“What glory, what majesty is Ravana’s, the Lord of Demons! Ravana is beaming like the sun with his rays difficult to be gazed, neither can the eye rest on him such is the binding strength of his magnificence!” —

K. M. K.Murthy, Valmiki Ramayana.

Ravana is the chief antagonist in the Indian epic Ramayana, written by the sage Valmiki, some time around 500 BC (although this is contested). This Sanskrit poem, containing nearly 24,000 verses, weaves the tale of Indian hero Rama, and his victory over the marauding King of Lanka, Ravana, who made off with his wife Sita.

But although Rama is positioned as the righteous victor in this epic, Ravana is viewed through different lenses on either side of the Palk Strait.

In India

In India, the Ramayana is held in reverence. Rama is believed to be the avatar of the god Vishnu, reincarnated to remedy evil in the world. He is depicted as the embodiment of all things good; the dutiful son who obeys his father, the faithful husband who fights for his wife, and the righteous king who accedes to the wishes of his subjects.

Sita is seen as the embodiments of all desired female qualities. She follows her husband into exile, remains faithful to him under duress, and uncomplainingly raises twin sons alone after she is expelled from the kingdom by Rama who questions her ‘purity’ after being abducted by Ravana. Hindus also believe she is an avatar of the goddess Lakshmi, the esteemed paragon of feminine virtues.

Temples such as the controversial Rama Janmabhoomi in Ayodhya, the Ram Mandir in Odisha, the Ramchaura Mandir in Bihar and the Sri Rama Temple in Kerala, are among many dedicated to Rama in India, while in the northern, southern and western states of India, the yearly festival of Dussehra celebrates the victory of Rama over Ravana.

Ravana, being king of the Rakshasa, is viewed as a demon. The Rakshasa are described as ‘man-eaters’, enormous and fierce with two fangs protruding from the top of the mouth. They have sharp, claw-like fingernails and are able to both fly and vanish. They are said to possess ‘maya’, the magical powers of illusion, which allowed them to change size and assume forms.

In Sri Lanka

Despite being a Rakshasa, Ravana is seen as different, and distinct, in that he is described as having ten heads, each attributed to varied aspects of physical and mental prowess. He is said to have been a great scholar, with an intimate knowledge of the Vedas (ancient Indian texts), and a master of aerodynamics, frequently using his flying chariot, the Pushpaka Vimana, in which he also spirited Sita away.

In Sri Lanka, Ravana is viewed as a powerful ancient king – claimed as a Sinhala icon by a group of nationalists – forced to avenge his sister. His character is held in high esteem, with writers drawing attention to the fact that Ravana did not force himself on Sita (i.e. rape her or forcibly marry her) while she was held captive, but only repeatedly asked her to marry him (N.B., Sita refuses).

This has been contrasted to Rama’s treatment of Sita, where despite the results of an agni pariksha (test of fire) to prove her purity, he is swayed by public opinion, and banishes a pregnant Sita to the forest. Sita gives birth to twin sons and lives with the sage Valmiki (who wrote the Ramayana) until he reunites her with Rama, but too late, as Sita calls on her mother, the goddess Bhoomi, to swallow her into the earth.

Educator Goolbai Gunasekara, who describes Ravana as a “gentleman”, and a “man of intellectual and scientific brilliance”, argues that “the real hero of the Ramayana is King Ravana of Sri Lanka”. This love for Ravana has also spawned a Sinhala-Buddhist supremacist movement—the Ravana Balaya, that has aggressively pursued its ideology at the expense of other ethnic and religious minorities in the country.

Inaccuracies

While Ravana is viewed alternately as hero and demon on either side of the Rama Setu, the narrow shoal of sand and rock that forms a bridge between Rameshwaram island in India and Mannar island in Sri Lanka (which, incidentally, is believed to have been built by the army of vanara, to rescue Sita), there are a number of inaccuracies linked to what people believe about this popular myth.

