Sri Lanka’s political landscape of the 20th century was dominated for the most part by a handful of prestigious families. These included the Bandaranaikes and the Wijewardenes, whose members were among the most powerful and influential in the country (and perhaps still are, to this day).

While the Wijewardene name is often associated with the newspaper industry, ‘Bandaranaike’ almost always calls to mind Sri Lankan politics of the last six decades. Before the family name became a political legacy, however, it was connected to a stately mansion: the Horagolla Walauwa in Aththanagalla, a suburb in Gampaha.

The Origins Of A Legacy

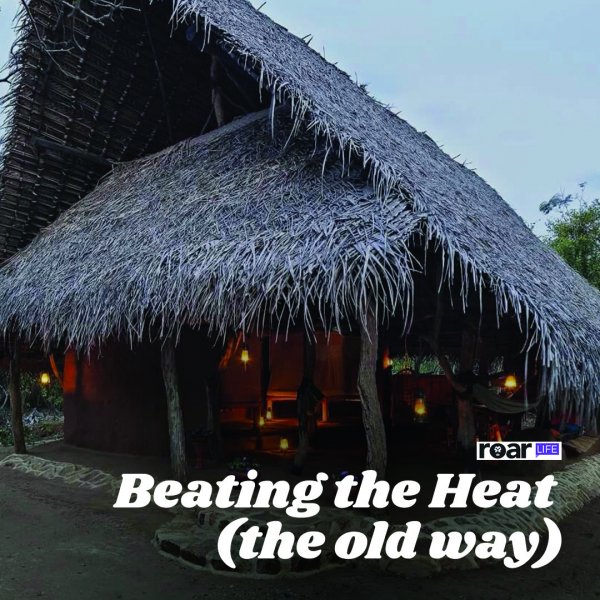

During the colonial occupation of Ceylon, certain families were awarded titles such as ‘Maha Mudaliyar’ (referring to the chief of the ‘native headman system’ used by the colonisers) for their loyalty towards the administration. These feudal families were often well-laden with property and lived in stately homes that were known by the locals as ‘walauwas’.

The Bandaranaikes were one such feudal family. Records indicate that sometime around 1820, a local headman by the name of Don Solomon Dias Bandaranaike was granted a 175-acre land in Horagolla by the British government for his assistance in the construction of the Kandy Road, particularly the section between Colombo and Veyangoda. One day, Don Solomon is said to have found a turtle (kiri ibba) on his land and, believing it to be a good omen, decided to construct his house at the location. Though many do not know it, this house was the original Horagolla Walauwa.

Prosperity and luck followed the Bandaranaikes. Within three generations, the family’s portfolio of lands grew to exceed 3,000 acres — an astounding number considering the social system at the time. It was Don Solomon’s grandson, Sir Solomon Dias Bandaranaike, born on 22 May 1862, who inherited all these.

Not one to fritter away his inheritance, Sir Solomon spent his adult years rising up the social ladder. By 1882, he was appointed a Muhandiram of the Governor’s Gate — an honourary title. By the time he was 33 years old, Sir Solomon was elevated to the position of Maha Mudaliyar by then Governor of Ceylon Sir Arthur Havelock.

It was around this time that Sir Solomon decided that he did not want to live in his grandfather’s house anymore, so he built a new house on an adjacent plot of land. This relatively newer building is the Horagolla Walauwa that we know and speak of today.

An Abode Fit For Royalty

In building his house, Sir Solomon spared no expense. Architects were brought down from England and builders were hired both locally and from India. Wood, ceramics, glass panes, copper and other materials were imported from all over the world, especially from Europe.

The Horagolla Walauwa is reflective of the expensive tastes of its first owner in many ways. Be it the imposing, airy porch or the large, spacious hall that can easily host a small party of visitors, almost every square inch of the house conveys a sense of old-world grandeur and opulence.

Take, for instance, the upper floor of the walauwa, where the sleeping quarters of the Bandaranaikes are located. Even during a time when many locals did not have access to proper sanitary facilities, Sir Solomon made sure that every room in his house had an attached bathroom.

Placed all around the house are interesting little trinkets, mementos, photographs, and paintings that serve as reminders of the vast number of historically significant incidents that the house has no doubt borne witness to.

Today however, the famed Horagolla Walauwa is very much reflective of the political fortunes of the family that occupies it. Gone is the sense of awe that often overcame Sri Lankans whenever an image of the house appeared in newspapers or on television. Instead, it is replaced by a silent sense of acknowledgement, perhaps a sign that Sri Lanka has fallen out of love with the walauwa that once housed the kingmakers of Sri Lankan politics.