The importance of cybersecurity has grown at an exponential rate during the past few years. In a 2019 report, Accenture estimated cybersecurity costs to reach as much as USD 5.9 trillion within the next five years. It’s a global issue that should not be left unattended, particularly given the current circumstances. Work-from-home schedules and pandemic responses by governments around the world have propelled the adoption of digital tools. This is true even in Sri Lanka, with its initiatives like the ‘Stay Safe’ solution.

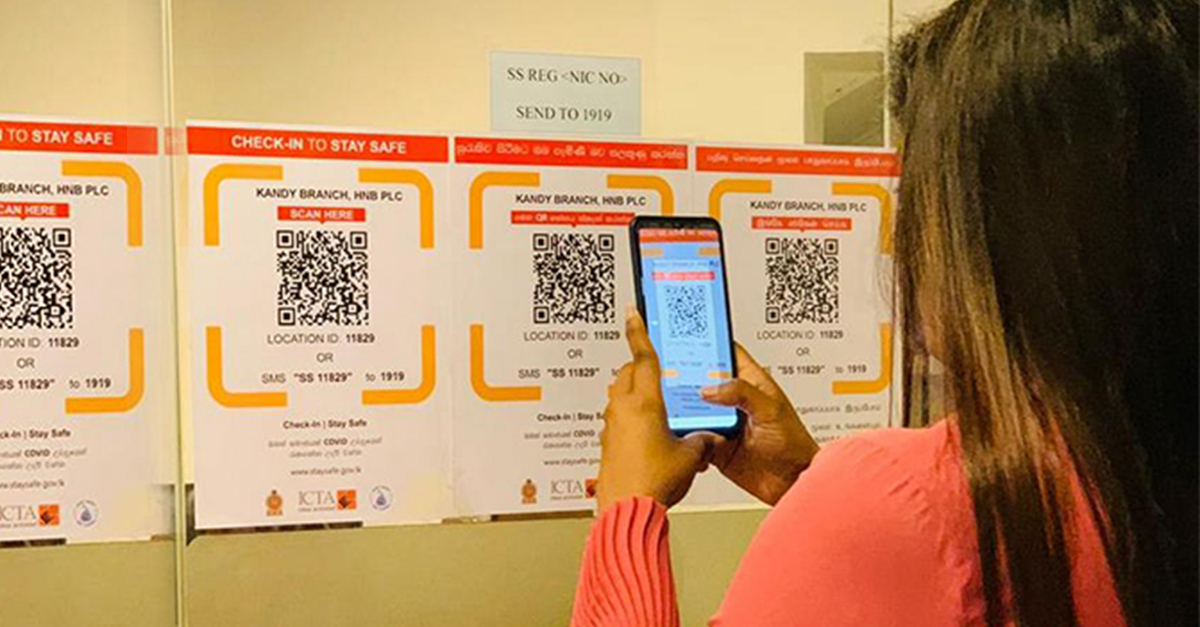

As other countries have done, Sri Lanka has also turned to technology to help curb the spread of the coronavirus. Developed by the state-owned Information Communication Technology Agency (ICTA), the ‘Stay Safe’ app is the Sri Lankan government’s tech solution for contact tracing on a national scale. Similar to New Zealand’s contact tracing app, ICTA’s app works via QR codes along with SMS, and is available in many public places today.

Although it may not be the answer to our prayers, it’s still a reasonable approach towards managing the COVID-19 situation in the country. However, the app’s security vulnerabilities leave much to be desired.

The Vulnerabilities Of It All

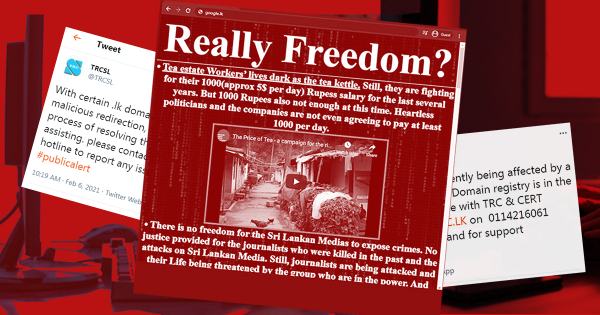

The vulnerabilities in question were raised on Twitter several weeks ago.

