What do the Dambulla Rock Temple, the Pyramids of Giza, and Australia’s Great Barrier Reef have in common?

If someone were to throw the question at you, you’d probably brush it off as the beginning of a bad joke. “Is that a trick question?” you’d ask, and then wait for the punch line ‒ because who would imagine that anything on this humble little island of ours could commensurate with monumental wonders like the Giza Pyramids? Well, it turns out that they do have something in common ‒ an honoured place on the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites.

For a small island encompassing a mere 62,710 square kilometers of terrain, Sri Lanka has an almost absurdly large number of manmade and natural marvels, ranging from colonial strongholds and ancient cities to rainforests and cave monasteries. Eight of these sites are considered to be of such significance to humanity that they are now established as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, rubbing shoulders with wonders like the Acropolis of Athens and China’s Great Wall and marked to be protected and preserved for future generations.

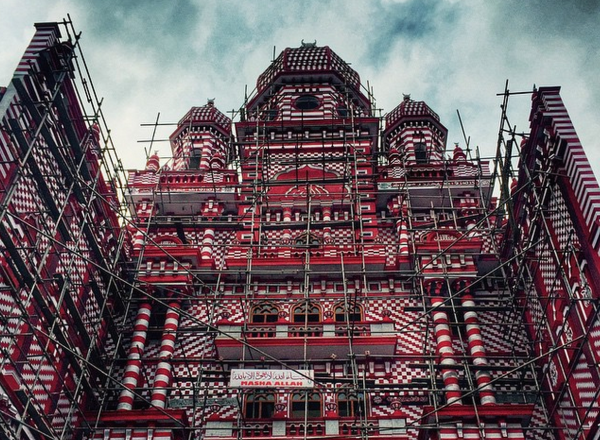

Having World Heritage Sites in the country isn’t simply a matter of letting them stand and reel in busloads of tourists. Many of these monuments have been exposed to the elements for hundreds of years and require meticulous restoration and care in order to be brought back to and preserved in their original states. The newly restored and renovated Abhayagiri Stupa, for instance, was unveiled in July last year after fifteen years of painstaking restoration work in a UNESCO-sponsored conservation programme by the Central Cultural Fund of Sri Lanka. The same project also focused on other monuments in Sri Lanka’s famous cultural triangle, like the Jetavarama Stupa.

Abhayagiri Stupa, the second largest stupa in the world, undergoing restorative work by the Central Cultural Fund as a UNESCO project.Image courtesy: wikimedia.org

However, in spite of their protected status, it seems like Lanka’s world heritage sites are not always as well-cared for as they should be. For instance, just about a month ago, it was reported that UNESCO Director-General Irina Bokova, during her recent visit to Sri Lanka, had warned local authorities that the Dambulla Rock Temple faces the risk of being divested of its status as a World Heritage Site. Despite Sri Lanka being legally bound by an international treaty (the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage) to protect and conserve the historic cave monastery, poor maintenance, and unsuitable new constructions threaten to diminish its heritage value.

Even the Sigiriya rock fortress, which was given World Heritage Site status in 1982, is frequently reported to be in danger of suffering damage of varying degrees due to easily preventable factors such as a lack of sufficient crowd control measures and blatant carelessness.

Being home to World Heritage Sites comes with responsibilities, and these responsibilities – namely, ensuring that effective and active measures are taken for the protection, conservation, and presentation of each site – fall on the state party to the aforementioned convention. This, as Bokova is said to have pointed out, happens to be the government of the country in question, which means it is up to the Sri Lankan Government to preserve and maintain the historical value of these priceless legacies of our past.

The idea of World Heritage is special for many reasons, but primarily because it transcends mundane concepts like state boundaries and nationalities into universality. Theoretically, it does not matter which country or state it is in; a World Heritage Site belongs to the world, and that applies to the eight amazing ones right here on our very own island:

The Ancient City Of Sigiriya (1982)

Often referred to as the eighth world wonder, the Sigiriya rock fortress is one of the most iconic monuments of Sri Lanka. Image courtesy: bapasanewmockingbird.webdesigns.net

History plainly depicts King Kashyapa as a cruel, black-hearted villain who stole the throne from his brother and gruesomely murdered his father by walling him up alive, but in his paranoia and greed, this particular ruler achieved one of the most incredible architectural feats in history – the impregnable ‘fortress in the sky’, Sigiriya.

