Tucked away neatly in the heart of Sri Lanka’s official capital city, Kotte, is a structure made of kabok or laterite stones. This structure predates all other buildings and houses in the area and is better known as the Ramparts of the Ancient Kingdom of Kotte. As if to exemplify the neglect and decay of the long lost kingdom, a pair of underwear, presumably left by one of the residents in the area, is casually laid out to dry on one of the stones of the rampart. To find out more about what happened to the remnants of the ancient kingdom of Kotte, it is necessary to use the above mentioned spectacle as a metaphor for the gross insensitivity and indifference towards monuments of the past.

Stepping back in time

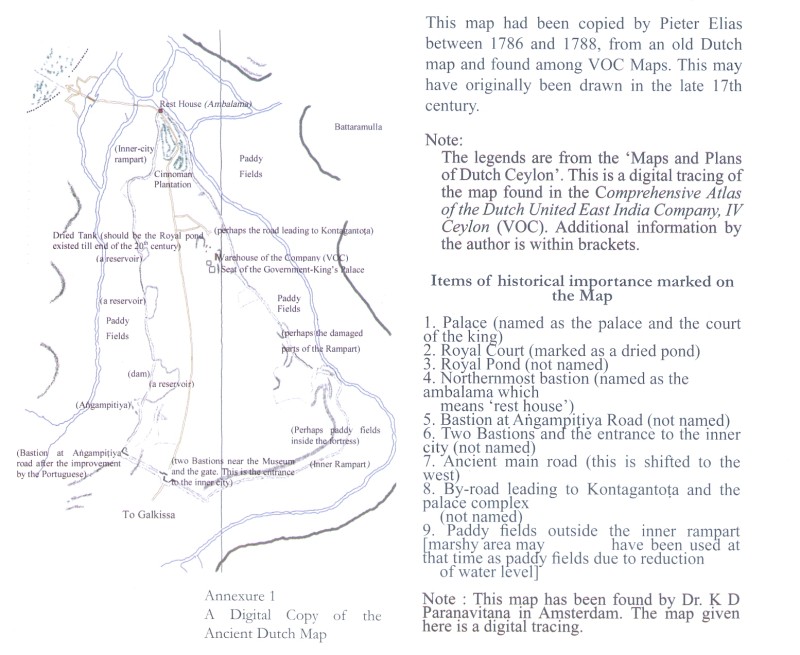

Ancient Sri Lanka had four long-term capitals, one of which was Kotte. Professor Senerat Paranavitana* who was Archeological Commissioner in 1940 noted that Kotte was rebuilt and fortified during the reign of Vikramabahu III (A.D. 1357 – 1374) by the minister Alakesvara and was made the seat of government during Parakramabahu VI’s reign (A.D. 1412 – 1467). After Parakramabahu VI’s death, with the decline of the empire and the Portuguese takeover that followed, the Portuguese relocated the seat of power to Colombo and abandoned the city of Kotte for strategic reasons. What had not been destroyed during warfare had been taken over by jungle or transported for construction of buildings in Colombo by the Portuguese and subsequently, the Dutch. During the Dutch period, Kotte was reoccupied and Professor Paranavitana speculates that the new house owners, too, would have “utilised the material lying abundantly at hand in putting up their homesteads.”

Kotte today

The Kotte of today, apart from a few scattered relics, neglected ramparts and road names, doesn’t proudly boast of such a past because the past has not been preserved. As Professor Paranavitana notes, “the consciousness of the people was not sufficiently alive to the importance of preserving a heritage… and the destruction of such antiquities as were till then to be seen on private lands of Kotte, went on unchecked, so that today, the visitor who sees its suburban drabness is not reminded, by any conspicuous relic of the past, that he is at a spot which was the centre of the political and cultural life of the island during a period of its history not lacking in achievement.”

As the official capital city of Sri Lanka, Kotte is now home to the Sri Lanka Parliament, the Diyawanna Oya, high property prices and a Kotte museum. However, as Nihal Perera PhD, notes, almost all other museums in Sri Lanka are better maintained than the Kotte museum.

At this museum, we posed the question of what happened to Kotte to the gentleman in charge. He explained that apart from being built from kabok, which is not durable, the shifting of the capital city back to Kotte in 1982, during J.R.Jayawardena’s presidency, ensured the final destruction of all that remained of the ancient kingdom of Kotte.

“Despite evoking the glory of Kotte, the physical and archaeological remains of the Kotte Kingdom largely lie in a state of neglect and disrepair,” Dr. Perera notes.

“[Even] two decades after the move [of the capital to Kotte], there is no restoration activity and the physical remains from the Kotte period, including stupas, the wall, and the tunnels, are allowed to be naturally destroyed.”

Dr. Perera contends that Kotte, although the capital, doesn’t in any way stand out from the rest of Colombo. “For most users, the area is a continuation of Colombo made up of highly congested roads,” he said.

A curious juxtaposition of the ancient and the modern: a trishaw parked next to the remains of the ramparts.

A curious juxtaposition of the ancient and the modern: a trishaw parked next to the remains of the ramparts.

