A 130-km protrusion of land on Sri Lanka’s north-western coast has received a fair amount of local and international press in the past few months. Mannar Island, connected to the mainland by a causeway, has been identified as a rich source of the mineral ilmenite, which the Perth-based Australian company, Titanium Sands Ltd., hopes to mine. Mannar Island also happens to be pristine land within the Central Asian Flyway, making it a popular pitstop for migratory birds and bird watchers alike. It is also home to a unique ecosystem that environmentalists fear would be destroyed if mining permits are granted.

A Threatened Flyway

The Central Asian Flyway is a flightpath or migration route used by a large number of birds migrating south to breed during the northern hemisphere’s winter. It covers a vast distance stretching all the way from Northern Asia to Sri Lanka, which is the final stop on the flyway.

Uditha Hettige, Director of Bird and Wildlife Team Pvt. Ltd., told Roar media that migratory birds are drawn by the country’s steady, tropical climate, and that Mannar Island is one of the chief crossovers into Sri Lanka. The island is an entry point, a wintering site as well as an exit point for these birds, who flock in here in millions. This route is of great importance especially for birds belonging to the Passeriformes order, which encompasses more than half of all bird species, including songbirds and perching birds. This is because these particular birds — not known to be great flyers — rely on the Adam’s Bridge Islands, at the end of which is Mannar Island, to reach their destination. The Adam’s Bridge Islands provide an emergency landing area in bad weather, and after some island hopping, the first substantial landmass these birds reach — regardless of whether or not they are good fliers — is Mannar Island. After the arduous journey of over 1,000 kilometres, the first drink of fresh water they receive is on Mannar Island.

Mannar Island attracts not only Passeriformes, but also waders. Hettige notes that as many as half a million ducks have been counted here, and during the 2011 water bird census conducted in conjunction with Wetlands International South Asia on the nearby Vidataltivu reserve, at least 1.2 million birds were counted feeding.

A Dynamic Ecosystem

All this is sustained by the unique ecosystem of Mannar Island, which is home to salt and brackish water, and mud and sand flats that attract wading birds.

According to Hettige, the sea is shallow for the most part, but during one part of the year, the low tide creates more sandy enclosures, as well as shallow inland bodies during high tide, an important feeding ground for birds and part of Mannar Island’s unique ecology. The combination of saltwater and rainwater creates brackish water, important for ducks and waders, and the thousands of migratory birds that feed here.

Although Mannar Island is classified by Sri Lanka as an ‘arid zone’, Hettige says this assessment is misleading, because it promotes the idea of a barren wasteland. The island’s ecosystem, he explains, both marine and terrestrial, is diverse and unique. According to an IUCN report, it is home to “patches of scrubland and extensive Palmyra woodlands, as well as coconut plantations . . . also found around the island are tidal flats and small patches of sea marshes . . . as well as sand dunes near the tip of the island.” One of Sri Lanka’s oldest and largest individual baobab trees is also on Mannar Island (an estimated 700 years old!).

Mannar Island also supports several threatened and endemic species. The IUCN report estimates that “more than 30% of the birds recorded in Sri Lanka (more than 150 species) have been recorded on the island.” This includes some incredibly rare species of birds such as the spot-billed duck (Anas poecilorhyncha), black drongo (Dicrurus macrocercus), long-tailed shrike (Lanius schach), Eurasian collared-dove (Streptopelia decaocto), grey francolin (Francolinus pondicerianus), black kite (Milvus migrans), crab-plover (Dromas ardeola), great black-headed gull (Larus ichthyaetus), Eurasian wigeon (Anas penelope) and the black-tailed godwit (Limosa limosa).

The island’s marine ecosystem, meanwhile, supports seagrass meadows, and is also home to endangered dugongs and marine turtles. The report also notes that the Indo-Pacific finless porpoise, a globally vulnerable species, was recently discovered off the tip of Mannar island.

