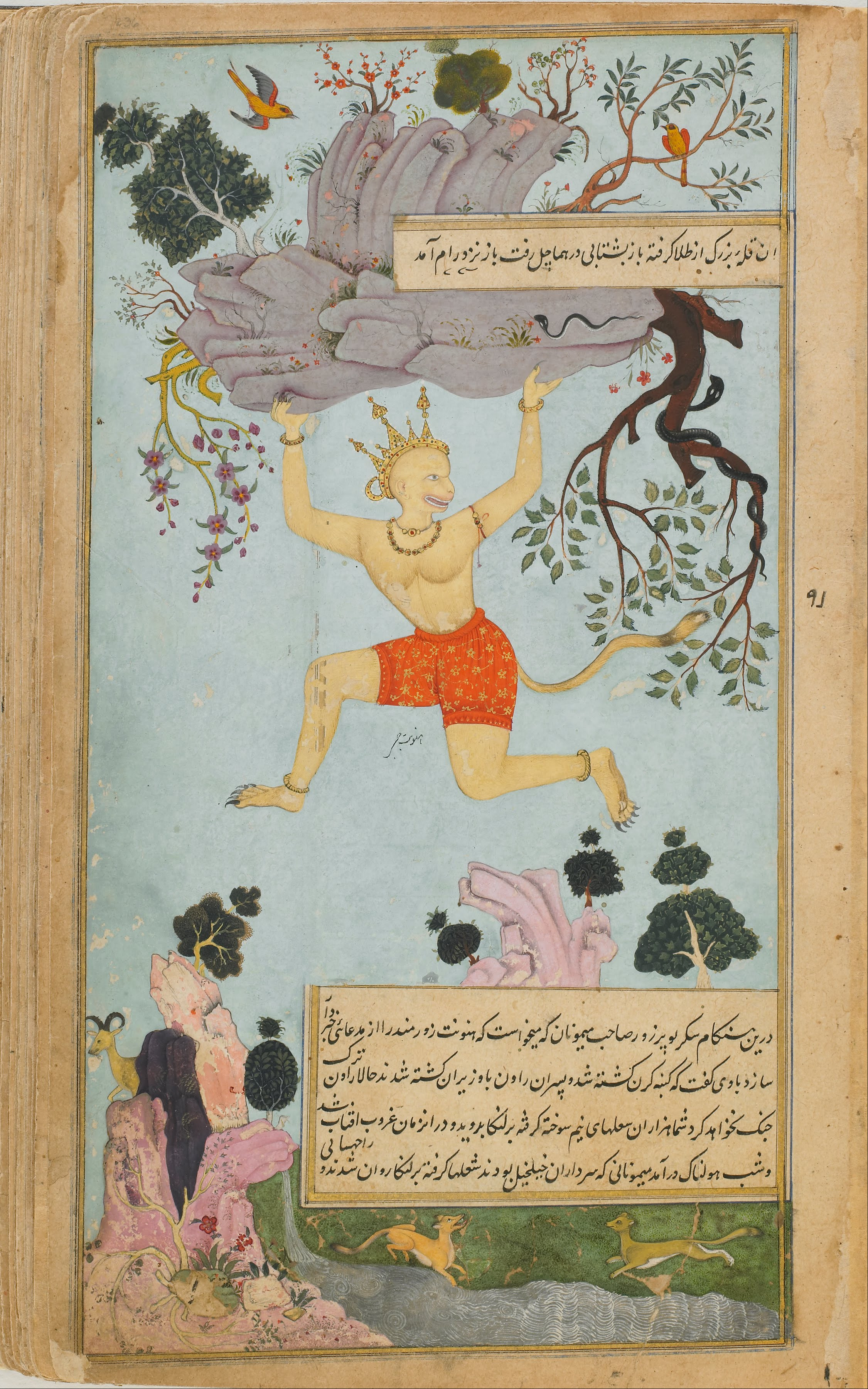

Again, the parallels are amazing. Sun Wukong’s chaotic attack on the Jade Emperor’s celestial city bears a marked resemblance to Hanuman’s airborne assault on Ravana’s city of Lanka. Like Hanuman, Sun Wukong could leap across oceans. The wind god, Vayu, fathered Hanuman, whereas the wind impregnated the egg from which Sun Wukong sprang.

Flying mountains play a part in the Ramayana as much as in Chinese Buddhist tradition. In the Ramayana, Hanuman flies to India to fetch Sanjivani herbs to cure the wounded Rama and Lakshman. Confused, he brings the entire Dunagiri mountain. According to tradition, five pieces of the mountain fell to earth, at Kachchativu, Thalladi, Ritigala, Dolukanda and Rumassala.

As evidence of Chinese folklore lineages emerged, such scholars as Hera Walker, have modified the Ramayana-origin theory. They think that while indigenous folklore did play a part in its creation, Hanuman provided the initial impetus. Walker thought that the maritime Silk Route trade, combined with the need to stay over due to the monsoon, played a major part in disseminating Indian culture eastwards. This helped spread the Ramayana mythology throughout South East Asia, and take it to China. The southern Chinese port of Quangzhou, the main Silk Route entrepot, played a vital part in the development of Sun Wukong from the legend of Hanuman.

