For the days following November 10, you can expect all your local media outlets to concentrate their energies on a single subject: the national budget. Expect experts to wax eloquent on whether the budget is good for the country’s growth, whether the amount allocated for certain ministries is justified, whether the taxes proposed are the last nail in the middle-class taxpayers’ coffers (or coffins), and whether such a thing as a hydrogen car exists commercially.

Expect to be assaulted with so much budget-related information that the very word “budget” will soon lose all its meaning. Without a bit of guidance, however, average citizens like us, whose only reference point to a budget would be a household budget at the most, coming to terms with the creature that is the national budget on our own is tough. It’s easy to get lost in the many words experts like to throw around, and the media only amplifies the confusing din. If you’ve always been curious about how budgets are compiled and how you ended up paying that ridiculous tax figure, read on.

The A – Z On National Budgets

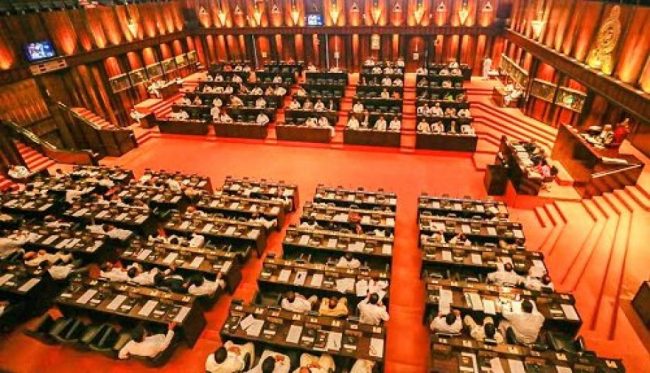

Finance Minister Ravi Karunanayake will deliver the 2017 Budget Speech in Parliament tomorrow (November 10). Image courtesy: lankabusinessonline.com

The budget, shortly put, underlines the Government’s fiscal policy, which would help sustain the country’s economic growth.

The responsibility of putting together the country’s budget rests, quite obviously, with the Ministry of Finance, under which specific departments like the Department of Fiscal Policy, the Department of National Budget and the Department of Public Finance work towards bringing it all together.

Something as vast as the national budget, however, requires coordination with practically every public institution, starting with the Central Bank. The Central Bank’s role is to provide the economic rationale, and this is presented in a report (submitted annually by September 15) which evaluates the budgetary performance and the economic conditions of the current year, the prospects for the next year, the overall rationale behind expenditure, the taxes that need revision, and taxes that need to be introduced or abolished.

According to ex-Central Banker W. A. Wijewardena, the government had in the past heavily relied on this report, and based much of the budget on it. However, of late, with the development of the technical capacity in the Ministry of Finance, the effective use of this report in the preparation of the budget has waned.

Although the budget is presented in Parliament in November every year, the work that goes into it starts in May, well before the presentation. The Department of National Budget, for instance, requests all ministries and statutory boards to submit their expenditure estimates by the end of July. The Department of Fiscal policy, meanwhile, contacts the country’s chief revenue generating agencies (namely the Department of Inland Revenue, the Customs Department and the Excise Department) who come up with their own estimates for expected revenue.

After the revenue and expenditure are consolidated, giving the Ministry of Finance a clearer idea of the total income and expenditure expected, the negotiations to cut down expenses begin. According to Wijewardena, most Ministries have adopted the neat trick of overestimating their expenses, and during the process of cutting down expenses, they essentially reach the amount they actually require. The results of this long drawn out negotiating process between the ministries and the Treasury finally culminates in the Appropriation Bill, which is presented by the Minister of Finance to Parliament a month before the final presentation.

The Appropriation Bill, together with government estimates, is essentially a detailed micro-level description of the budgetary outlook of the government, which is based on the operational inputs by the ministries, before a budgetary policy is arrived at. Independent to this, another report is prepared based on the economic and technical inputs as outlined in the Central Bank report (mentioned above). Essentially, therefore, the input for the budget comes from two different sources. Following discussions with the private sector, and factoring in their inputs, the final budget proposals are prepared.