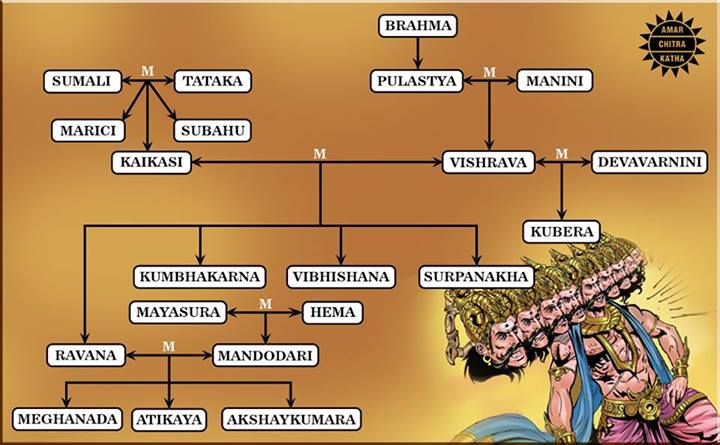

The most contentious among these is the idea that Ravana was Sri Lankan. As per the Ramayana, Ravana is described as being the son of the Hindu sage Vishrava. His paternal grandfather was the sage Pulastya, one of the ten ‘mind-born’ sons of the creator-God Brahma and one of the Seven Great Sages Rishi in the first Manvantara (a period of time measurement)—which would make Ravana distinctly Indian, not Sinhalese.

Even the historicity of ‘Lanka’ is disputed. The late Indian politician and writer, D. P. Mishra, pointed out that Sri Lanka was referred to as ‘Simhala’ in ancient Indian chronicles, not Lanka, and that the Lanka referenced to in the Ramayana was located in India (according to him, evidence pointed out that a stretch of islands on the Godavari River in Andhra Pradesh was the Lanka referred to in the epic).

Historian Romila Thapar has said that the matter has been disputed by Indian scholars for centuries and Lanka remains unidentified. Several other locations—Sumatra, the Maldives, Australia (via the Sunda Islands) and the Lingga Island, which is on the equator, have been suggested as alternatives to the theory that ‘Lanka’ refers to Sri Lanka.

In fact, Sri Lankan researcher and writer Hasitha Abeywardena drew attention to an observation by the late archaeologist Professor Senarath Paranavitana, who pointed out that there was no archeological evidence to corroborate the Ramayana. Even the Archeological Survey of India (ASI) has said there is no evidence to conclusively prove that Rama actually existed.

Identity

Professor Nira Wickremesinghe, a leading academic on South Asian studies, has pointed out in her book Sri Lanka in the Modern Age: A History of Contested Identities, that the ‘Hela’ theory promoted by scholars like Munidasa Kumaratunga, rejected the Vijayan ancestry of the Sinhalese, in favour of the theory corroborated by the Ramayana—that a great civilisations existed on the island before.

“It is a slur on the Helese nation to say that the arch robber Vijaya and his fiendish followers were its progenitors. Many thousand years before their arrival we had empires greater and mightier than the greatest and mightiest that any other nation could have claimed to have,” Wickremesinghe quoted Kumaratunga as having said, on the theory that Vijaya was the progenitor of the Sinhala race.

Wickremesinghe said proponents of Hela believed that the Hela kingdom was ruled by powerful monarchs such as Taraka and Ravana, who even challenged the military might of Indian empires, but said that the myth was embraced more as a need to “sharpen the boundaries, particularly with regard to India”—in particular, as a refusal to accept the Indian origin of the people of Sri Lanka.

She added, however, that the Hela theory of the origins of the Sinhalese and the earlier incarnations of the Ravana myth did not succeed in capturing the imagination of a large group of people, noting that “the Rama-Sita-Ravana myth which saw the king of Lanka ultimately defeated by Rama did not give Ravana a persona Sinhala people could easily identify with”.

While scholars, writers, researchers and lovers of literature and history continue to immerse themselves in the story of the Ramayana, and as the people of two countries across the ‘Rama setu’ continue to disagree in their opinions of the protagonists Rama and Ravana, it may be wise to discard the political underpinning of the tale and look only to the moral one.

What must be remembered is that the Ramayana, while cautioning against unchecked rage, desire, ego and evil intent that can cause the downfall of even a most powerful being, is at its heart, a simple celebration of the victory of dharma (righteousness, or things in keeping with the underlying cosmic order of things) over addharma (that which is not dharma, or right).

Cover: The Ramayana is a Hindu epic written around 500 BC. Image courtesy icytales.com

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this article referred to Ravana as a Sinhala king. This has now been corrected to reflect the fact that this is a claim made by some groups.