Don Bradman receives a souvenir from “the Wisden of the East”, S.P. Foenander, Sports Editor, Ceylon Observer, October 1930. Image courtesy State Library of South Australia

On 5 September 1832, a notice appearing in the Colombo Journal inviting “gentlemen who may be inclined towards forming a Cricket Club” to attend a meeting at the Colombo Library three days later, resulted in the formation of the Colombo Cricket Club (C.C.C.). Shortly after, the first recorded cricket match in Sri Lanka took place between the C.C.C. and the British 97th Regiment of Foot (now the Princess of Wales’s Royal Regiment), on the Rifle Green in Slave Island. The C.C.C. faded away afterward, but revived in 1863.

Ethnic Cricket

The players on both sides were all White British—in fact, the C.C.C. remained European-only until 1962. British planters formed the Radella Club (officially Dimbula Athletic and Cricket Club) in 1856, and the Darawella Club (Dickoya Maskeliya Cricket Club) in 1868—which year saw the first Dimbulla-Dickoya cricket encounter. Other, all-European outstations clubs, such as the Athletics, Boating, Cricket, and Dancing (A.B.C.D.) Club—now the Kandy Sports Club—followed.

However, the locals began to pick up the game after its introduction at the Colombo Academy (now Royal College) in 1838. In 1879, the first inter-school cricket match between the Colombo Academy and St. Thomas’ College inaugurated the second longest uninterrupted school cricket series in the world: the Royal-Thomian.

Galle Face Cricket Ground HW Cave; Caption: Galle Face Cricket Ground, from H.W. Cave’s Book of Ceylon

Meanwhile, non-European clubs began to be formed mainly on ethnic lines. The Malay soldiers of the Ceylon Rifle Regiment, quartered next to the Rifle Green, came to love the sport through watching the British playing it. They formed the Malay Sports Club in 1872, on a corner of the Green. The (mainly Burgher) Colombo Colts followed the next year; their ground, the “Racquet Court”, came to be known as “the cradle of Ceylonese cricket”. The Singhalese Sports Club (S.S.C.) and Tamil Union followed in 1899; Moors’ in 1908; and the refreshingly non-ethnic Nondescripts (N.C.C.), open to all Sri Lankans, in 1891.

