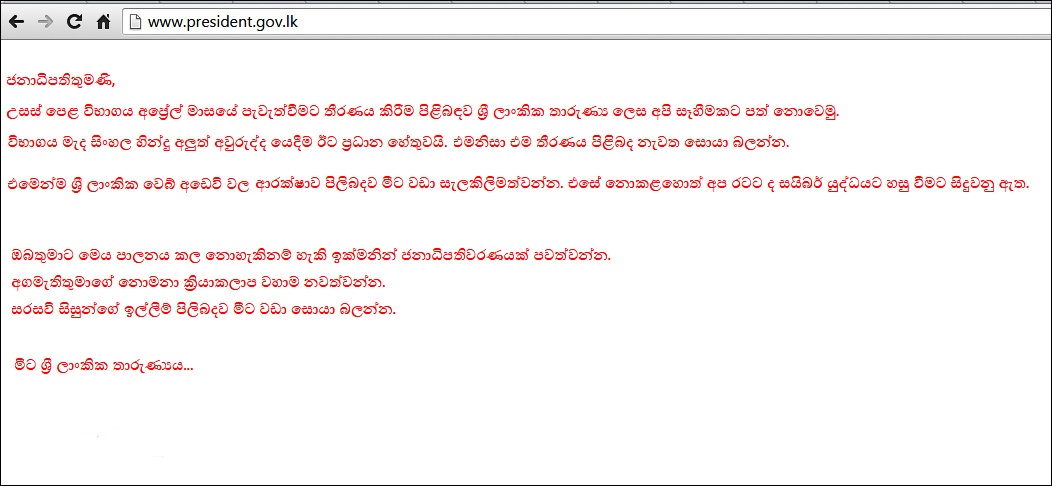

Last week, the President of Sri Lanka’s official website was hacked, not once but twice. The first attack was on August 25, and the follow-up came a day later, which is a bit embarrassing, really. Fool me once, shame on you ‒ fool me twice… The hack wasn’t all that malicious, and more like a polite “FYI”. This was the message that was posted on the site after the hack:

Hackers these days seem to have… interesting priorities. Image courtesy aluth.com

Basically, the hackers were asking the President to change exam dates, improve the security of Sri Lankan websites, stop the Prime Minister from being irresponsible, and look into the issues of university students. This is not exactly “fsociety” material, and indeed a 17-year-old student and 27-year-old man were arrested in relation to the hack. They probably barely hid their footprints after the hack.

This is not the first time that Sri Lankan websites have been hit either. In 2013, 22 Government websites were hit by the Bangladeshi Grey Hat Hackers, and in 2014, 129 sites (Government included) were hit in an Anonymous operation (#OpSriLanka) protesting the war. They were a bit late on that one. But the bigger issue seems to be that we just don’t take digital security very seriously. Hacking a website is not the most complicated task for a hacker; even election sites in the US are being hit right now. But there are security measures one can and must take to make a site more secure, especially after taking repeated hits. If you keep getting poked in the eye, and your only response is to wipe away the tears, then you’ve got problems.

