One of the top ten petroleum companies in the world, B.P., (formerly British Petroleum) receives a revenue of about US$ 200 billion every year, about 2½ times Sri Lanka’s Gross Domestic Product. B.P.’s local agents, Associated Motorways, have their headquarters at Colombo’s Union Place. Just 180 metres away, down Staples Street, on the site of a former forage mill, one may find a supermarket belonging to the Cargills chain, Sri Lanka’s largest modern retail operation and one of Sri Lanka’s leading blue chips.

BP Petrol Shed in Guildford, Connecticut, USA. Image courtesy Mike Mozart/Flickr

Cargills Food City supermarket in Kilinochchi. Image courtesy Cargills (Ceylon) PLC

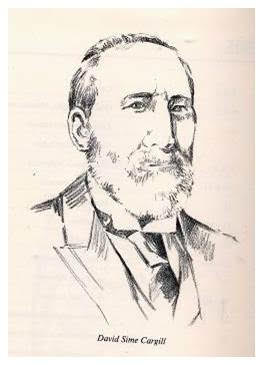

Although these two corporates are not connected today, at one time they were linked. The relationship existed through the person whose name is borne by the Sri Lankan retail group: David Sime Cargill.

David Sime Cargill, courtesy Cargills (Ceylon) PLC

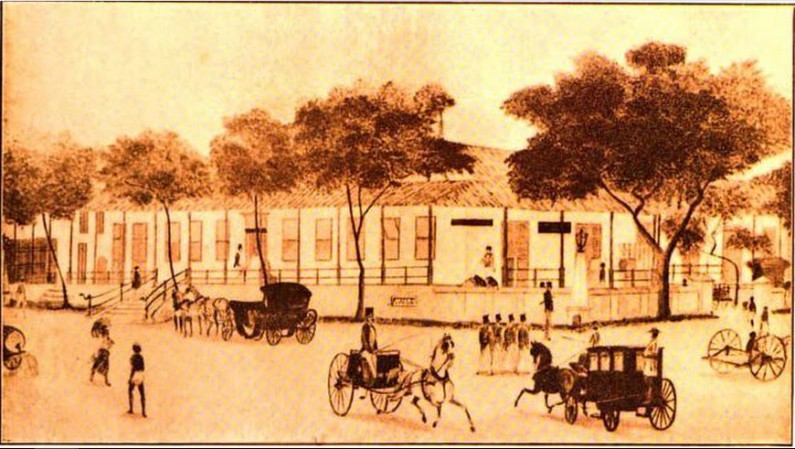

Milne & Co.

Born in 1827 in Maryton-by-Montrose in Scotland, 28km from Dundee, Cargill belonged to a moderately well-off farming family, owning 245 acres of farmland and employing six agricultural labourers. Leaving home at 15 to work in Glasgow, the young Cargill turned up in Colombo two years later. On 6 April 1844, he sailed aboard the ship Isabella Thompson, arriving in Colombo on 8 August.

The Ceylon Almanac and Compendium of Useful Information for 1846 mentions a “D. Cargell” living in Colombo in 1845. The next year, the Almanac places “D. S. Cargill” in Colombo, while the next informs us that he works for “Milne & Co” in Colombo.

This company, founded by William Milne on the very day that Cargill arrived in Colombo, operated as general warehousemen and importers of oilman stores (cheeses, hams, jams, pickles, preserves, salmon, sauces, tongues, vinegar, and so on). We know very little about Milne, a Glaswegian who first finds mention in the Ceylon Almanac in 1851, living in Slave Island and working at “Milne, Cargill & Co”. By that time, Cargill had gone into partnership with him.