Currently, according to Wijewardena, due to the Prime Minister’s keen interest in economic affairs, the budget has to be approved by the PM, too. The final budget is then presented to the Cabinet a day before the final presentation in Parliament, where amendments may be suggested. The impact of these suggestions is then evaluated by the Ministry of Finance and their feasibility is reported to the Minister, who re-consults with the Cabinet. Once the Cabinet approves of it, it is finally presented in Parliament and made public.

In Practice

After its presentation in Parliament, the Cabinet can suggest amendments to the National Budget. Image courtesy: srilankanewslive.com

There are, however, possibilities of errors passing through, as we witnessed last year, with the likes of healthcare and education. Wijewardena explained that while on the surface it looked as though the government was pumping in more money into education and healthcare (the allocation for education last year, for instance, was Rs. 189.97 billion, up from Rs. 47.6 billion for 2015), it was actually the result of erroneous calculations.

As frightening as that sounds, however, once the Appropriation Act is passed by Parliament, the Central Bank converts all the data to relevant functional classifications of government expenses as per the government financial statistics (which is an IMF manual allowing for a uniformity of classifications across the world).

What this essentially means is that what the Central Bank publishes in the Annual Report differs from what the Minister has presented in Parliament – and the figures presented in the Annual Report are the actual reflection of the expenses incurred by the government which directly affect, say, the students, as is the case with above mentioned example. The raw data presented in the budget, therefore, are*not* the actual expenditure in both functional and economic classifications as per the global practices relating to the government’s finance statistics.

To put this into context, when it comes to healthcare expenses, the Central Bank calculations are based on expenses that directly benefit the patients and help improve health standards. This includes the salaries of the doctors, nurses, public health inspectors, the cost of drugs and expenses involved in eradicating epidemics like dengue. The Central Bank pulls these expenses out from the detailed expenditure headings in the Appropriation Bill, recalculates and then presents this in their annual report in a table called the “functional classification of government expenditure.” This table essentially acts as the guide to the actual amount the government has spent on, say, healthcare. The only drawback, however, is that those seized by curiosity will have to hold their breath until the annual report is published by the Central Bank the following April.

Do’s and Don’ts

A major “don’t”, which the public should keep a keen eye out for, is the government retracting or backtracking after the budget has been approved by the Cabinet – any grievances should ideally be addressed at the Cabinet briefing and not after. If such an incident occurs, it is considered a violation of the collective responsibility of the cabinet, and results in a negative impression of the country in the eyes of the international community.

Such incidents have occurred in the past. For instance, in 1982, after for Finance Minister Ronnie De Mel presented the budget, a senior minister who criticised it in Parliament was asked to resign by the then president J. R. Jayewardene for violating the collective responsibility of the cabinet. If it has been approved by the cabinet, the decision cannot be reversed.

This does not apply to instances where an introduction has been made to the budget that was not approved by the cabinet. As Wijewardena put it, if such an instance occurs, it is up to the cabinet ministers to “be tough on the Finance Minister.” This hasn’t always been easy to put into practice, however, given the fact that since 1993 the Finance Minister of the country has also been President, as with President Wijethunga, President Kumaratunge, and President Rajapaksa.

If you have any concerns, there is unfortunately no actual mechanism for citizens to participate and pinpoint their grievances. On the other hand, trade unions, and other organised bodies, have been known to force the government on certain instances, and while it may benefit some, what it results in is an imbalance in the accounts. This may, in turn, harm another sector, highlighting how the political economy and the economic in general are at constant variance.

What you can do, however, as an informed observer of the circus, is to keep your ears tuned to the news – there may be things which the media, in their haste to report, or in keeping with political ties, may fail to report or highlight. Afterall, knowledge is power and knowledgeable citizens contribute to a better democracy.