It is easy to see why this massive monolith was honoured with a place on the List of World Heritage Sites. Rising a staggering 660 feet into the sky, the rock fortress along with the ruinous city at its feet serves as an enduring reminder of the ingenuity and skill of the people of Sri Lanka’s bygone eras. Sigiriya and its surroundings are full of wonders; everything from the Mirror Wall and the famous frescoes to the magnificent water gardens and colossal lion’s paws engraved into the bedrock are testaments to its historical and cultural significance.

However, in spite of its protected status, the safety of this iconic monolith appears dubious. For instance, news reports on the Sigiriya frescoes being damaged are not uncommon. These famous frescoes, said to depict the beauties of long ago Lanka, have so far withstood the passing of centuries, but it seems like a lack of crowd control and occasional carelessness will be their undoing. It would be a heartbreaking thing indeed if something as monumental as the Sigiriya fortress, which has weathered storms for hundreds of years, were to suffer harm due to something as mundane as an insufficient number of security guards.

The Ancient City Of Anuradhapura (1982)

Built by kings; the picturesque ruins of Anuradhapura’s Lankarama stupa. Image credit: Matthew Williams-Ellis

The home to wonders such as the Sri Maha Bodhi, Ruwanwelisaya, and the great Jetavarama, the city of Anuradhapura remains one of the country’s most visited locations. Here, amongst the sprawling ruins, there once flourished the heart of Sri Lanka’s ancient civilizations. The city has seen much – the rise and fall of more than a hundred kings and queens, the advent of Lanka’s Buddhism, wars and intrigues, peace and prosperity, the construction of great monastic edifices and picturesque pools; and even now, thousands of years later, vestiges of a glorious past remain. The Jetavarama Stupa, for instance, which was once rivaled only by the Giza Pyramids in height, remains the world’s largest stupa, while the sacred Sri Maha Bodhi tree is the oldest known human-planted tree on Earth.

Anuradhapura was the first capital city of Sri Lanka, and it was established in the 4th Century BC by King Pandukhabaya. For more than a millennium, it thrived as a religious and political centre before being ravaged by invaders, then abandoned and replaced as capital by Polonnaruwa. The city lay hidden within the dense jungle for many years before being rediscovered and made accessible again. Now filled with striking ruins of dagabas, palaces, temples, and ponds, the city bears testimony to the former glory of the Kingdom of Anuradhapura. Considered a sacred place by Buddhists all over the world, its significance was globally recognised when it was awarded a place on UNESCO’s list of World Heritage Sites in 1982.

The Ancient City Of Polonnaruwa (1982)

The ruins of the ancient Polonnaruwa vatadage, a circular stone shrine believed to have been built to house the tooth relic of the Buddha. Image courtesy: futuresrilanka.lk

If you ever feel like communing with our country’s history, a visit to Polonnaruwa would be a good idea.

The second city to be established as capital in Sri Lanka, Polonnaruwa’s historical prominence is surpassed only by that of Anuradhapura. However, unlike Anuradhapura, which was a thriving kingdom for centuries, Polonnaruwa’s time in history’s spotlight was relatively brief, lasting only for about three hundred years before the city was abandoned to the jungle following a Chola invasion. Still, under the patronage of great kings like Parakramabahu I and his nephew Nissanka Malla (who admittedly bankrupted the country, but still bestowed it with some pretty impressive legacies), the city rose to magnificent heights during its golden age, endowed with complex irrigation systems, sweeping reservoirs like the Parakrama Samudra, and architectural marvels like the famed garden city and the Gal Viharaya. The city is also home to many Brahmanic monuments built by the invading Cholas who seized power over the island for some time.