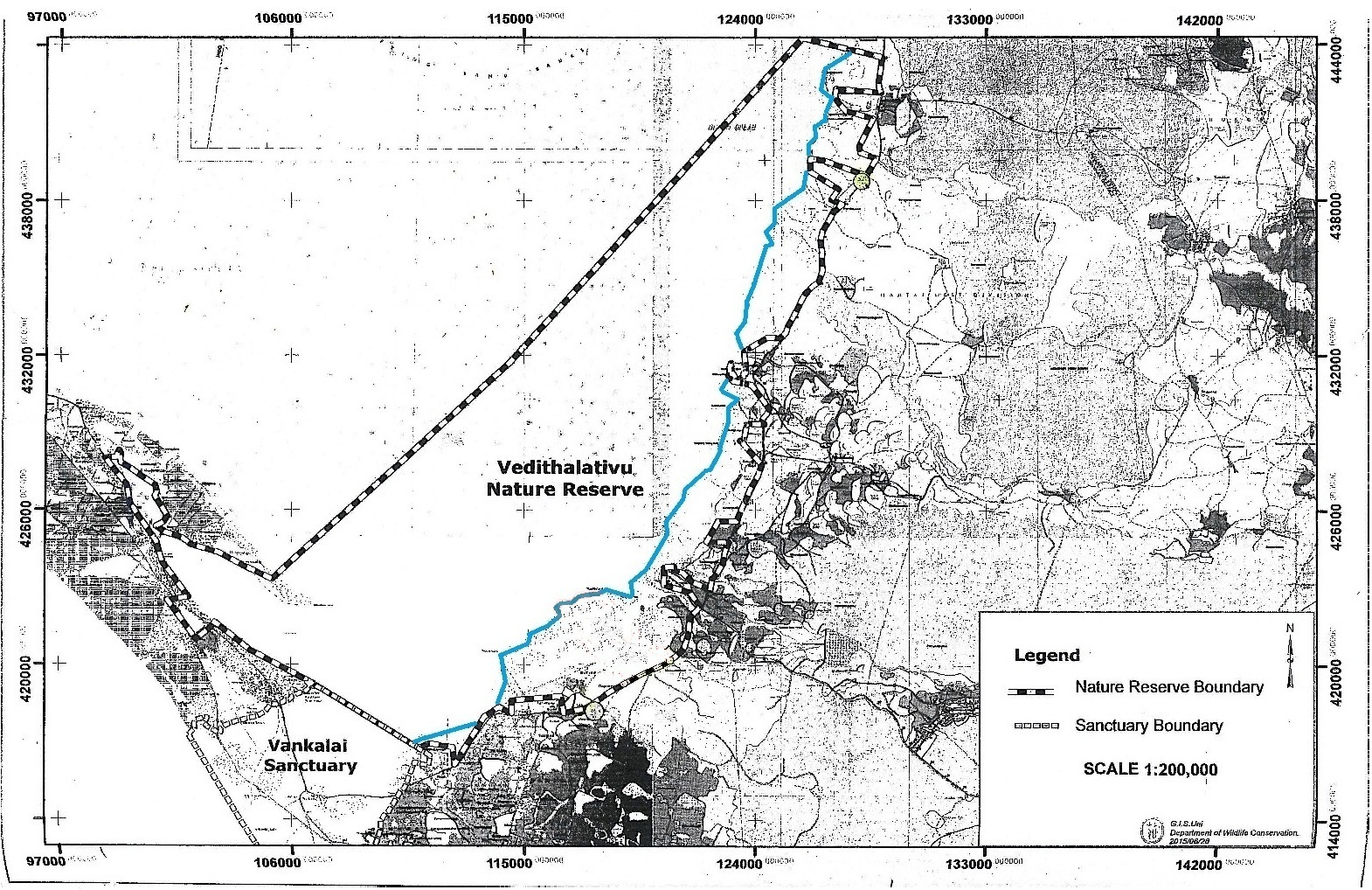

What protected Mannar Island from destructive human encroachment was, ironically, the war, which isolated the island and allowed for its biodiversity to thrive. Off Mannar Island is the Vankalai Sanctuary, a RAMSAR wetland. Stretching from this to the Vidataltivu Lagoon is one of Sri Lanka’s best preserved mangrove forests, leading out straight to the sea, supporting a legion of marine life such as shrimps, prawns, and the infamous Jaffna crabs. The island and the waters surrounding it are a biodiversity hotspot, which has not been included in the FAQ Titanium Sands Ltd. supplied when media coverage brought to notice the proposed plans to mine the island for heavy mineral sands. An environmental impact assessment (EIA) is yet to be conducted — the plans to mine Mannar Island have, therefore, yet to account for the destruction of such a unique habitat, one that supports over 30% of the country’s avi-fauna.

Veteran environmentalist and attorney-at-law Jagath Gunawardana told Roar that mining could pose a potential threat to the island, and that mining below the water table may introduce salt water that would contaminate fresh water resources. He added that a thorough environmental and geological assessment will be required to determine the effects of mining on the narrow, sandy Mannar Island.

The Confusing Gist

Titanium Sands Ltd. (TSL) is a Perth-based mining company, listed with the Australian Stock Exchange (ASX:TSL), formerly known as Windimurra Vanadium Ltd. TSL acquired two Mauritius-based companies, Srinel Holdings Pvt. Ltd and Bright Angel Ltd., which in turn control a number of mining exploration licences in Sri Lanka via subsidiary companies based in Sri Lanka. Srinel Holdings Ltd. was acquired by TSL on 29 January 2016, while reports were published in March 2020 of TSL’s acquisition of Bright Angel Ltd.

