Have you ever read a book about a place you’ve never seen? Did you find yourself being enthralled by its vivid descriptions of creatures and trees and people you never knew could exist? If you have, you would agree that an author’s artful use of language has the power to connect you to a whole other world, to such an extent that by the time you reach the end of your book, you are justifiably convinced that you have travelled – across multiple dimensions – and have physically seen and experienced a reality, which will form part of your language and thinking from that point on.

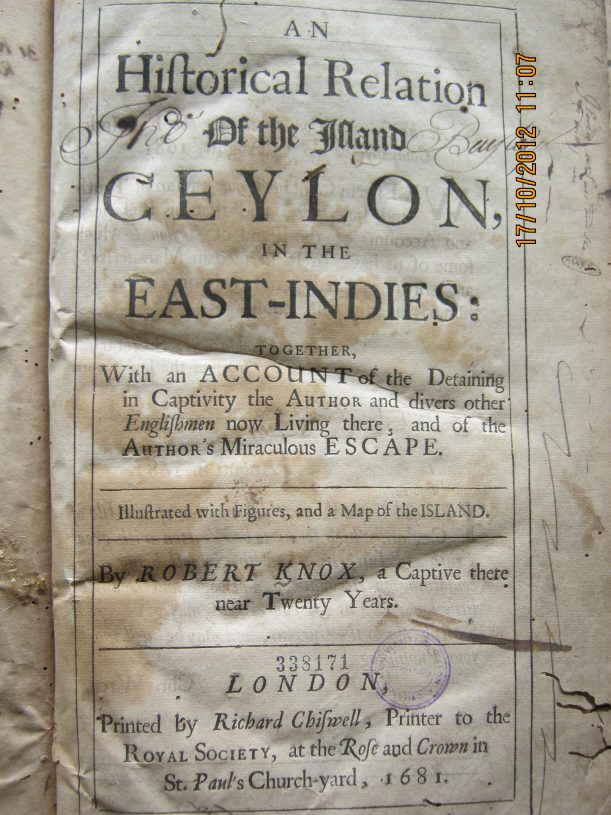

This is likely to have been how 17th century Londoners felt when they finished reading a copy of Robert Knox’s book, An Historical Relation of the Island of Ceylon (An Historical Relation) – the first book ever to be written on the subject of Sri Lanka in the English language.

Who Was Robert Knox And How Was He Qualified To Write About Sri Lanka?

Born in London, on 08 February 1641, Robert Knox was the son of an East India Company captain, also called Robert. Having possessed a passion to go out to sea from a very young age, Robert Knox began a career in seafaring, alongside his father. At just 17, he set sail for the East Indies, on the Ann, under the colours of the East India Company. On this voyage, Robert Knox was given the responsibility of maintaining the ship’s log, little knowing that it would be his writing skills – and not the strength of his seafaring – that would see him through the extraordinary events that lay ahead of him.

On 19 November 1659, the Ann was caught in a cyclone off the coast of South India, causing Captain Knox to steer her off-course, to Koddiyar Bay, on the east coast of Sri Lanka, then called Ceylon, where it was hoped she could be repaired.

When Robert Knox stepped off the Ann, he stepped, unwittingly, into a chapter of one of Sri Lanka’s most tangled political eras; while the Kandyan Kingdom was still an impenetrable stronghold, the Dutch held the maritime provinces of Ceylon. Therefore, unbeknownst to Robert Knox, two dangers lurked beyond the happy shallow waters of Koddiyar Bay: one was the danger of the Dutch arresting the Ann on account of her being a British vessel, and the other was the danger of King Rajasingha II (1612-1687) of the Kandyan Kingdom detaining the crew.

The latter transpired, and Robert Knox found that he was one of 16 men from the crew held captive by the Kandyan ruler, who split them up and billeted them in different villages in the Kandyan Kingdom. His father, Captain Knox, also held captive, died of malaria, in the village of Bandara Koswatta, near Wariyapola, a few months into his captivity, in 1661.

King Rajasingha wearing a costume with “a long band hanging down his back of Portuguese fashion” from Robert Knox’s An Historical Relation. Image credit serendib.btoptions.lk

King Rajasingha wearing a costume with “a long band hanging down his back of Portuguese fashion” from Robert Knox’s An Historical Relation. Image credit serendib.btoptions.lk

Robert Knox was to spend the next 22 years of his young life incarcerated in Ceylon. However, being possessed of an attitude that seems so sparse in today’s world, Robert Knox found the strength to integrate with the community he was placed in. He began to make a small living from rearing poultry, and knitting caps for sale, while learning the language and observing the culture of the community, almost as if he was an insider. It would seem that his primary occupation was to study and master his surroundings, if only to survive.

How Did Robert Knox End Up Writing An Historical Relation?

For a large portion of his time in Ceylon, Robert Knox had with him two books (just two!) to occupy his mind, and to keep him in touch with the English language. Both books, A Practice of Piety and The Practice of Christianity were books he had brought with him from the Ann. Fortunately for us, Robert Knox managed to get his hands on a third book – an English Bible – which he obtained by barter (in exchange for a knitted cap) from an old man who had acquired the same from a Portuguese man who had left Ceylon. It is speculated that Robert Knox’s constant reading of this rich and varied narrative enabled him to develop the prose style which made An Historical Relation so readable in its day.

However, Robert Knox did not have the opportunity to write while in captivity. It was many years later, in January 1680, when, after having escaped from the Kandyan Kingdom and into Dutch territory, and having the joy of being once more at sea, on board the Caesar, which was headed to his homeland, that Robert Knox began to write his account of Ceylon. Having not held a pen in two decades, Robert Knox more or less taught himself to write again – and – given the impact of his work – we are evermore thankful that he did!