Ashes Teams

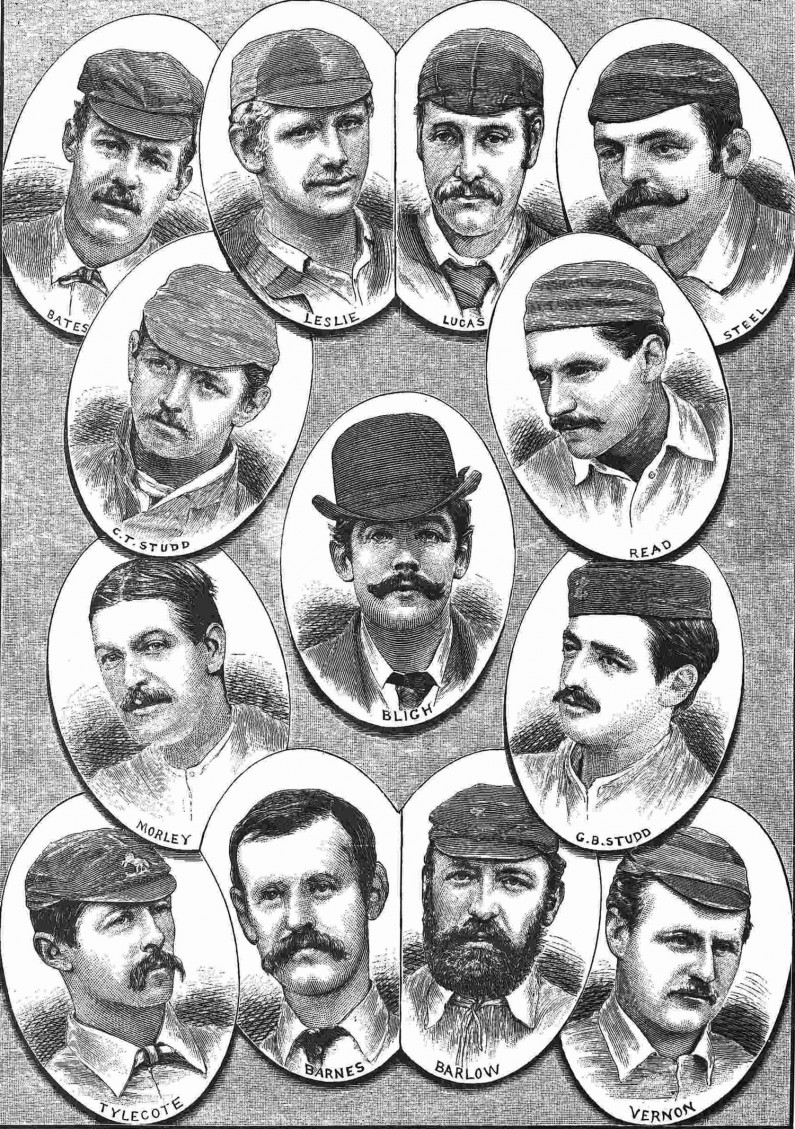

England’s defeat by the Australians in 1882 led to the fixtures against Australia being dubbed “Ashes” tests, from the “ashes” of the England team. Within a fortnight of that defeat, an England team led by Ivo Bligh set out for Australia to “regain the ashes”. They stopped in Colombo on 13 October and played a two-day game against C.C.C.

In the 19th century, inexperienced teams commonly fielded more players, in so-called “odds” games. In this match, in which Bligh, being unwell, could not take part, the England Eleven faced 18 C.C.C. players. C.C.C. scored 92 and 16 for 7, the visitors replying with 155 for a draw. This, Sri Lanka’s first game against an overseas side, inaugurated a tradition of Ashes teams stopping over in Colombo to play local teams.

Ivo Bligh’s Ashes squad, from the Australasian. Image courtesy Wikipedia

Unofficial tests

In April 1884, the Australian Ashes team, led by Billy Murdoch, arrived in Colombo. After a tour of the sights, including a visit to the exiled “disturber of Egypt”, Arabi Pasha, the team played an odds game against Colombo on Galle Face Green, watched by

“between 4000 and 5000 persons, white and black, well dressed, half dressed and some boasting the sole adornment of a cloth round the loins… Large numbers of the military were interspersed through the crowd, their snow white uniform forming a grateful contrast to the glaring red and yellow affected by the natives…”

In 1889, G.F. Vernon led an all-amateur England team which toured the subcontinent, the first to visit India. The team played the first ever “unofficial test” against an (all-European) All-Ceylon team in Kandy. In reply to All-Ceylon’s 155, the visitors scored 234 for 8, anchored by Vernon’s 105 not out. Thereafter, all international matches played by the Sri Lanka team until 1981 were to be “unofficial tests”. England teams playing All-Ceylon were labeled M.C.C. (for Marylebone Cricket Club), reflecting the “unofficial” status of the tests they played.

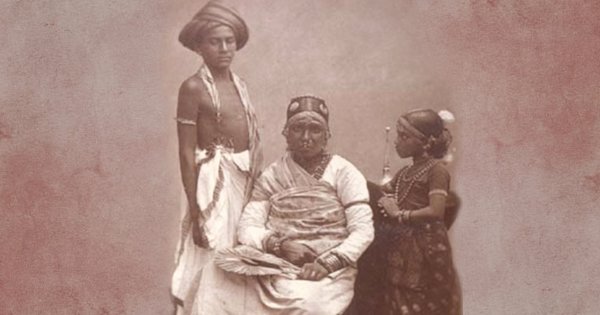

Billy Murdoch keeping wicket. Image courtesy State Library of Victoria

W.G. Grace

Cricket was evolving slowly into an expression of national (as opposed to ethnic) pride, as Sri Lankans became more confident at the wicket. In 1887 an annual fixture began, lasting until 1933, in which the “Europeans” played the “Ceylonese”, the latter being more often victorious. This led to the progressive indigenisation of the All-Ceylon team.

When the Australians returned in 1890, they faced a team which, for the first time, had equal numbers and also included Burghers, so they faced Asians for the first time ever. Playing in front of 6,000 spectators on Galle Face Green, the Australians piled on 187 runs, and the locals replied with 95. As usual at the time, the Australian team was not at full strength, so the numbers were made up of the passengers and crew of their ship.

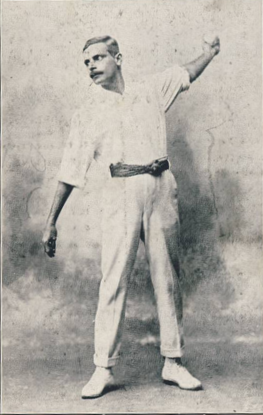

The next year, W.G. Grace’s England XI took the field against an All-Ceylon XVIII. Facing Tommy Kelaart, Grace, with 14 runs under his belt, hit his own wicket and left the crease, despite the umpire ruling him not out—the only time he ever did so. Kelaart, considered Sri Lanka’s best-ever left-arm spin bowler, went on to take over 2,000 wickets in a career spanning 36 years.