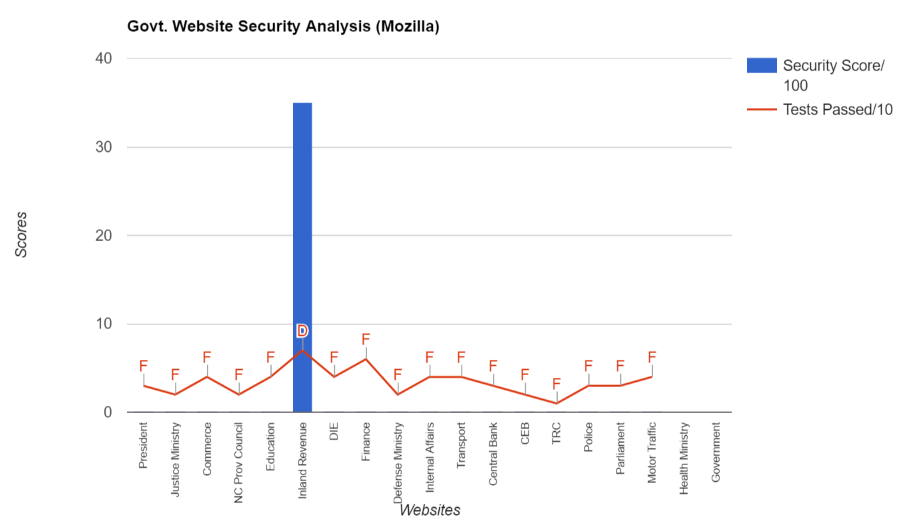

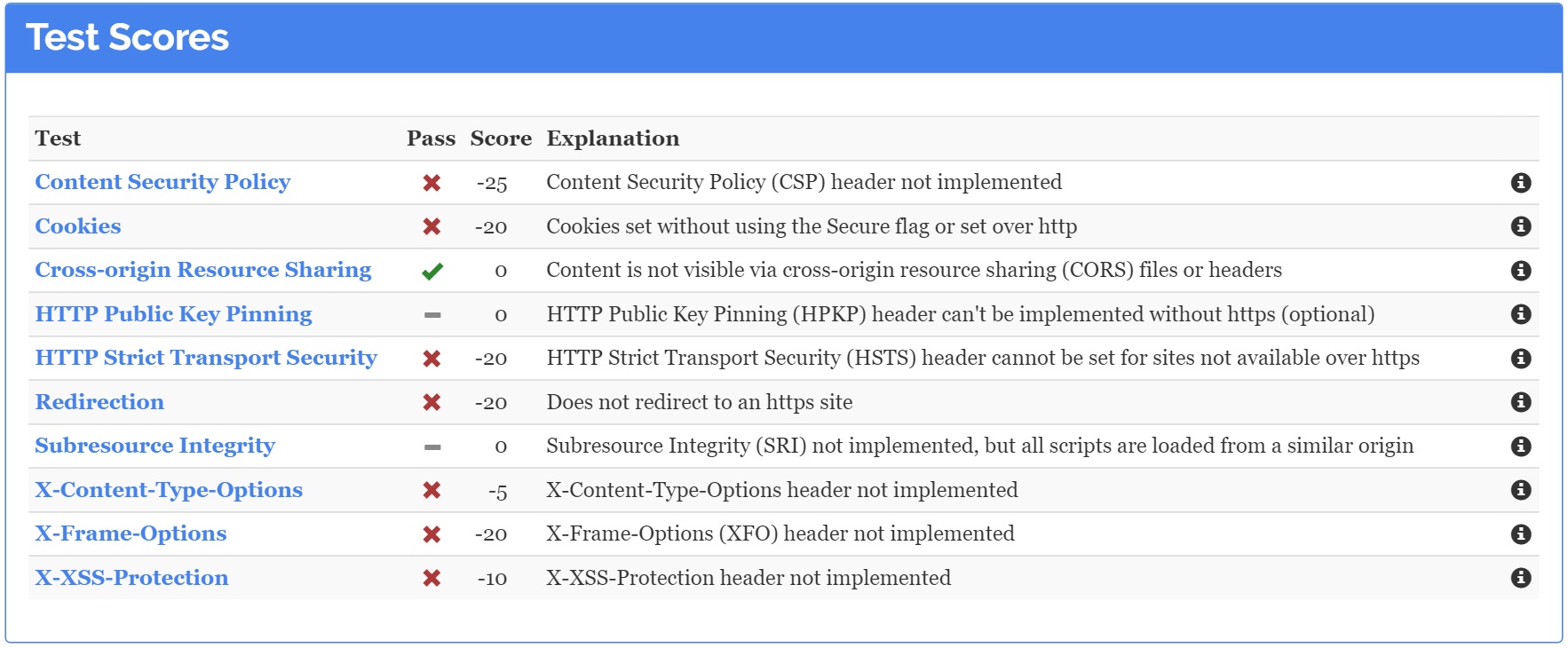

After the hack on the President’s website, we decided to take a look at his and other Government websites to see if they have taken measures to address security issues and bring their sites up to a reasonably modern standard of security, at the very least. Given that we don’t have access to any of their servers, the best we could do is use tools to scan the sites from the outside for compliance to security standards. Mozilla has developed a tool called Observatory, that is aimed at helping developers make sure their sites are safe and secure. We ran the websites through this tool, as well as a few others, to see how well they hold up against attacks.

Mozilla’s Observatory scoring is a bit on the tough side, and while not comprehensive ‒ it can be problematic to compare different types of sites and their security against each other ‒ it still is a good starting point to see if these sites meet current web security standards. For a deeper understanding of the methodology behind the testing, you can take a look at the tool’s FAQs. The individual tests are weighted differently, so some tests can score +10 or +5 while failing a test will get you a negative score, so the maximum number of points is a 130 while the minimum doesn’t drop below 0, no matter how bad the site is.