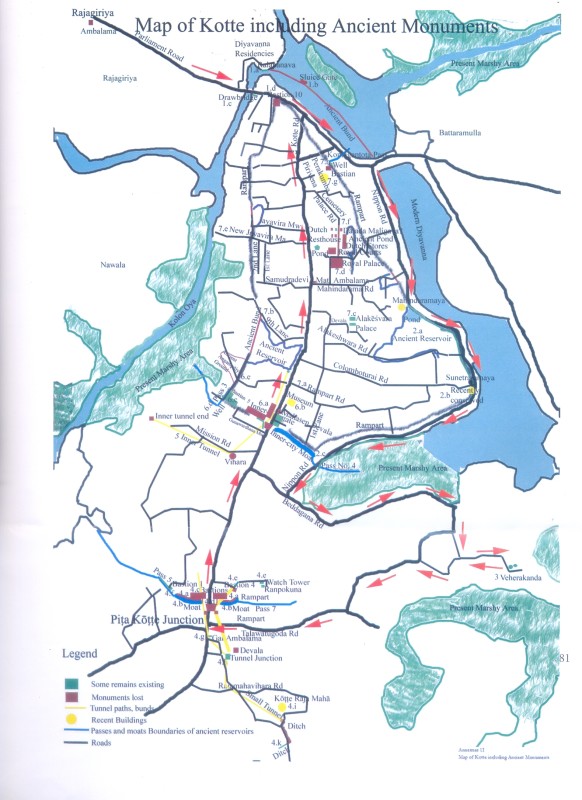

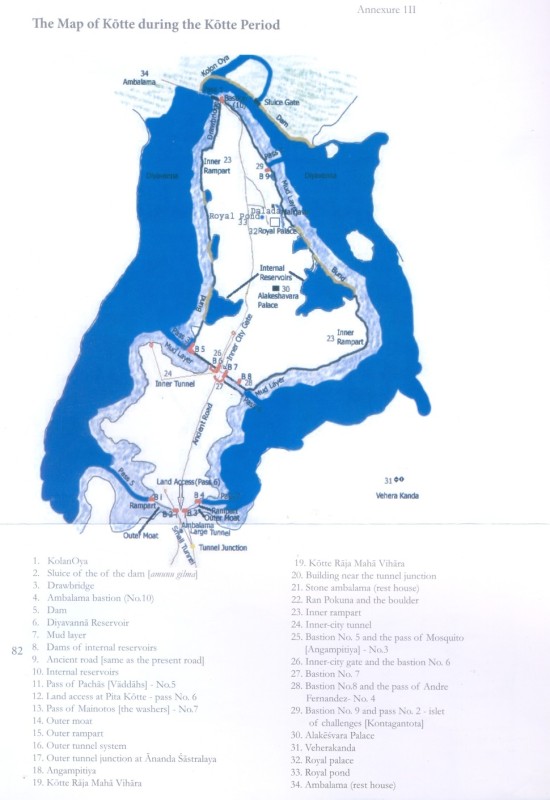

Visitors in search of hints of a more glorious past may find road names such as Maligawa Road, Ferry Road (now Mahindarama Road), Mission Road and Rampart Road deceptive relics of the past. There is no Maligawa down Maligawa Road, or a Temple of the Tooth Relic. The ramparts are scattered around and built over. Nothing remains of the ferry that the name Ferry Road seems to suggest, but there are hints of what was once the inner moat, which now resembles a drain more than anything. Hilary Wirasinha, resident of Kotte and amateur historian, notes that right in front of the moat is the construction of a condominium, permission for which was obtained from the Archaeological Department, despite the need to preserve the inner moat. In the school down Mission Road there was even an entrance to a tunnel that was said to have connected Etul Kotte to Pita Kotte. The tunnel is supposed to have led to Ananda Sastrala. There were two ambalamas, one of which still stands and was reconstructed on the same spot and transformed into a bus stand and two stupas at Veherakanda, which are also referred to as kotaveheras. Apart from a few hints here and there, however, there is little evidence that Kotte was once a Kingdom and the centre of political life in Sri Lanka.

To make matters worse, the museum curator also noted that excavation is nigh impossible due to the houses and structures built in the area. What we have instead of a heritage site of the Kingdom of Kotte, is a suburban sprawl known for its narrow roads and traffic jams made worse by its proximity to the parliament.

Speaking to the Director General of Archaeology, Dr. Senerath Dissanayake, it was understood that the department itself is underfunded, making conservation difficult. “We have a limited amount of money to carry out projects. In addition, most of the monuments are on privately owned lands,” he said. When asked about the building permit given for the construction of the condominium in front of the inner moat, he said that as per regulations, there is a 10ft buffer zone between the construction site and the moat. “We are working with limited resources and funds. We don’t have enough watchers, either,” he said.

There are, of course, boards in numerous places put up by the Archaeological Department that hint at a richer, more glorious history. Yet, it should be noted that if even the Archaeological Department lacks the funding for the required conservation, there is little hope for the preservation of what was once Sri Lanka’s ancient capital.

*From his essay “Baddegana at Kotte”

Scanned maps courtesy Kotte: The Fortress by Prasad Fonseka

You will find boards like this, put up by the Archaeological Department, all around Kotte but you will be hard pressed to find actual relics of the ancient Kingdom of Kotte.

You will find boards like this, put up by the Archaeological Department, all around Kotte but you will be hard pressed to find actual relics of the ancient Kingdom of Kotte.