Jatakas

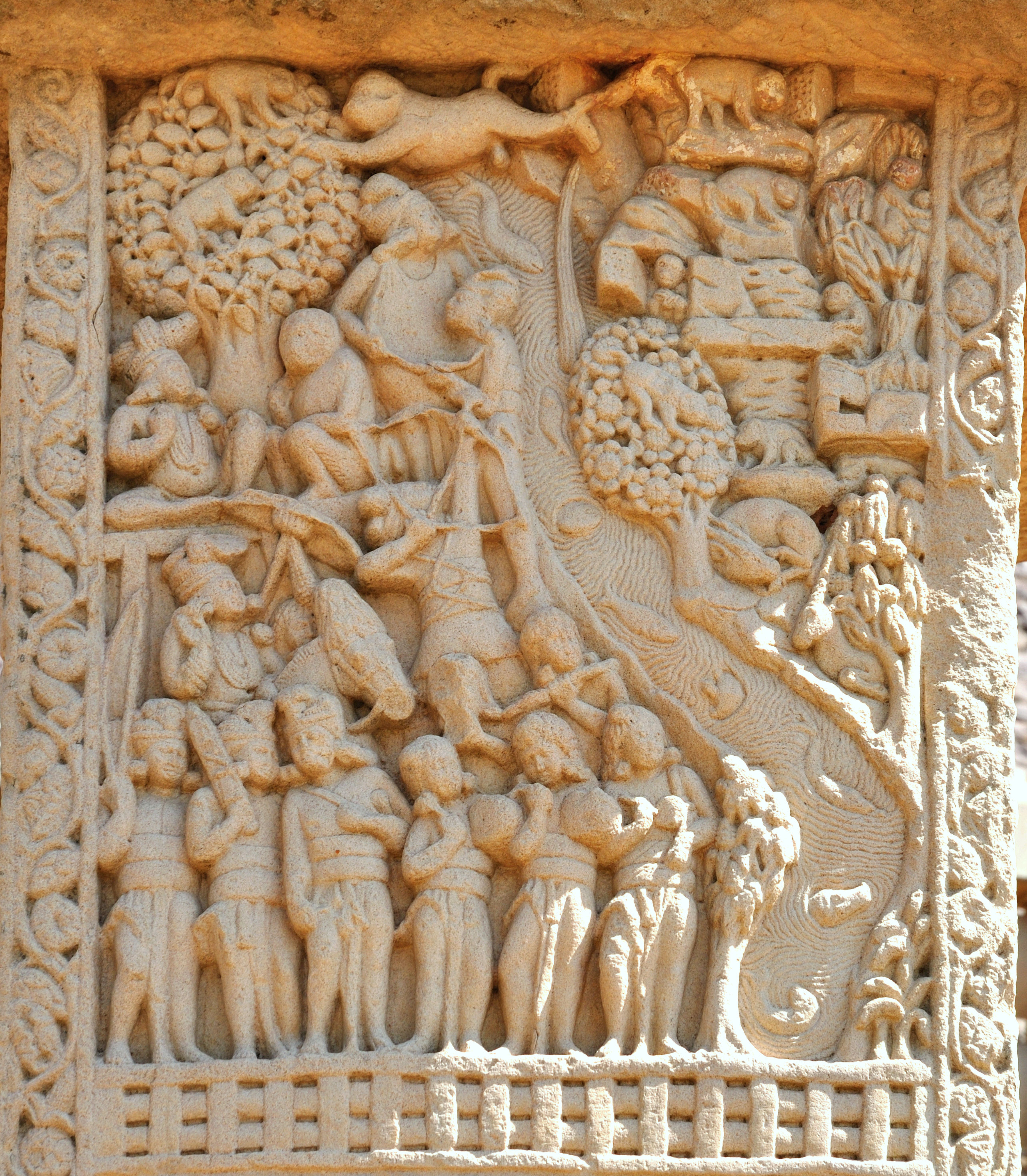

There is also a third possibility: that the Monkey King legend originated from the Buddhist tradition, but became enwrapped with Hindu myths and Chinese folklore. Stories featuring monkeys abound in the Buddhist Jatakas. Two of the Jatakas, the Tayodhamma Jataka and Mahakapi Jataka, have Monkey Kings. In the latter, the Monkey King has 80,000 followers, whereas Sun Wukong had 84,000.

The Orientalist scholar Richard Gombrich thinks that the Ramayana of Valmiki, upon which Buddhists looked down, may have led to a Buddhist counter-version in the Dasaratha Jataka. However, both these stories may have originated in the same folklore. Neither Xuanzang nor his predecessor Faxian, who visited Sri Lanka two centuries before, mention the story of the Ramayana, which only began to enter Buddhist texts after the fifth century.

Interestingly, the Buddhist tradition presents Ravana, the villain of the Ramayana—who never appears in the Dasaratha Jataka—in a positive light. The authorship of the Ayurvedic treatise Kumara Tantra is attributed to him. According to the Mahayana Lankavatara Sutra (a text mentioned by Xuanzang in Great Tang Records on the Western Regions) the Buddha went to the top of a mountain in Lanka (probably Adam’s Peak/Sri Pada) to discourse for the benefit of Ravana, a Rakshasa king who had plenty of good deeds under his belt.

In these circumstances, Chinese storytellers may have reconciled the Buddhist and Hindu traditions by conflating Ravana with the Jade Emperor, and Hanuman with the Monkey King.

The fabled hero of Journey to the West, and the tale of his personal odyssey from violence to harmony, represented the coalescence of several cultural and religious strands, and stands as a symbol of the peaceful engagement of different peoples in the ancient world.

Cover Image : Painting in the Summer Palace, Beijing, depicting the heroes of Journey to the West, Left to Right: Sun Wukong, Tang Sanzang riding his dragon/horse, Pigsy and Sandy. Image courtesy Wikipedia