The ruins of Sri Lanka’s ancient kingdoms are a testament to the architectural skill of our ancestors. They have several unique architectural features including intricately carved stairs, the moonstones that lie at the foot of the stairs, and the guard stones that are placed on either side of the stairs at the entrances to these historic and religious sites.

Among these, the guard stones, known as muragal in Sinhalese, are particularly fascinating. These features of Sinhalese architecture have both practical and decorative purposes.

The purpose of a guard stone

Some academics believe that the concept of guard stones found its way to Sri Lanka from India. Image courtesy davidaolson.wordpress.com

Over the years, many theories about the true purpose of a guardstone have been put forward by historians and archaeologists.

Some archaeologists, like Dr. Charles Godakumbura, former commissioner of the Department of Archaeology in Colombo, have stated that guard stones were designed to protect the balustrade (korawakgala) that runs along the side of the stairs at the entrance.

Others like Professor Chandra Wickramage, the head of the editorial team that authored the latest volume of the Mahawamsa, criticise this theory, suggesting that guard stones merely had a decorative purpose, as features of the entrance to ancient buildings of social and religious importance.

Guard stones and gatekeepers

Because guard stones have only been found at the entrance to temples and royal palaces, there is a belief among many people that they were installed for protection from thieves and evil spirits.

Even though guard stones are considered a unique feature of Sinhalese architecture, some academics believe that they were originally influenced by Indian art and architecture. For instance, the paintings of ‘gatekeepers’ at the Ajanta cave temple bear similarities with the guard stones. Therefore, it is quite possible that this symbolic concept of guarding doorways may have found its way to Sri Lanka from India.

The evolution of guard stones

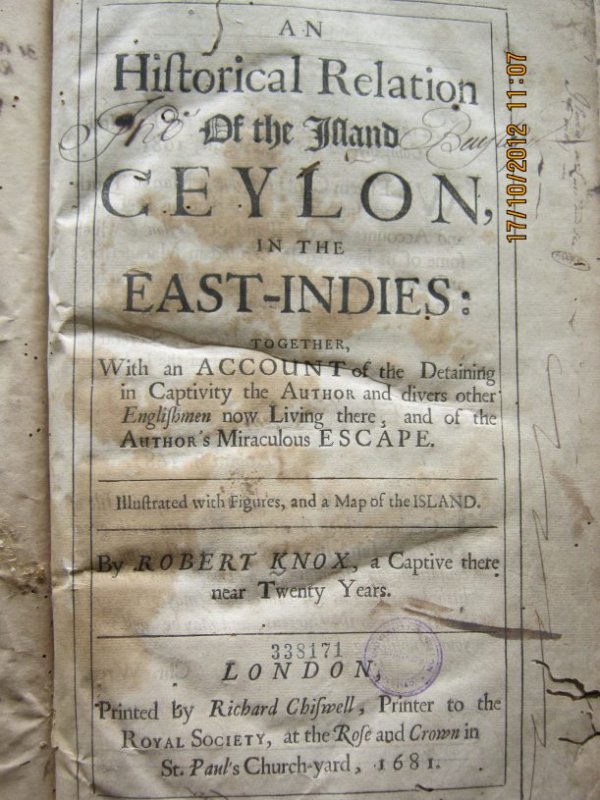

The earliest guard stones were plain and uncarved. Image courtesy si.wikipedia.org

The very earliest guard stones, moonstones and balustrades, were created with pieces of valuable wood. Many of the early guard stones were uncarved, and archaeologists now use this detail to identify the age of some historic buildings.

Speaking to Roar Media, archaeologist Professor Nimal de Silva said that the earliest guard stones date back to about the 1st century A.D—the early period of the Anuradhapura Kingdom.

Over time, the architects of the Anuradhapura kingdom used stone, instead of wood, for the construction of guard stones, moonstones and balustrades, as stone was a more enduring material.

The next stage in the evolution of the guard stones was the inclusion of carvings. It is, however, difficult to pinpoint the exact time period when these changes began to take place as research is still being conducted.

Four different motifs have been identified on guard stones: the punkalasa (or pot of flowers which symbolises prosperity), the dwarf or eunuch, the serpent with multiple heads and the naga raja or serpent king.