Sri Lankan Government websites graded by Mozilla Observatory

Looking at the graphic you notice one glaring feature ‒ the security scores for Government websites are terrible. Every single one of the 19 sites tested, with the exception of one, scores 0 out of 100. It seems like the Inland Revenue site is the only one that has implemented some decent security, scoring a 35 out of 100 and getting a respectable D grade. Every other site fails. The red line shows how many tests the sites have passed and most of them only passed 2 to 4 out of 10. That’s a failing grade for all except the Inland Revenue. The main Government website (https://www.gov.lk/) and the Health Ministry website don’t even show up on the scoring because the former has issues, and the latter didn’t have a valid URL ‒ just an IP address.

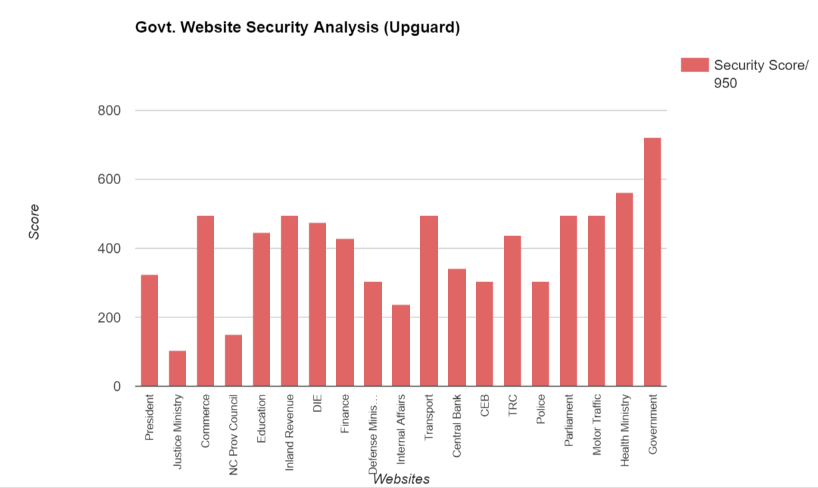

Just in case we are putting too much of our faith in Mozilla, we also tested the sites using UpGuard, since they are making big waves in the Cyber Security market right now.

Sri Lankan Government websites graded by Upguard

Here, the scores were a bit more even, with several other Government sites reaching the scores the Inland Revenue website had. Strangely enough, the gov.lk website scored really high, and so did the Health Ministry website. It’s probably a bug in the way the tool scans these sites, because none of the other tools were able to scan them (as mentioned before, the Health Ministry url is just an IP address), or if they did get scanned then they scored an F. The Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of Defense haven’t even updated their site descriptions properly. The former has a Joomla tagline while the latter includes a content line that goes “Easiest jQuery Tooltip Ever”. Okay, then.

Realising that we shouldn’t throw stones while living in glass houses, we did run roar.lk through the tests as well. Perhaps unsurprisingly, we didn’t do very well (and neither did many of the other media sites in Sri Lanka). We failed the Mozilla tests and scored average in the UpGuard tests. Something positive did come out of it, however. Because of this little experiment, we were able to pinpoint where we were lagging in security and make some changes to the site to rectify it.

The Government, on the other hand, has faced three hacking attacks (that we know of) in the last three years. You’d think they’d beef up security by now. Perhaps most of the sites don’t have very sensitive information in them, but they can still be a source of public embarrassment if hackers break in.

Website security is an issue worldwide. When the Observatory tool was first launched, Mozilla’s website failed its own test. Since then, out of 1.3 million sites scanned, 91% hadn’t implemented proper security. But companies are making improvements. Facebook scores a respectable B grade, Mozilla a C-, Google a D, and Microsoft a D. Our closest neighbour’s Government website (https://india.gov.in/) scores a C- though their President’s website still gets a failing grade.

The problem here is that the Government does not seem to be taking this very seriously. Days after the President’s site was hacked, it was still running outdated WordPress software, the server information (Apache) in its headers is not obscured, and Content Security Policy (CSP) headers are not implemented, so a hacker could technically trick the site into delivering malicious code (XSS attacks).

Multiple vulnerabilities

These very same issues plague the rest of their websites as well. No XSS protection, XFO header protection, or Content Security Policies, poor maintenance, and lack of updates make the majority of Government websites vulnerable. Now these are just external tests that can be done superficially to a website and don’t consider other points of weakness like the use of default passwords (“admin”), weak passwords (“12345”, “iluvmum”), human breaches in security, and social engineering attacks.

Anyone with a computer and a bit of Google search experience could have found out all of these details in an hour or two of work. An experienced hacker can do a whole lot more. Implementing security measures that protect sites against these sort of attacks are not an impossible task. If the Inland Revenue Department can do it, so can the other ministries. It just requires a bit of diligence, some planning, and a change in attitude. With Sri Lanka trying to make itself a tech and startup hub, the Government really can’t afford to drop the ball on this.

Featured image courtesy bluetext.com

.jpg?w=600)