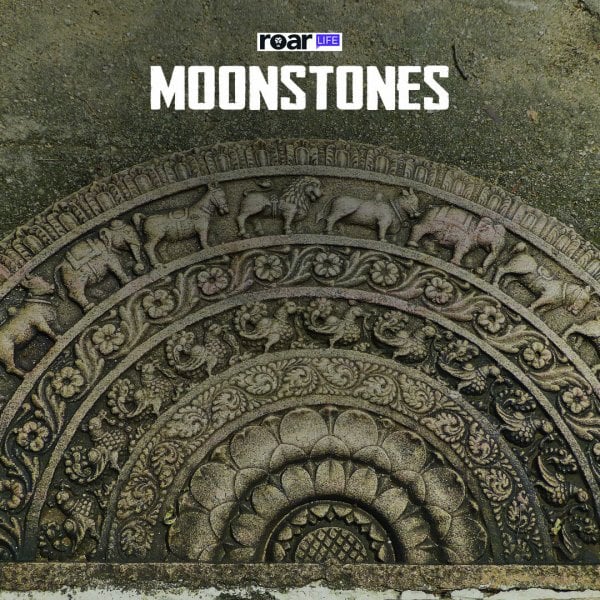

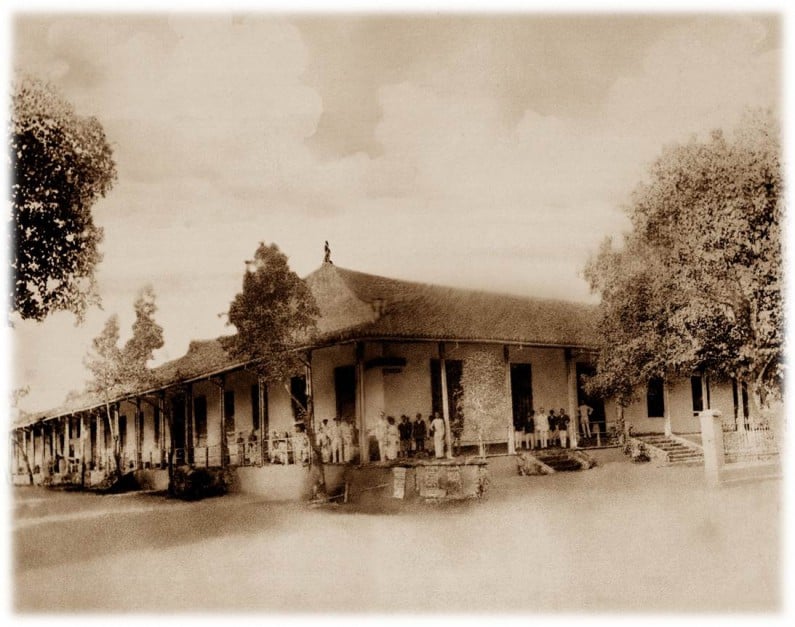

Peter Sluyskens’ House, from C. Brooke Elliot’s Real Ceylon, became Cargill’s shop

Milne, Cargill & Co

In 1851 Cargill returned to Scotland. On 30 March that year, we find him visiting Kenneth Macleay, a painter, and member of the Royal Scottish Academy. After he came back to Sri Lanka, his sisters, Helen and Grey Scott Cargill, joined him. Helen Cargill married William Mills Thompson of Templestowe Estate, Ambagamuwa, on 6 Sept 1855 at Colombo. They had a daughter, Dora Grey Thompson, who died on 18 March 1858, aged 17 months, at Alma Estate, Maturata, Sri Lanka. Grey Scott died at Alma two years later. Both lie buried at the Garrison Cemetery, Kandy, where Cargill erected a memorial.

Cargill bought Alma and Seaton estates in 1857. Over the next four years, he consolidated his holdings, paying the government about £2000 for a total of some 1,140 acres (460ha) in Hewaheta, according to records at the Sri Lanka National Archives.

The sum he paid, quite considerable in those days—equivalent to about Rs 45 million today, by one measure—makes it evident that the shop prospered. The coffee boom ensured plenty of liquidity for the British coffee planters, businesspeople, soldiers, and administrators of the colony. Homesick, they needed reminders of their life back home, and Milne, Cargill & Co provided them with the food items they would otherwise miss. The company now opened branches in Galle (at that time Sri Lanka’s major port) and Kandy.

