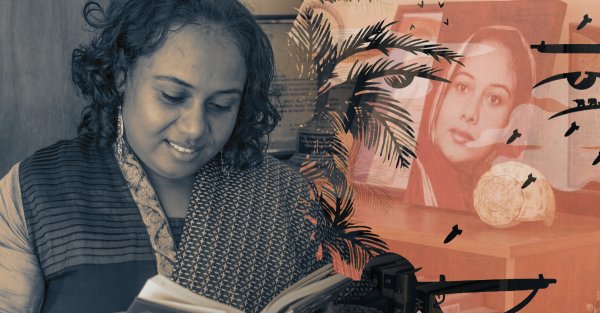

It sounds cliche, but when Hirunika Premachandra was 10 years old, she wrote an English essay about how she would like to be the President of Sri Lanka when she grew up.

“Everytime I watched the news, I saw this woman with a huge personality and charisma wearing an osariya,” she said of former President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga who was the first female president in the world. “ Watching her, in my little mind, I was thinking, ‘This is the easiest job in the world. You just have to go and dress nicely and stand in front of people.’”

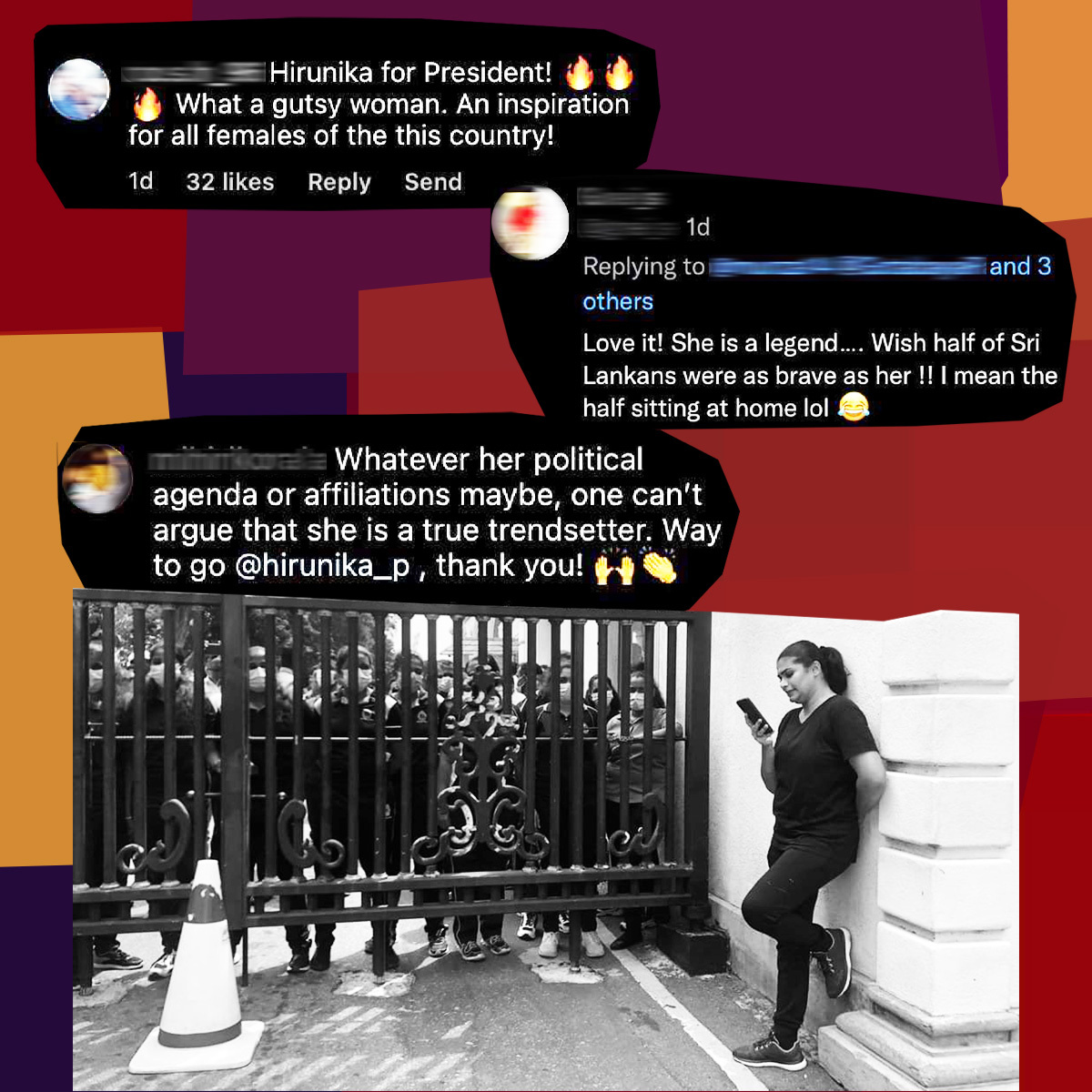

Premachandra has done both these things very publicly in the past months — she has dressed nicely and stood in front of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’ s house in Mirihana, in front of his soothsayer Gnana Akka’s shrine in Anuradhapura, in front of Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe’s house in Colombo 7, and mostly recently in front on President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s residence again — this time in Fort.

The internet both marvels at and mocks Premachandra. Even when she was arrested for protesting outside the President’s Fort residence two days ago, a photo of her standing alone in front of his gate with a crowd of security personnel behind it had already become a meme. “I find it funny,” she said. “Sometimes people can be rude, but they are mostly very talented.”

Premachandra speaks very strongly of accountability. “Even this house should be open to the public,” she said, referring to her own. “We live off public money, so there should be accountability. We [should be able to] go in front of any [politicians’] house, and demand answers.”

But as Sri Lanka enters its fifth month of sustained protests against the current president and his administration, Premachandra is as close to getting those answers as any of us are.

Boys’ Club, Man’s World

The night Premachandra’s father, former Sri Lanka Mahajana Party (SLMP) politician Baratha Lakshman Premachandra, died in 2011, someone leaked photos of her in a swimsuit from the Miss World Sri Lanka competition to the media.

