Little is it known that the Arabs of old were a great maritime trading power. Their influence was far-reaching both in East and West. They played a very important role in the maritime silk route of the East that connected Africa with Asia, while their role in supplying prized merchandise to Western markets impacted European culture in more ways than one. English words of Arabic origin like ambergris, coffee, cotton, lemon, saffron, sofa, sugar, sherbet, talc and tamarind bear testimony to the profound influence Arabic had on Western tongues. The Arabs also contributed their share to the Sinhala language. Words like aluva (sweetmeat), kasav (gold lace), jabadu (musk), mosam (monsoon), malimaya (navigator) and rattala (pound) are of Arabic origin.

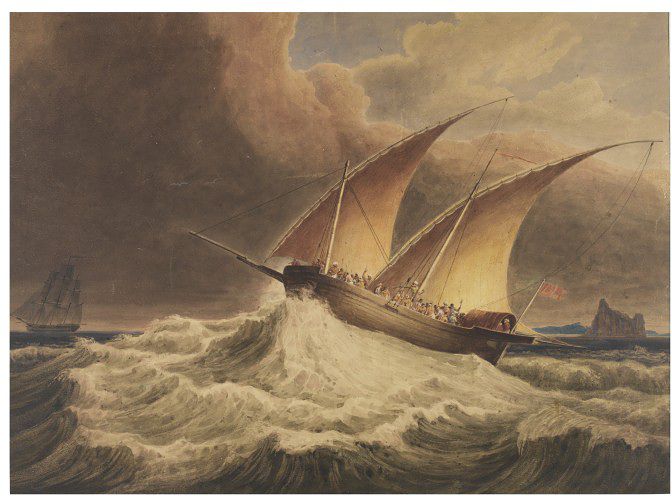

Water colour painting of Arab Dhow by William Danielle ( 1769 – 1837)

Sri Lanka figured prominently as an entrepot of trade in the maritime trading routes of the east, and over time the Arabs began to cultivate a profound love for our country. Arabian mariners often found their way to the island to visit Adam’s Peak which they regarded as the first home of the father of mankind, Adam, after his fall from paradise. Arabian merchants frequently came here to purchase cinnamon and precious stones that were in huge demand in Middle Eastern markets. Their love for our island is reflected in the many references to Sri Lanka scattered in their classical literature.

The Arabs of yore called Sri Lanka by two names, Sarandib (from Sanskrit Svarna-Dipa or ‘Golden Island’) and Sailan (from Pali Sihala ‘Island of the Sinhalese’ or Arabic Saylan ‘land of flowing waters’). The author of an old Arabic geographical work known as Mu‘jamul Buldan (Dictionary of Countries), Yaqoot Al-Hamawi (13th century) explaining Sarandib says that although he does not know what saran means, in the language of the Indians dib means ‘island’. It is therefore clear that dib is ‘island’ having derived from the word dipa meaning ‘island’. Saran could therefore have well derived from the word svarna or ‘golden’. This is corroborated by the Mahavamsa, an account of Sinhalese royalty which mentions nuggets of gold of various sizes found in the days of King Dutugemunu (C.2nd century BC). Gold still occurs in the stream sediments of Central, Southern and Western parts of Sri Lanka as dust, small flakes or nuggets. Nuggets weighing up to 16g have been found by gem miners in the Walawe Ganga near Balangoda.

Interestingly, it was this Arabic name of Sarandib given to our island that gave the English language the word serendipity coined by Horace Walpole in 1754 after the tale Three Princes of Serendip, which told the story of an adventurous trio who made discoveries by accident, of things they were not in quest of.

Another name by which Sri Lanka was known to the Arabs was Saylan. Ibn Shahryar, the author of the Ajaib Al-Hind (10th century) states that “This island of Sarandib is also known as Saheelan” which seems to suggest it took its name from Sihala, an old name for the island. However it is also possible that it could have well taken its name after our many streams and waterfalls, for it may be connected to the Arabic sayl ‘river’, ‘stream’. If so, it may well mean ‘the land of flowing waters’. Interestingly, the names given to the island by the European nations that colonized our island, including Portuguese Ceilao, Dutch Ceijlon and English Ceylon, are all derived from this Arabic term for our island Saylan.