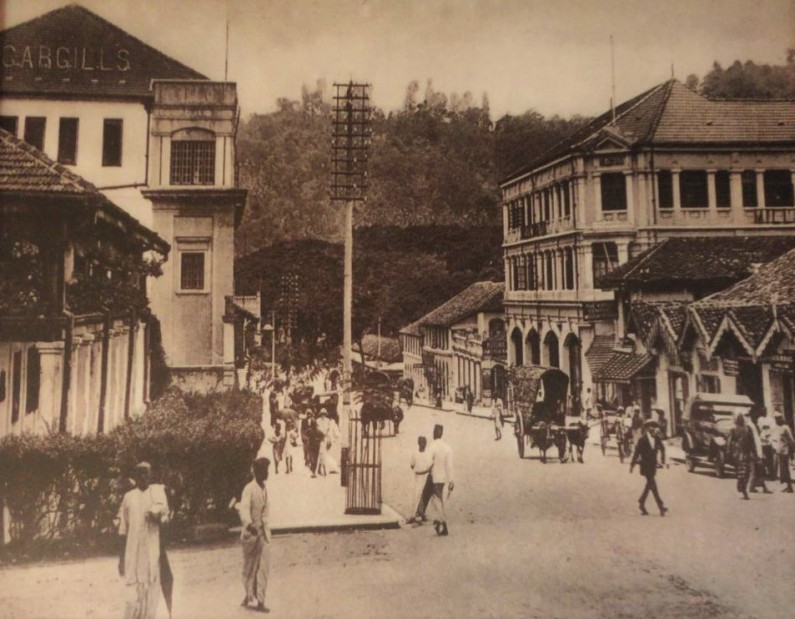

Ward Street, Kandy in the early 20th century, with Cargills’ sign prominent

Cargill & Co.

Cargill decided to return to Scotland. On 6 June 1861, he married Margaret Traill. Margaret’s father John Traill, a surgeon of Arbroath, had given evidence regarding children employed in factories, leading to the amelioration of their harsh situation. They had three sons and two daughters before Margaret died in 1872. In 1878 Cargill married Connel Elizabeth Auld, 19 years his junior, the daughter of William Auld, an accountant, and stockbroker, one of the founders of the Glasgow Stock Exchange and of modern accountancy in Scotland. They had a son and a daughter.

Moving from Arbroath to Glasgow, Cargill set up offices for Milne & Co, and later W. Milne & Co, East India merchants. The Colombo operation acted as agents for W. Milne & Co, along with several other companies, mainly banks and insurance companies, such as Scottish Commercial Insurance (in which Cargill received a directorship) and C. J. Hambro & Son (later Hambros Bank).

Back in Sri Lanka, Cargill handed Alma estate over to his brother-in-law Thompson and the management of Seaton and Terrace Hill to Cargill & Co, as the business was now called. Eventually, he and Thompson between them owned Alma, Ascot, Seaton, Greymount and Terrace Hill estates, totaling over 1,400 acres (570 ha). The retail operation he handed over to John Kydd, assisted by four European employees in Colombo and three in Kandy. It grew in size and stature, acquiring a pharmacy, opening a new branch in Nuwara Eliya and increasing the number of employees.

Cargill’s original building in the Fort. Image courtesy Cargills (Ceylon) Ltd.

Cargills Ltd

The company acquired a building fronting York Street, stretching from Baillie Street (now Mudalige Mawatha) to Prince Street (Baron Jayatilleka Mawatha), originally used for housing Dutch officials. When he first took up residence in Sri Lanka, Governor North had occupied the house on the corner of this block, belonging to the former Dutch commander of Galle, Pieter Sluyskens. This became Cargill’s department store and offices.

In 1890, an Australian visitor wrote that “Amongst the stores, Cargill and Co. is decidedly the most extensive, and there is no trouble in getting anything you require here from a needle to an anchor, or a bar of soap to a silk dress”, and referred to its “vast premises”. Cargills earned the epithet “the Harrods of the East”, after the World’s most famous London department store.

The company demolished the building and raised the present structure in 1902-1906. A foundation stone dated to 1684 and a statue of a Greek goddess, recovered from the old building, are still extant.

In 1896, Cargill incorporated Cargills Ltd. in Glasgow, to run the operation in Sri Lanka. Six years later, he retired, handing over his share in the “East India” businesses to his son John Traill Cargill.