A few months later, someone she will only identify as “a very well-known singer” spread a rumour that she performed a sexual act on the dance floor of a bar she worked at while at university. And on her wedding day in 2015, online media alleged she was three months pregnant at the time of the ceremony.

Just two weeks ago, photos of her cleavage exposed at a protest were all over the internet, with accompanying vile commentary.

“You see men without their shirts or their trousers, sometimes in their underwear, just running around, but you never see [anyone] taking pictures of that,” she said. “But because I’m a woman, my body is sexualised.”

Hirunika’s entry into politics occurred under trying circumstances. Her father was brutally gunned down during a shoot-out in 2011 led by former Member of Parliament Duminda Silva, who, despite having been found guilty of the murder in 2016, received a presidential pardon from Rajapaksa last year. The year after her father’s death, at the age of 24, Premachandra entered politics via the SLMP, vowing justice for her father’s murder. In 2014, she switched over to the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP), the same party as her late father, and quickly won over his former voter base. She received the highest number of votes at the provincial council elections for the western province that same year, and the following year joined the United National Party (UNP) through which she was elected to Parliament.

During the 2020 parliamentary elections, Premachandra, along with several other members of the UNP, broke away from the party to join the newly-formed Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB) under the current Leader of the Opposition, Sajith Premadasa.

Having worked with four separate parties over the course of only a decade, it is unsurprising that Premachandra has little regard for party politics. “I would say every party’s main focus is to get into power,” she said. “They all are so concerned about the party, they always forget about the country.”

She added that she thought this needed to change. “I think we need to come out of this mentality of party politics — it’s because of party politics that we are in this mess,” she said, explaining further that every political party was an assorted bag of people with genuine intention and potential but also those prone to rabid greed and corruption.