An update provided by Windimurra Vanadium Ltd to the Australian Stock Exchange shows its interest in acquiring Srinel Holdings Ltd., as early as 2014. The document includes a full drilling report on Mannar Island written by GeoActiv (Pty) Ltd, which was contracted to manage and conduct the work on behalf of Srinel.

Following that, according to investigations by News First, Srinel Holdings Ltd. appears to have acquired at least three subsidiary companies, namely Kilsythe Exploration Pvt Ltd., Hammersmith Ceylon Pvt Ltd., and Sanur Minerals Pvt Ltd. Bright Angel Ltd. meanwhile, acquired Sri Lanka-based Orion Minerals Pvt Ltd., and Supreme Solution Pvt Ltd. All five subsidiary companies were registered in 2015, and they are, through a series of hand-changing, linked to three individuals named Kobiraman Balakrishnan, Priyantha Abeywardena, and Robert Nelson.

Anura Walpola, Chairperson of the Geological Survey and Mines Bureau (GSMB), informed Roar Media that investigations into the issue of the licences are to begin shortly and that a team has been appointed for this purpose. He said that TSL has managed to gain nine mining licences through the subsidiary companies and that the GSMB will be able to provide further clarity on the subject soon.

Back in 2019, meanwhile, TSL reported that in addition to the 52 million tonnes of identified heavy metals, they had identified an estimated 32 million tonnes as found on a property adjacent to the land initially earmarked for mining. By May 2020, however, the total figure was more than tripled to 264.93 million tonnes. In the words of James Searle, Managing Director of TSL, “This massive upgrade in resources for the Mannar Island Project makes a very long-life large-tonnage dredge mining operation a serious consideration.” It is, as he has also noted, a “robustly economic project.”

And just how serious does TSL expect the project to be? One serious enough to span more than 20 years, at the very least, according to reports — with the scope of the project changing from “modest” to “large” within the space of a year. TSL has not discounted the possibility of finding heavy minerals under the water table; for that matter, the heavy mineral sands are said to be contained in near-continuous bodies from two to three metres above, to at least 10 metres below the water table. TSL expects good recovery of at least 90% of the primary product, which is, namely, high-quality ilmenite.

As Searle explains, this will primarily be used in the pigment industry for plastics and paints, but TSL will also cater to other specialised markets for rutile, zircon, and the recently identified garnets. The industry he speaks of is, as their investor presentation highlights, a US 340-billion dollar industry, with the global paints and coatings market forecast to reach USD 204.83 billion by 2023 and the ceramic tiles market expected to reach USD 145 billion by 2022. In return for mining in Sri Lanka, the country will only receive 4-5% of the royalties.

Concerns And Discrepancies

According to TSL, the post-mining benefits of the project “may include employment opportunities as well as fully rehabilitated land with the potential for income-producing crops to be developed for the benefit of the local community (such as cashew or coconut crops by way of example)” [emphasis added]. There is no mention if this will potentially affect and alter the unique and fragile ecosystem of Mannar Island, or what consequences it will have for migratory birds and the island’s fauna. So far, TSL’s focus, if and when the environmental impact of the project is mentioned, is on Mannar’s coastal fisheries and the Vankalai Nature Sanctuary. “The Company is firmly of the view that both are of a sufficient distance from the proposed Project [sic] area to not be at risk,” reads the company’s media statement. There is no indication of how the landscape of Mannar Island itself stands to be affected.

What is interesting to note, however, is the apparent discrepancy between the media statement released by TSL and their investor presentation dated a few months before the media release. In the media statement, the company claims that “preliminary concepts for the project based on an area of the identified heavy mineral resources [is] 1km to 2km wide and up to 8km long [,] located between 1 and 3km from the nearest coast of Mannar Island.” In its investor presentation, meanwhile, TSL was happy to note that “The Titanium Sands project encompasses almost 204km2 / 93% (approx.) of Mannar Island in Sri Lanka’s North West.” This presentation was made before the company realised it was sitting on approximately 264.93 million tonnes of heavy minerals.

While this may be termed a “developing story”, with further investigations expected to provide a clearer picture of the confusing tangle that is the Mannar Island mining project and where it stands legally, what should be noted is the apparent evasion of the possible impact the project will have on the environment and wildlife of the island itself. Mannar Island is, indeed, a rich resource — but perhaps not in the same sense that Titanium Sands sees it.