Since the late 1970s, outward migration has been crucial for the Sri Lankan economy, acting as a buffer against unemployment while attracting more foreign exchange — in the form of remittances — than most exports.

But the COVID-19 pandemic could change all that.

Media Spokesperson of the Sri Lanka Bureau of Foreign Employment (SLBFE) Mangala Randeniya told Roar Media that around 20,000 migrant workers across 14 countries have lost their jobs since the pandemic began, with many others experiencing drastic salary cuts.

He added that around 40,000 Sri Lankan citizens from 122 counties have been repatriated till October, with around 52,000 more awaiting repatriation. These estimates are conservative, due to the SLBFE’s limitations in gathering data.

Nonetheless, they suggest a range of economic implications, including disruptions in remittances, as well as the costs of repatriation and reintegration of workers into an economy where unemployment has risen due to COVID-19-induced shocks.

Remittances

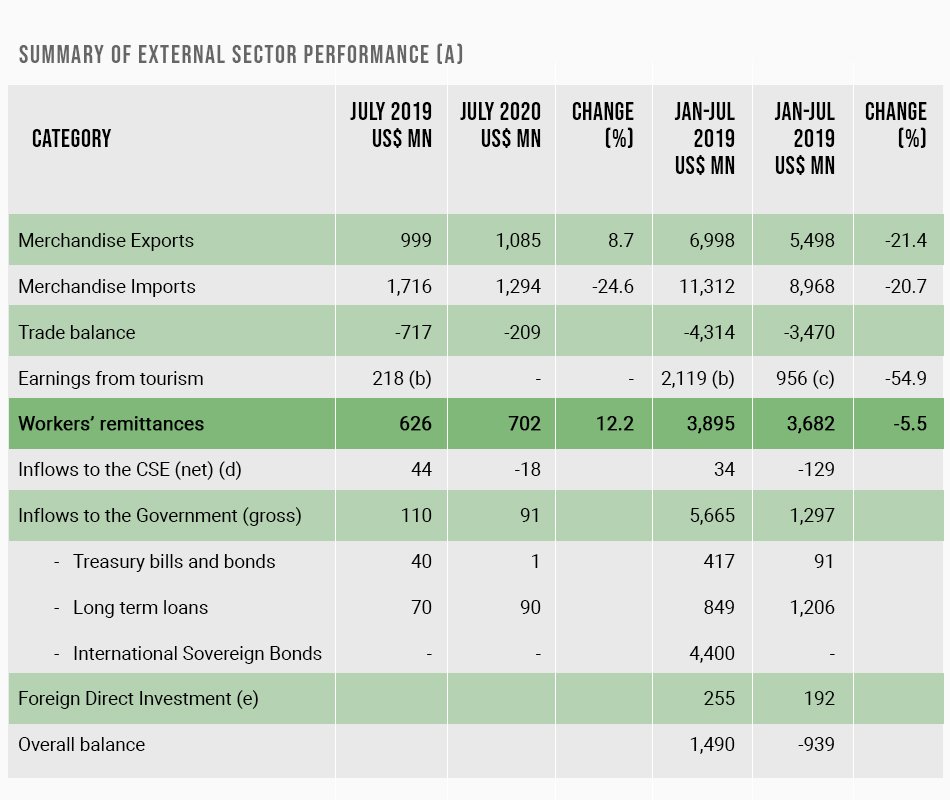

According to the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL), the country received USD 6.7 billion in worker remittances in 2019. For perspective, that figure was eight percent of GDP, 56 percent of export revenue, 33.6 percent of import expenditure, and 83.8 percent of the trade deficit for the year.

Surveys conducted by the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS), a think-tank established by an Act of Parliament in 1990, say that around 1 in 11 households receive remittances averaging LKR 40,000 per month per household.

A report published by the World Bank’s Migration and Remittances Team predicts that remittances to Sri Lanka will decline by nine percent in 2020. However, according to CBSL data, remittances from January to September have risen 6.7 percent compared to the same period last year.

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic saw remittances decline in the months of March, April and May. This may have been driven by lockdowns limiting migrant workers’ movement as well as redundancies, forcing workers to save rather than remit.