The voters must make the distinction, Premachandra asserted.

Manufacturing Image

Thus far, none of Premachandra’s perceived ‘scandals’ — the swimsuit photos and the exposed cleavage, for example — have been within her control to prevent from occuring. The former happened before she entered politics and the latter was the result of a physical confrontation with a policeman. Luckily for her, she has had the foresight to construct a public image that, if it hasn’t fully succeeded in countering the accusations levelled against her, have managed to contain them.

“I got into politics when I was 24. I’m 34 now. So at first I had to — even though I didn’t like it — I had to be cautious of what I did, what I wore,” she explained. “I had to grow my hair, so that I [could] put up a bun. I had to behave in a certain way. I couldn’t do what I really liked to do, and 24 is a very young age for that. And when I saw my friends doing what they did when they were 24, and when I had to just sit there like a grown-up woman, it was really upsetting for me.”

She explained that while she actually much preferred to wear T-shirts and jeans, public expectations had led her to adopt the more conventional sari.

But whether instinctively or by design, Premachandra has managed to reject the codes of conduct and value system associated with the ‘Sri Lankan mentality’ that expected her to dress and behave in a certain way while simultaneously pandering in some way to it.

She is also smart about the way she positions herself; the sari, the hair in a bun, the repeatedly associating and surrounding herself publicly with other women panders to one voter base, while the protesting, the telling-it-like-it-is, and the general defiance appeals to an entirely different one.

In the two hours we spoke, Hirunika alternated between associating herself first with motherhood and domesticity and next railing against how comfortably and impermeably sexism and misogyny are embedded in every aspect of Sri Lankan life.

It was clear to me that Premachandra represents a brand of women’s empowerment and an image of a female politician that pushes the boundaries in a way that is still palatable to most Sri Lankans; she has taken the path between compliance and confrontation, straddling the line between traditionalist and trailblazer.

On Politics

Her politics, too, seem to occupy a similar middle ground, despite the complexity surrounding her position. For instance, her views on politicians, the police, on protests only go as far as they can before her gender becomes the defining point she is forced to push back against. Adding to this is her own position as a beneficiary of the most commonly identified issues with Sri Lankan politics — nepotism, political dynasties, elitism. And there is also no proof that Premachandra’s views and policies — if she had the same complete freedom and ample leeway within which to express them as her male counterparts — would be any more progressive or radical than is typical for the centre-left SJB.

But although detractors are many, Premachandra is consistently better-received by the public than most other members of her party. Responses to politicians joining protests since they started in March this year have ranged from the openly hostile to the begrudgingly tolerant, but as a key figure in one of the earliest protests outside Rajapaksa’s Mirihana residence, Premachandra’s motives have rarely been questioned because she has made efforts to openly align herself with the people’s mandate, without attempting to co-opt the struggle or to dilute its message by positioning herself or her party as its solution.

“They don’t see a politician there, I believe,” she said of her joining protests. “My protest is authentic. I don’t believe a saviour can come and save us — good people who aren’t afraid of anybody have to come together.”

Aligning herself with the aims of the protests means that Premachandra, too, is in support not only of a change in governance itself, but a change in the system of governance and political culture that have brought us here, the system and culture that benefits even people like herself.

A repeated demand for reform from both the public and politicians is that future leadership be ‘intelligent’ or ‘educated’, but rarely do these demands acknowledge ethics or morality as a key metric with which to measure the suitability of a democratic leader.

“It’s not about how many books you’ve read or how many degrees you have,” Premachandra said. “It’s about good intentions.”

If her party is given the opportunity, whether as part of a coalition or by themselves, to form a government, Premchandra said she would like a position working with trade unions, like her father and grandparents.

“When a woman goes into politics, the public and the men think she should just take [the Ministry of] Women and Child Affairs and keep quiet and just sit somewhere,” she said. The very last thing Premachandra is likely to do is just sit somewhere.