Where you can find these motifs

The punkalasa is a symbol of prosperity. Image courtesy thilankams.blogspot.com

The guard stone with the image of the punkalasa can be seen at the Ras Vehera cave temple in Anuradhapura, the Welgam Vehera in Kanniya, the Magul Maha Vihara in Lahugala and even at the Kaludiya Pokuna at Mihintale.

Professor Nimal de Silva noted that while guard stones are mostly found at the entrances of temples, monasteries and royal palaces, it is not unusual to find this architectural feature at entrance of sites such as the Kaludiya Pokuna bathing pond.

Another example of this motif is the northern doorway of the convention hall at the Abhayagiri Viharaya, which features a guard stone with images of a punkalasa and a kapruka (a mythical tree with magical powers).

Archaeologists, however, consider the guard stone at Toluvila in Anuradhapura as the best example of a guard stone bearing the symbol of prosperity.

The images of the dwarves may have been carved onto guard stones to protect valuable relics housed inside stupas and viharas. Image courtesy si.wikipedia.org

During the middle period (2nd century A.D. – 6th century A.D.) and the latter period (7th century A.D. – 11th century A.D.) of the Anuradhapura kingdom, stone workers began to carve the image of a dwarf on the guard stones. This was due to the rural superstition that dwarves, known as vamana in Sinhalese, had magical powers and were the protectors of treasure.

This belief stems from the Meghaduta, a Sanskrit poem written by the poet Kalidasa, which speaks of two dwarves by the name of Sankha and Padma who were the guardians of the treasure that belonged to Kuvera, the god of wealth and prosperity.

The guard stone depicting the dwarf Sankha can be identified by a small carving of a conch shell, while the companion guard stone depicting the dwarf Padma would include the carving of a lotus bloom.

Professor de Silva noted that the purpose of carving such an image on guard stones may have been to protect valuable items and relics that were housed inside places of religious veneration.

“The symbols of the conch and the lotus were not only associated with Sankha and Padma,” stated Professor de Silva. “The conch and lotus were the symbols of God Brahma as well, and he, along with the God Sakra, gave protection to Lord Buddha.”

The guard stones bearing the images of these dwarfs can be found at the Abhayagiri Temple, the Wijerama Vihara Geya in Anuradhapura and the Rajagiri cave temple of Mihintale.

The serpents featured on the guard stones of the latter period of the Anuradhapura kingdom had several heads. Image courtesy si.wikipedia.org

Towards the latter stages of the Anuradhapura Kingdom, guard stones with the images of serpents or cobras were carved. These images featured serpents with five or seven heads. The most notable example of such a guardstone is the one at the Kuttam Pokuna in Anuradhapura.

The ancient Sinhalese people considered the serpent to be a deity with power over water, and this could be the reason why many of the guard stones bearing the images of serpents have been found at places situated near bodies of water.

There are many theories about the multiple heads of the serpents on these guard stones. Some archaeologists and historians believe that the carvings of the five-headed serpent may be symbolic of the five senses—sight, smell, sound, taste and touch—which, according to Buddhism, allow a person to feel desire.

Professor de Silva, however, believes that the number of heads in the serpent images were decorative and not symbolic.

The naga raja guard stones were carved with the image of the serpent king or naga raja. Image courtesy wikipedia.org

The guard stone with the image of the naga raja is the best known of all guard stones of Sri Lanka. As Professor de Silva noted, the naga raja guard stones were carved with the image of a serpent king, a protective deity who was revered by the ancients. The naga raja were also referred to as naga dwarapala in the Sanskrit language.

The naga raja guard stones depict a male figure with a five or seven-headed serpent hood holding a punkalasa in one hand, with a dwarf or two dwarves standing near the feet of the serpent king. The entrance of the Rathna Prasadaya of Anuradhapura has a beautifully preserved naga raja guard stone which is believed to have been carved during the days of King Mihindu.

While many theories surrounding the artistic components of the guard stones are suggestions and speculations, it is important to note that many historians and archaeologists believe that the naga raja guard stones are a combination of the ones that were carved before it. With research still ongoing, the debate around the guard stones are bound to provide new insights into the lives and times of the ancients.

*Research by Dharani Weerasinghe

Featured image courtesy flickr.com