On his return to Britain, and having received the measly sum of twenty guineas from the British East India Company as compensation for the decades he spent in captivity, Robert Knox found he was “destitute both of money and friends” in his very home country (Paulusz,1989). However, he soon reintegrated into society (as he had done in his years of captivity), with the help of his brother James Knox, who introduced him to the clientele of a fashionable coffee house called ‘Garraway’s’ in London. Through the inroads of relationships built over coffee, Robert Knox mustered the courage to submit his writings to his employers, the East India Company. It was in this manner that, in 1681, Robert Knox’s magnificent account of Ceylon was published in London.

What Kind Of An Impact Did An Historical Relation Make?

From the research collection at the library of The University of Colombo. Image courtesy lib.cmb.ac.lk

From the research collection at the library of The University of Colombo. Image courtesy lib.cmb.ac.lk

It would be fair to conclude that An Historical Relation was the ideal mix of an adventure filled autobiography and an exotic travel guide – so much so, that it was an immediate hit. It enhanced British comprehension of Ceylon at a time when such knowledge was relished, and it introduced to the world, many exotic words of Sri Lankan origin or association. Robert Knox accomplished this by the extraordinary skill with which he described objects, creatures, and situations that were entirely alien to British imagination. Take a look, for example, at how he described the betel-leaf:

“The tree that bears the betel-leaf, (which is so much loved and eaten in these parts) grows like Ivy, (twining about Trees, or Poles…The form of the leaf is longish, the end somewhat sharp, broadest next to the stalk, of a bright green, very smooth, just like a Pepper leaf, onely different in the colour, the Pepper leaf being of a dark green.)”

It really should not surprise us to learn that An Historical Relation is responsible for permanently housing 18 words of Sinhala origin in the second edition of the Oxford English Dictionary. These words have an exclusive or very close association with Sri Lanka, and include betel-leaf, bo tree, Buddha, rattan, Vedda, and wanderoo.

Robert Knox also provided the first occurrence in English literature of unusual senses of 11 English words (an example being the word dodge, which he used to describe the way he saw people in Ceylon eluding a charging elephant!).

While An Historical Relation was widely read in London, when it was first published, it was later also translated into German (1689), Dutch (1692) and French (1693), making its impact even more widespread.

Quite apart from this linguistic contribution, it is also important to note that Robert Knox’s story of captivity and survival also caused ripples in and of itself. It sparked the imaginations of many who heard it at Garraway’s or via An Historical Relation, to such an extent that it greatly influenced the creative writing that emerged from his time. For example, when you first heard the story of Robert Knox – how he was stranded on our island, far away from everything and everyone he knew – you may have found it rather similar to the story set out in Daniel Defoe’s ‘Robinson Crusoe.’ Judging from the storyline, the stoic character of its protagonist, and the descriptions used in Robinson Crusoe, it would seem obvious that Daniel Defoe, a contemporary of Robert Knox, was indebted to Robert Knox and his An Historical Relation. Although this is, arguably, a somewhat speculative theory put forward by scholars, a few things are certain: the first is that it is established fact that Daniel Defoe owned a copy of Robert Knox’s An Historical Relation (Ferguson, 1896), and second is that his Robinson Crusoe was published in the immediate aftermath of An Historical Relation. Sadly, it is unclear as to whether Robert Knox ever had the chance to read Robinson Crusoe, as he died the year following its publication.

As an aside, perhaps you would be intrigued to know that Robinson Crusoe, published in 1719, is hailed as the first English novel, and is therefore seen as the Godfather of an entire genre of castaway/adventure fiction. In this light, it may not take too much of a stretch of imagination to think it’s influence, and indirectly, the influence of Robert Knox (and Sri Lanka!), still reaches the world today, in the form of popular fiction such as Hollywood’s Castaway, starring Tom Hanks, in the year 2000. Now how is that for impact?

Tom Hanks as Chuck Noland in Cast Away. Image credit www.popmatters.com

Tom Hanks as Chuck Noland in Cast Away. Image credit www.popmatters.com

What Are Some Insights We Can Get Into 17th Century Ceylon From An Historical Relation?

There is much to be seen of old Ceylon through the eyes of the British captive, Robert Knox. A few pickings, for your pleasure, are set out below (mind ye olde English):

- On what was on the menu at the time, he noted:

“They have several other sorts of fruits which they dress and eat with their Rice, and tast very savoury, called Carowela, Wattacul, Morongo, Cacorebouns &c., the which I cannot compare to any things that grow here in England.”

- On the problem of leeches, he observed:

“These Countries are very healthey and pleasant – onely in times of rains they are much annoyed with… Land Leeches.”

However, our favourite Robert Knox snippets are those which pertain to betel leaves. On the practice of chewing betel in Ceylon, Robert Knox had the following to say:

“The better sort of Women, as Gentlewoman or Ladies, have no other Pastime but to sit and chew Betel, swallowing the spittle, and spitting out the rest. And when friends come to see and visit one the other, they have as good Society thus to sit and chew Betel, as we have to drink Wine together.”

We consider it apt to close with Robert Knox’s (rather amusing) thesis on why the inhabitants of this island loved to chew betel at the time:

“And the Reasons why they thus eat it are, First, Because it is wholsom. Secondly, To keep their mouths perfumed: for being chewed it casts a brave scent. And Thirdly, To make their Teeth black. For they abhor white Teeth saying, That is like a Dog.”

[Sources include ‘Knox’s Words,’ by Richard Boyle (2004), and ‘Ceylon of the Early Travelers’ by H. A. J. Hulugalle (1965)]

Cover image courtesy lib.cmb.ac.lk