The Sinharaja Forest Reserve (1988)

Almost haunting in appearance, this forest pool is one of many that can be found in the Sinharaja’s verdant depths. Image courtesy slncu.lk

The jewel in the crown of Sri Lanka’s resplendent natural heritage, the Sinharaja Forest Reserve is the last viable area of primary tropical rainforest in the country to remain practically undisturbed.

The fact that the rainforest has been designated both an MAB Biosphere Reserve and World Heritage Site by UNESCO is a testament to its incredible significance, both locally and internationally. In the 1970s, all timber exploitation in the forest was banned, and the forest’s flora and fauna was given full protection when 2,500 hectares of the forest was made into an IUCN-IBP Strict Reserve.

The Sinharaja forest, whose name literally translates as “lion king” abounds with lush greenery, shadowy hollows, forest pools, and running streams, and is an incredible biodiversity hotspot. Thriving in its dense mysterious depths is an amazing wealth of wildlife and vegetation; climbing lianas and wild orchids, stunning bird life and rare snakes, captivating species of insects, fish, and amphibians, and other fascinating creatures like the shy pangolins and the elusive leopard. Many of the species there are endemic to the island, and it is partly this high rate of endemism that makes the region such an invaluable asset to the country. For instance, out of the twenty endemic species of birds in Sri Lanka, eighteen of them can be found in the Sinharaja Forest, while 60% of the forest’s trees are said to be endemic.

Even now, after all the years of exploration and study it has been subjected to, the forest still seems to have more secrets to divulge. Just recently, a new species of snake, aptly named the Sinharaja tree snake, was reported to have been discovered in the forest canopy.

The Old Town Of Galle And Its Fortifications (1988)

The rolling grassy plains of the Galle Fortress. Image courtesy: uncharted101.com

Galle is one of those places which come to mind with a big “beach holiday destination” label tacked to it, but beaches aren’t the only thing this Southern town is famous for. With a World Heritage Site tag to its name, it is no doubt a place of historical significance.

Galle is home to the famous Galle Fort (or the Galle Ramparts as it is also known), the Portuguese founded fortifications which reached the pinnacle of their development in the 18th century under the Dutch rule. Its days as a glorious fortified town are quite gone, but with its picturesque stone structures, soaring lighthouse, cobbled streets, clock tower, and quaint colonial-style houses, it still exudes the atmosphere of those long-ago days when Lanka was shackled under colonial rule.

According to UNESCO, the Galle Fort, which displays an extraordinary interaction between European architectural styles and South Asian traditions, remains an unsurpassed example of a fortified city built by Europeans in South and South-East Asia. In spite of the constant battering of rain, wind, and sea, restorative work has kept this site largely unspoiled. Even during the 2004 tsunami, the Galle Fort, built to withstand cannon fire back in its heyday, suffered comparatively little damage, and has since been restored.

The Sacred City of Kandy (1988)

The resplendent interior of the Temple of the Tooth Relic. Image courtesy: flylankatravels.com

The third ancient capital city of Sri Lanka to be inscribed in UNESCO’s list of World Heritage Sites, Kandy served as the stronghold of the Sinhalese kings for nearly 300 years before the city and its last king Sri Wikrama Rajasinghe fell to the British forces in 1815.

Kandy’s outward veneer of lush green hills and rolling mountains soon vanishes as you travel into the thronging city, for there at its heart is one of the most venerated sites of the Buddhist world ‒ the Dalada Maligawa, or the Temple of the Tooth, which houses the sacred tooth relic of the Buddha. Spread out around it are other edifices of remarkable architectural, cultural and archeological significance, like the ruins of the ancient royal palace built by King Vimaladarmasuriya I and the famed audience hall of the Kandyan kings, where the great monarchs once held court and decided on matters of state.

Also known as Senkadagalapura or Mahanuwara (the English name Kandy was given by the colonials), the city of Kandy was the last capital of the Sinhala Kings, but unlike its predecessors Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa, it captures a rather different ethos, a melding of the unique Kandyan styles of architecture with vestiges of colonial rule.