One of these allowed anyone to check submitted information on the service with an API call. ICTA later confirmed it had patched the reported loopholes, but this could be seen as an indication that cybersecurity was an afterthought — despite the project happening at a national level and dealing with citizen data.

One could point out that we already pose ourselves at risk each time we manually write our details in a book every time we enter public places. Yes, there is still risk involved. But this happening through a nationwide tech solution is far more dire.

For one thing, a project on the scale of Stay Safe comes with a much larger sample data size than what you would find on a physical book. Being a tech solution means potentially exposing this data to the whole of the internet. Should your data be compromised in such a scenario, the rate and scale your private information getting through to the public is exponentially high. This also means exponentially higher chances of cybercriminals using your data for malicious purposes. Comparatively, the impact of the same happening with details on a physical book is miniscule.

It’s like trying to adopt a lion as a pet as opposed to a stray cat. Sure, you could argue both are of the same type. But one of them is clearly more dangerous than the other.

Then again, Sri Lankan governments and cybersecurity have been two mutually exclusive sets for years. The president’s website hack in 2017, attacks on government websites in May this year, and even the eNIC project which envisages a digital database of citizens, all point towards the general lack of attention towards cybersecurity. The idea that government websites can be easily compromised or that a database of citizen information is being built with little mention of security measures is alarming to say the least.

The Cost Of Negligence

But is this really that important? Can we afford to worry about cybersecurity every time there is a government-level tech project? Yes, it is and yes, we should.

In 2019, hackers stole over 5 million taxpayers’ financial data in Bulgaria. A researcher claimed that the breach may have compromised the entire adult population in Bulgaria. In 2018, the Aadhaar identity database hack compromised nearly over a billion Indians’ biometric and personal data. Other grim examples have occurred in Greece, Australia, and the US.

Exposing private data at a national level by the millions, if not billions, leaves citizens at the mercy of cybercriminals. This can be as simple as losing access to your social media and email accounts, to something as dire as losing money from your bank accounts.

In this light, it’s not far fetched to imagine that Sri Lanka could suffer a similar fate should the worst happen. Are our cyber defences equipped to weather a storm?

Mind you, it is not a question of if, but when. Yes, there is a general reluctant attitude towards security at an individual level. But you can’t expect society to move in the right direction if authorities don’t take the initiative first.

Light At The End Of The Tunnel?

On a positive note, ICTA has updated its privacy policy for Stay Safe, notably around collection and usage of personal data. Accordingly, the retention period for personal data gathered via the ‘Stay Safe’ app will be 60 days, after which the data will be purged.

In the budget proposal for 2021, LKR 8 billion was allocated for the expansion of the tech sector in Sri Lanka — this could ideally include setting up the infrastructure to address data privacy and cybersecurity better. At the budget reading, Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa stated that there will be new laws for data and cybersecurity. All this could be taken to indicate the government intends to take cybersecurity seriously.

As of now, the draft bill of the Data Protection Act is underway and in its final stages. According to Jayantha de Silva, Chairman of ICTA, the Act is to be implemented in stages. And within three years after the date it gets passed by the Parliament, the Act will be implemented in full.

Not all of this is ideal, nor is it adequate given the present circumstances. As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, governments will continue to use technology to mitigate the virus. At the same time, more people will continue to adopt digital tools. Digital transformation is happening, even in Sri Lanka. The Stay Safe system is only a prelude. For ambitious projects like the eNIC initiative that is in the pipeline to truly succeed, cybersecurity and data privacy should not be a mere afterthought.