Burmah Oil

A petroleum refinery existed at Yangon (then called “Rangoon” by the British) since 1858, processing crude from Yenangyaung, one of the most ancient petroleum mining areas in the world, up the Irrawaddy River. It got into trouble and so, in 1871 the Rangoon Oil Company floated shares to acquire it. Cargill bought some, and later, somewhat reluctantly, became a director. In 1876, the company failed, and the directors sent Cargill to Myanmar to retrieve the situation. There he met Kirkman Finlay, a Scot who had established, with Matthew Tarbett Fleming (yet another Scot), a trading company in Yangon, Finlay Fleming & Co.

Cargill bought the Rangoon Oil Company for £15,000 (about Rs 330 million today), appointing Finlay Fleming & Co as the managing agents, as well as agents for Milne & Co. Finlay and Fleming both became partners in Milne & Co, while Cargill joined their company in turn. Finlay named his daughter Vary Cargill after his partner, illustrating how close they became.

Since King Min Thibaw refused to remove traditional restrictions on the ownership and size of oil wells, the Rangoon Oil Company still experienced difficulties and continued to run at a loss—subsidised by Cargill. However, in 1885, following the Third Anglo-Burmese War, the British annexed upper Myanmar, where Yenangyaung lay, exiling Thibaw. In 1886 Cargill and his partners incorporated the Burmah Oil Company (“Burmah” being what the British called Myanmar at the time) in Glasgow, to exploit the reserves of the newly acquired lands. With an initial capital of less than £60,000, it commenced drilling in 1887 and produced just 12,000 tonnes of crude oil annually.

Yenangyaung oil field in 1910. Image courtesy Wikipedia

Anglo-Persian

Burmah Oil expanded steadily and pushed exploration vigorously. It began exploiting new finds at Yenangyat, near Bagan from 1891, and in 1901 began drilling at Chauk Field, which became its most important petroleum resource. In 1905, the Sri Lankan-born Admiral John Arbuthnot Fisher began changing the fuel for the Royal Navy’s ships from coal to oil and entered into a supply agreement with Burmah Oil. On that basis, Burmah built a 443 km-long oil pipeline, then the longest in the world, from Magway to a brand-new refinery at Thanlyin, near Yangon.

Meanwhile, William Knox D’Arcy, an Anglo-Australian lawyer who had made money in gold mining, negotiated an exclusive agreement with the Shah of Iran to drill for oil in exchange for 16% of future profits. When he started running out of money, the British government asked Burmah Oil to step in, fearing D’Arcy might sell his concession to a foreign company. In 1908, after years of fruitless drilling, and just as they were about to stop—a telegram had already been sent to the drillers—they struck oil. The next year, Burmah Oil formed a subsidiary to exploit Iranian oil resources, the Anglo-Persian Oil Company.

The company built the world’s biggest oil refinery at Abadan to process its Iranian crude oil. In 1913, Burmah Oil negotiated a deal with Winston Churchill, whereby Anglo-Persian would be given exclusive rights to supply the Royal Navy, in exchange for the British government buying 51% of Anglo-Persian stock. Anglo-Persian changed its name to Anglo-Iranian in 1935, and in 1954 to British Petroleum, although most recognised by its initials, B.P.

William Knox D’Arcy. Image courtesy Wikipedia

Epilogue

In 1928, Burmah Oil formed a consortium with Shell, Burmah-Shell, to refine and market petroleum in the Indian subcontinent. This company, nationalised in 1976, now goes by the moniker Bharat Petroleum (also B.P). In 1963, Myanmar nationalised all Burmah Oil holdings in the country. The company survived, and bought the British lubricant company Castrol in 1966. The new company, Burmah Castrol, was in turn bought by B.P. in 2000.

Cargills registered offices remained at Glasgow, but Sir Chittampalam Gardiner of Ceylon Theatres bought a controlling interest in 1946 and incorporated Cargills (Ceylon) Ltd in Sri Lanka. This company remains the flagship of the Cargills Group, which encompasses businesses ranging from banking to dairy products.

David Sime Cargill did not, of course, live to see any of this. He died on 25 May 1904, aged seventy-eight years at his country home in Carruth, Renfrewshire. He left £929,190, equivalent to about £92 million (Rs 19 billion) today, although in terms of economic power, it would be equivalent to over ten times as much: today he would be a billionaire. His remarkable life, from farmer’s son to head of an oil and trading empire, remains all the more extraordinary in that he founded not one but two of the world’s steadiest corporate institutions.