In 1894 the M.C.C. XI led by Andrew Stoddart played a test in Colombo in 1894, being remarkable because a local player, Alan Raffel, clean bowled ten players, including Stoddart, with a tally for the match of 14 for 97. It was also the last M.C.C. match on the island for 14 years: although the England Ashes team did visit the island, they did not play any matches. Similarly, following an Australian match in 1896, an 11-year hiatus occurred in tours by antipodean teams.

Tommy Kelaart, from P Bartholemewsz’ Ceylon’s Champion Bowler – A Sketch of Tommy Kelart

India, the Straits, and Boers

Sri Lankan cricketers filled the vacuum by playing regional neighbours. The first Sri Lankan tour of India took place in 1884, to Kolkata, the first ever international match in India. The next year the team visited Bangalore and in 1886-87 toured Mumbai, Agra, and Peshawar. These Sri Lankan teams were European. In 1890, a Sri Lankan team (including two Burghers) toured the Straits Settlement (as Malaysia and Singapore were known then). In turn, Sri Lanka hosted teams from the Straits, Mumbai, and Madras. In 1903, two Sri Lankans, Tommy Kelaart and Douglas de Saram, were selected to represent India in a tour of England, which unfortunately proved abortive, for want of funds.The first all-indigenous team toured Mumbai in 1906, winning three of six matches and drawing the rest.

The over 5,000 Boer War prisoners held in Sri Lanka, also helped fill the gap, playing a game against the Colts in Colombo, and an odds game against a local XVIII at Diyatalawa. These were the first matches ever played in the subcontinent by South Africans.

The Boer team poses with the Colts

Racial Storm

When matches against Ashes teams resumed in 1908, the six professional members of the England team (including Jack Hobbs) refused to play All-Ceylon without payment of £10 each. The C.C.C., which organised the match refused to pay, so the amateurs cobbled together a team which played an indigenous one.

The Australians touring the next year also demanded payment, which the C.C.C. refused, so the S.S.C. organised a gate and paid them £10 each. Consequently the European cricketers refused to play, which in turn resulted in a non-European team beating the Australians in two games, the first time All-Ceylon had won against Australia. This caused a racial storm, the London Truth calling it “a degrading match against a purely native team, which degraded the white man in the native’s eyes.”

In the next few years, these racial tensions simmering below the surface boiled to the top, exacerbated by the “White Australia” policy. In 1913, a Sri Lankan doctor, Christian Victor Aserappa, working as ship’s doctor on the Orontes, was discontinued on the ship’s arrival in Fremantle following protests in the Australian Parliament. This caused an outcry against the “White Australia” policy, spilling over to include the tour by Rev. Mick Waddy’s New South Wales team in 1913-14, the first dedicated tour of Sri Lanka by an Australian team. Two important cricketing brothers, Douglas and Eric de Saram, boycotted the series.

Returning to Australia, one of the cricketers, William Cameron, hinted at racial tensions:

“The colour, caste, or class line is, however, very sharply drawn. One or two members of the team ‘fell in’ rather badly over some indiscreet, or unguarded remarks at the expense of the ‘niggers’, as they termed them…”

Locals watching cricket at Galle Face, from H.W. Cave’s Book of Ceylon

Bodyline

Another hiatus occurred during the First World War, but international tours resumed in the 1920s. The Australian Ashes team’s visit in 1930 stands out, being the first played by Don Bradman outside Australia. He wrote later:

“The cricket enclosure was a pleasant surprise; it was an excellent ground, and a big

crowd turned out to paint a picture of many colours. The people were most enthusiastic, and they had infinitely more than a nodding acquaintance with the game… The standard of play was appreciably higher than I had expected.”

He complained of the awkwardness of the solar topee (Sinhala: gal thoppiya) he wore, considered de rigueur for European cricketers at the time. In a rain-interrupted match, Bradman was out, hit-wicket to Neil Joseph for 40, one of only two such dismissals in his career.

Two years later, Douglas Jardine visited Colombo with his England team on the famous “Bodyline” series against Australia. At the S.S.C. Grounds, W.T. Brindley, later Inspector General of Police, anchored All-Ceylon innings of 125 for 3, when the local team declared to allow the crowd of 10,000 see the visitors bat. Jardine did not use his “secret weapon”, the bowler Harold Larwood, although the latter did bat. The Nawab of Pataudi, who batted for three hours, top-scoring for England in the drawn game, with 62 out of 186 for 7, described it as the most interesting innings he had ever played.

The “Bodyline” team. Pataudi is third from the left and Larwood, third from the right, back row; Warner is extreme left, middle row; and Jardine, centre, front row. Image courtesy Wikipedia

Later that year, All-Ceylon embarked on their first unofficial test series against India, nearly winning the first game at Lahore in December. It was a fitting climax to a century of cricket and a half-century of international cricket, but it would be a further half-century before Sri Lanka received test status.