The Golden Temple Of Dambulla (1991)

Statues of the Buddha in the Cave of the Great Kings. The intricate murals covering the stone walls depict scenes from the Buddha’s life. Image courtesy: wikimedia.org

Steeped in history and legends, this 2,200 year old cave monastery provides a fascinating insight into our country’s resplendent past.

The Dambulla Rock Temple has been a Buddhist site of pilgrimage for hundreds of years, and could well be the largest and best-preserved cave temple complex in Sri Lanka. Comprising of five stone chambers saturated with colourful murals, intricately carved statues and ancient artifacts, the cave complex serves as a substantial link to Sri Lanka’s history, and continues to draw crowds of visitors year after year.

It was here, within these rocky walls, that King Valagamba is supposed to have sought refuge when he fled the Chola invaders in the 1st century BC. As history goes, when he finally regained the throne after fifteen years of exile, he gratefully converted the caves into a magnificent monastery. Many proceeding kings are recorded to have further embellished and developed the temple to its current splendour, so that it now boasts a hundred and fifty-seven statues and 2,100 square meters of elaborate Buddhist murals.

Considering the immense religious and cultural significance of this site, it is surprising that Dambulla’s Golden Temple seems to be facing the imminent danger of being struck off the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites. As we previously mentioned, poor maintenance and new constructions are reported to have perverted the heritage value of the cave monastery. We can only hope that the Government wakes up from its seemingly perpetual stupor and takes action to undo the damage done and ensure that the site remains unspoiled for the future generations.

The Central Highlands Of Sri Lanka (2010)

Where the wild sambhur roam. Image courtesy: wondersofnaturalsl.blogspot.com

Of the eight World Heritage Sites in the country, the Central Highlands of Sri Lanka is the most recently established one, having being conferred the honour only in 2010. Like the Sinharaja Forest Reserve, the area – which comprises the Horton Plains National Park, Knuckles Conservation Forest, and the Peak Wilderness Protected Area – falls under the category of Natural Heritage Sites, rubbing shoulders with global marvels like the Great Barrier Reef.

Anyone who has hiked through the misty cloud forests of Horton Plains or followed the secret mountain paths of the Knuckles Mountain Range would easily understand how these magical regions got their badge of honour. Up there in Sri Lanka’s pristine central highlands is a perfect treasure-trove of natural wonders – otherworldly vistas, Middle-Earth-like montane forests, and a wealth of unique endemic flora and fauna – which has the place marked as an incredible biodiversity hotspot. Many species found there, such as the western purple-faced langur, the Horton Plains slender loris, as well the Sri Lankan leopard, are considered endangered species, while many others are classified as endemic, some to the country, and some even to the region.

Sadly, Sri Lanka’s Central Highlands are another case in point of a World Heritage Site which is facing serious threats. The Knuckles Mountain range, for instance, is notoriously prone to forest fires in the dry season. Just last month, hundreds of acres of forest suffered terrible devastation when fires broke out, leaving trails of destruction across the World Heritage Site and causing a significant loss of plant and animal life. Considering the high density of wildlife and vegetation that thrive in the area, it is likely that a large number of creatures and plants endemic to the area have been destroyed. The cause of the fire remains uncertain ‒ it could be natural or even acts of arson, but the question remains: could nothing have been done to minimise the destruction caused?

One tiny island with eight awe-inspiring Heritage Sites. It is something to be proud of indeed, but being home to a World Heritage Site means more than just holding a shiny label to be flaunted on tourist websites and travel brochures; it is a badge of honour pinned in place by a contractual and moral obligation of the country to do the best it can in its power to protect and preserve the site. There is no doubt that the Central Cultural Fund and other relevant organisations have done extraordinary jobs restoring and repairing countless invaluable monuments around the island, but, as evident from the recent warning from the UNESCO Director-General, more needs to be done before we can feel completely secure about our heritage. Our cultural and natural heritages are irreplaceable; it would be a sorry state of affairs indeed if Sri Lanka’s future generations would not be able to witness them in their existing magnificence .

Featured image courtesy: futuresrilanka.lk