Land of Father Adam

Adam’s Peak by Captain C. O. Brian. 1864

The mountain known as Adam’s Peak in the Ratnapura District has since time immemorial been called by local Muslims Baba Adam Malai or ‘Mountain of Father Adam’. This is because they believe that it bears at its summit the imprint of the foot of the father of mankind. This is also reflected in classical Arabic literature which holds that Adam descended on Sarandib and Eve in Jidda (which incidentally means ‘grandmother’ in Arabic) after their fall from paradise. The legend even influenced the story of Sindbad the Sailor, a relatively late addition to the Arabian Nights, which tells us that the island of Sarandib had the highest mountain in the whole world “on which our father Adam had lived for certain of his days”. A famous Turkish work, the Seyahatname of Evliya Çelebi (17th century) records a tradition that swallows roving over land and sea found Adam who was in Sri Lanka. “They brought a hair from his beard to Eve, who was then at Jedda, and a hair from Eve’s head to Adam in Ceylon. Thus the swallows became the mediators of reconciliation between Adam and Eve after their exile from Paradise. Adam and Eve then met on the tenth of the month Zilhejeh, on mount Arafat, near Mecca” (Narrative of Travels in Europe, Asia and Africa in the Seventeenth Century by Evliya Efendi. Translated by Joseph Von Hammer in 1846).

Many Arabian works support this story. A well known Arabian writer from Baghdad, Ibn Jawzi (12th century) says in his Muntazim: “The mountains of Sarandib are huge, among them is the mountain on which Adam descended from paradise and its name is Waash or Washim and people believe in that mountain is the imprint of the foot of Adam”. Likewise in the Tarikh Jurjan of Hamza Al-Jurjani (10th century), we read of a man named Abul Hasan Muharraz who claimed to have found in the country of Sarandib a stone inscribed with the words Uhbita Adam ‘(The place where) Adam descended’. The Tarikh Makka of Ibn Ziya (15th century) relates: “A man came for pilgrimage in Hijri 810 (AD 1407) and he said he had gone to the land of Sarandib. He had climbed on a mountain. He had started ascending in the morning and reached the summit by sunset. One climbs using chains of iron and there is the imprint of Adam”. But by far the most comprehensive account of the legend is by the famous Moroccan traveller, Ibn Battuta, who says in his travelogue, Tuhfat Al-Nuzzar (14th century): “The mountain of Sarandib is among the highest in the world; We saw it from the sea when we had still to travel nine days to reach it. When we ascended it, we saw clouds below us, hiding its base from our view. On this mountain there are many ever-green trees, flowers of many colours and a red rose as big as the palm of the hand. They say that on this rose there is an inscription of the name of the Almighty God and His Prophet. On the mountain there are two paths leading to the foot of Adam, called after the father and mother. Eve’s path is the easy route by which pilgrims return, and those who take it on their way to the Foot would be regarded as not having made the pilgrimage. Adam’s path is rough and difficult to climb. At the foot of the mountain, near the gate, is a grotto called after Alexander and a spring. The notable foot-print of our father Adam is on a high black rock in a roomy place. The foot has sunk in the stone so as to leave its imprint as a clear depression in the rock. It is eleven spans long”. (Voyages D’ Ibn Batoutah. Ed. C. Defremery & B.R.Sanguinetti (1858)).

Precious Stones

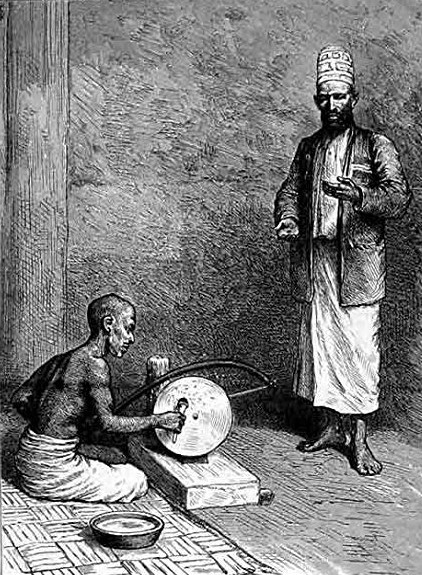

Illustration of Moor gem dealer descended from Arab merchants by Major General H.G.Robley. 1894

Precious stones from Sri Lanka had much demand in the thriving markets of the Middle East of those days. Especially in demand was a stone the Arabs called yaqoot, the name they gave to the ruby which they classed among the most precious of stones. It seems it was rubies that the island was most famous for. One of the names by which the island was known among the Arabs of old was Jazirat Al Yaqoot, meaning ‘Island of Rubies’, the name by which Al-Baladhuri, the author of the Futuh Al-Buldan (9th century) calls Sri Lanka. In the story of Sindbad the Sailor which took shape in the days of the Abbasid caliphs, we have Sindbad telling us that the King of Sarandib sent as a present to the Caliph Harun Al-Rashid (reigned 786-809) a cup of ruby a span high and adorned with precious pearls. Although the account is no doubt a fabulous one, it shows how much local rubies were esteemed by the Arabs of old.