“When migrant workers return and new workers don’t depart, our total stock of migrant workers abroad reduces. That could directly hit our remittances and therefore our balance of payments,” IPS Research Fellow Bilesha Weeraratne told Roar Media.

In July, however, Sri Lanka recorded the largest remittances inflow since January 2018 and a 12.2 percent year-on-year increase. Remittances rose a further 28.2 percent in August, defying expectations from experts and government officials.

The rise in remittances, despite an anticipated drop amid repatriations, is still unexplained. One theory is that backed-up remittances from lockdown months were sent at once. A more worrying theory is that migrant workers could be moving their assets back to Sri Lanka as they permanently relocate.

Repatriation

Weeraratne pointed out that repatriation responsibilities are disproportionately borne by the country where the workers originate, because host countries are able to lay off migrant workers in the private sector while providing their own nationals stable employment in the public sector.

In this scenario, developing countries like Sri Lanka, which are already facing financial and infrastructure constraints amid the pandemic, have to find ways to provide basic food, shelter, quarantine, testing and affordable repatriation options for their migrant workers.

In March, the government of Kuwait offered migrant workers an amnesty for visa violations and paid options for repatriation. However, Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests were not carried out by the Kuwaiti government on the returning workers, despite requests from the Sri Lankan government.

Around a week after repatriation of migrant workers from Kuwait began, 219 cases of COVID-19 were detected among returnees. Repatriation was immediately halted due to limited capacity in hospitals and quarantine centres.

At the time, Admiral Prof. Jayanath Colombage told media that, “The availability of accommodation at quarantine facilities, the capacity of PCR tests and COVID-19 treatment facilities in the case returnees test positive for the virus, are the three main limitations that determine the number of Sri Lankans that can be repatriated daily.”

According to data from the National Operations Centre for the Prevention of COVID-19 Outbreak (NOCPCO), Sri Lanka has the capacity to quarantine about 10,250 people across 96 quarantine centres, and a hospital capacity of 1,552 beds across 12 facilities.

“Even though people shout to bring migrant workers back home, the reality is that we don’t have the capacity,” Coordinator of the Action Network for Migrant Workers (ACTFORM), Violet Perera told Roar Media.

Reintegration

Perera argued that another challenge with repatriation is the subsequent difficulty reintegrating these workers into a job market with few opportunities. Sri Lanka’s unemployment rose from 4.5 percent in the last quarter of 2019 to 5.7 percent in the first quarter of 2020.

“If migrants return home, the government has to formulate a proper skills-development and reintegration programme. In some cases, bringing them back home could be worse than simply helping them find employment in a third country,” Perera said.

Weeraratne noted that many migrant workers return home and invest in a small business. “They put their heart, soul and savings into it but after one or two years it goes bust because they don’t have the training or capacity to manage a business,” she said.

Planning Ahead

The COVID-19 pandemic, and the accompanying economic downturn, will eventually come to an end. And Weeraratne explained that Sri Lanka should be ready with a clear migrant worker policy to exploit new opportunities in the post-pandemic world.

“Upgrading the skills of our migrant workers would benefit Sri Lanka on a macro-level. For example, there is a huge market for care workers, but we also have to look at the domestic demand to see the trade-off there,” Weeraratne said.

“We have to be strategic and understand labour demand three or four years ahead in order to design training programmes.”

In 2018, around 55.17 percent of departing migrants were unskilled workers and housemaids, and over 79 percent travelled to countries in West Asia. The government’s National Policy Framework pledges to address these imbalances by promoting skilled, rather than unskilled, workers.

In August, State Minister of Foreign Employment Promotions and Market Diversification Piyankara Jayaratne said a five-year plan would be formulated for the SLBFE that would promote foriegn employment and keep digital records of migrant workers.

SLBFE Spokesperson Randeniya told Roar Media, “One of our main tasks is to raise national training standards to international levels, so that skilled workers can go to destinations like Romania, Poland, Israel, Singapore, Malaysia, Hong Kong, and Australia.”