We also read in the History of Tabari or Tarikh Al Tabari (10th century): “When Chosroes (6th century Persian King Khusrau Anushirwan) overcame Yemen, he turned towards Sarandib which is among the places of India and where is found the Land of Jewels (ardul jauhar)”. The Akhbar Ul Zaman of Masudi (10th century) says: “The last of the islands of this sea is Sarandib. It is in the ocean. In Sarandib are a good number of pearls (lulu) and jewels (jauhar)”. He adds: “In the mountains of Sarandib is a valley of diamonds (Wadi Almas)”. Ibn Jawzi says in his Muntazim (12th century) that a lot of rubies (yaqoot) and diamonds (almas) come from Sarandib.

It is interesting that some of these Arabian writers mention diamonds among the jewels the country produced. There is no evidence that diamonds were ever mined in Sri Lanka and it is possible that they mistook crystals of various kinds for diamonds.

Cinnamon

Cinnamon Peeling in Ceylon by Romeyn de Hooghe – 1682

True cinnamon is known in Arabic as qirfah sailaniyah meaning ‘Ceylon Cinnamon’. It is native to Sri Lanka and once had a huge demand in Middle Eastern markets. So famed was local cinnamon that it even found mention in the Alf Layla Wa Layla or ‘Thousand and One Nights’. For instance in the tale of Qamar Al-Zaman, where we find the ship’s captain telling Princess Budoor that he had in the hold “cinnamon from Sarandīb”. In the tale of Ala Al-Din Abu Shamat we hear of red cinnamon from Sarandib figuring in an aphrodisiac preparation. Here we are told of an aphrodisiac made of two ounces of Chinese cubebs, one ounce of fat extract of Ionian hemp, one ounce of fresh cloves and one ounce of red cinnamon from Sarandib, all mixed together and pounded before pure honey was added to it to form a thick paste.

The Arab merchants of yore did their best to keep the source of their cinnamon a secret. Herodotus in his Historia (5th century BC) says that cinnamon was collected by the Arabs who knew nothing of the country in which it was produced. He says “They can neither tell how, or in what region this aromatic is produced, and the best they can say is founded upon conjecture, some pretending that it grows in those countries where Bacchus received his education, and from thence, say they, certain great birds bring those sticks to build their nests, with a mixture of dirt in mountainous cliffs inaccessible to men. The Arabians, to surmount this difficulty, have invented the following artifice: they cut oxen, asses and other large cattle, into great pieces, and when they have carried and laid them down as near as is possible to the nests, they retire to some distance from the place. In the meantime, the birds descend to the flesh and carry up the pieces to their nests, which not being strong enough to support such a weight, fall down immediately to the ground. The Arabians approaching gather up the sticks and by this means they and other nations are furnished with cinnamon” (The History of Herodotus Translated from the Greek by Isaac Littlebury.1824).

It is very possible that such stories were invented by these ancient Arabian merchants so as to keep the source of the spice a secret, thus preserving their monopoly of the trade. And to think it all came from Sri Lanka!

The writer acknowledges Dr. S. M. Raeesudeen for translating some of the Arabic works cited here.

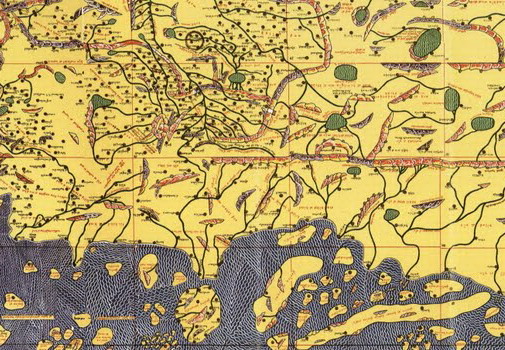

Cover image: Al Idrisi’s Map showing Sri Lanka as a large island (12th century)